Architecture is the practice of designing and constructing buildings and spaces to serve human needs. Architecture is both an art and a science, balancing the principles of physics and functionality with aesthetics and cultural symbolism. The origins of architecture trace back to the dawn of human civilization when people began constructing simple shelters using natural materials like stone, wood, and mud. Architectural practices and theories evolved in response to (and as a reflection of) cultural, religious, and technological advancements.

There are four broad classifications outlining how to describe architecture independent of individual styles: residential, commercial, public, and industrial.

- Residential architecture focuses on creating livable spaces for individuals and families. For example, European row houses balance comfort and functionality for large numbers of inhabitants within limited urban space.

- Commercial architecture creates spaces optimized for commerce. New York City’s Flatiron building is a prime example that makes innovative use of an unusually shaped plot of land to provide centrally located office space while creating a recognizable commercial identity.

- Public architecture curates communal spaces in service of public interest and identity. The Sydney Opera House is an iconic example of Australia’s modern identity and aspirations as a focal point for the arts.

- Industrial architecture focuses on structures that are purpose-built for manufacturing, production, shipping, and storage. The striking art deco Battersea Power Station in London is an example of industrial architecture that transcends its utilitarian goals to elevate the aesthetic of the city it serves.

Each type of architecture has unique priorities for its constructions. However, the broad focus of the discipline encompasses three sets of key characteristics. The first set concentrates on aesthetic elements of shape, line, color, texture, and light to create a cohesive visual experience. The second set focuses on the spatial and structural elements of scale, space, and movement, which determine the functional experience of a work of architecture. The third set of characteristics are the relational elements of symbolism and context, which shape how structures resonate with and reflect the identities of the communities they serve.

Architecture is of profound importance to both individual human psychology as well as societal well-being. Works of architecture not only provide physical shelter and security, but reinforce cultural identity through symbolism of form, scale, and ornamentation. Architecture provides both the impetus and means for communal activity, fostering a sense of belonging and permanence among its patrons. Furthermore, well-designed spaces facilitate positive social and professional interactions, making them a crucial component of daily human experiences.

The intentional construction of dwellings and spaces predates the etymology of the word “architecture”. However, the term derives from the concept of an individual or group who assumes responsibility for planning and executing purpose-built structures. Evidence of this clearly defined role exists in the ancient Greek architektōn, which roughly translates to mean “master builder”.

Indeed, an architect must possess mastery of a broad range of skills in order to effectively manage the complexity of a given construction project. Chief among these skills is an aptitude for conceptualization and problem-solving. The larger functional and symbolic goals of an architectural undertaking must be grounded in reality, so it is incumbent upon the architect to consider how these aims will be achieved in actionable phases. Attention to detail is thus paramount in the field of architecture to ensure the efficiency and safety of the project and end result alike. Good architects tend to be perpetually curious about the latest technical aspects and cultural contexts of their ideas and collaborate with their peers to develop innovative solutions.

Famous architects throughout history have demonstrated the rigorous intellectual qualities outlined above. For example, Imhotep of 2600 BCE Egypt is widely regarded by historians as a polymathic priest, writer, and physician in addition to his attribution as the world’s first recorded formal architect. Similarly, the 1st-century Roman architect Vitruvius demonstrated a systematic approach to architecture with his treatise “De Architectura”, in which he defined the Classical building principles and methods that would profoundly inspire later architects. Chief among these was the Italian humanist Leon Battista Alberti, who authored the seminal Renaissance architectural treatise “De Re Aedificatoria” in 1452. This work reformulated and expanded upon Classical ideals, systematizing the practical and theoretical aspects of architecture according to principles of human-centered design.

Visionary architects of later periods such as the 19th-century French pedagogue Étienne-Louis Boullée would further develop the standard of architecture as an intellectual pursuit. Boullée’s utopian designs embodied the most aspirational Enlightenment ideals of philosophy and society at large. Architectural thought continued to evolve into the 20th century, exemplified by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. His “organic architecture” concept revealed the potential for human habitation to exist in harmony with its natural environment and proved pivotal within the broader socio-cultural discourse of modern architecture. Wright’s European contemporary, the Swiss architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris “Le Corbusier” pursued a similar equilibrium between architecture and humanity itself. Le Corbusier viewed houses as “machines for living in”, prioritizing human dignity and happiness as their main function.

What is the origin of architecture?

The origin of architecture is evident in prehistoric man-made structures from the Lower Paleolithic era. The earliest known evidence of architecture is the Terra Amata site which dates back to 400,000 BCE. The site is located on Mount Boron near Nice, France, and was discovered in 1966 by French archeologist Henry de Lumley. De Lumley theorized that the site comprised a community of animal-skin huts, departing from the caves in which early humans took shelter. De Lumely and his team additionally found evidence of manmade fires and Paleolithic tools, further suggesting that prehistoric humans occupied the area in a long- or short-term capacity. That said, the origins of architecture potentially began much earlier than the Terra Amata. The 2010 publication, 21st Century Anthropology: A Reference Handbook by H. James Birx, discusses the theory that early humans built tree houses or nests earlier than 400,000 BCE similar to modern-day apes such as chimpanzees or orangutans. These nests or tree houses would be basic forms of architecture, built for sleeping and security. However, little evidence exists to support this idea as organic material used to create tree-bound structures would have decayed quickly. As a result, the French site of Terra Amata remains the earliest sign of architecture in human history.

The concept of architecture expanded during the Neolithic period to a closer contemporary understanding of complex engineering. Humans during the Neolithic stopped living in caves and began domesticating plants and animals. This led to growing communities that required long-term structures that could withstand the elements, house resources, and provide spaces to sleep and cook food. Architecture consequently became necessary to human survival and later expressions of religion and spirituality. The oldest known permanent settlement from the Neolithic period is Göbekli Tepe in Turkey. Göbekli Tepe was erected in 9500 BCE and housed people until 8000 BCE when it was abandoned. The site served both a practical purpose of shelter as well as a religious function. Decorative elements such as animal reliefs suggest spiritual symbology, highlighting one of the earliest examples of aesthetics in architecture. Göbekli Tepe therefore indicates that aesthetics became a part of architecture as early as 9500 BCE.

Aesthetics likely became a part of manmade structures because they express and evoke human experiences and emotions, as captured by the decorative and spiritual elements of Göbekli Tepe. Aesthetics became more elaborate and significant as architecture developed throughout antiquity and human engineering advanced to facilitate larger projects. For instance, the execution of architecture was paramount to the development of Mesopotamian civilizations as they required infrastructure to not only house large populations but to articulate religious or royal importance. Megastructures like Mesopotamian ziggurats were a feat of ancient human ingenuity as well as an example of religious fervor as they functioned as places of worship. Later civilizations in antiquity continued this trend, combining function with architectural aesthetics and symbolism to develop cities and culturally significant structures. The Ancient Egyptian civilization is an example of this as they erected cities and built notable sites like the Giza Pyramid complex and the Step Pyramid of Djoser to house their growing populations and deify their leaders. The latter example, the Pyramid of Djoser, was built by a deified figure and the first-named architect in history, the physician Imhotep.

Imhotep is significant as few architects in antiquity were ever named because architecture was indistinguishable from stone masonry and carpentry. Moreover, architecture was a collaborative effort, and rulers are typically credited with commissioning a structure. The origin of architecture as a career did not emerge until as late as the 18th century wherein an occupational separation was necessary to develop greater feats of engineering and design. The origins of architecture as a concept and as an occupation have since expanded to compensate for the exponential growth of humanity across centuries. Architecture continues to function as a practical necessity by which humans have warmth and shelter, as well as a professional endeavor to evoke human emotion and artistic expression through the architect’s creative mission. Modern architecture is consequently a diverse field that poses distinct challenges, opportunities, and even myths that are unique to the art of building design.

There are three myths associated with architecture. Firstly, the idea that excellent drawing skills are necessary to be an architect is a common myth. Architects indeed utilize their artistic senses to design a structure, but the purpose of drawing in architecture is more functional than creative as architects need to logically communicate their ideas to others. Furthermore, architects rely on other skills beyond drawing, such as math, networking, and collaboration to complete their projects. Secondly, it’s a myth that architects work alone. Architecture was historically a collaborative effort of stonemasons and carpenters. This trend continues today as architects typically work in teams alongside engineers, contractors, and clients to develop projects. Finally, it’s a common myth that architecture focuses solely on aesthetics. Architecture is oftentimes artistic and expressive, with designers seeking to convey a specific message or idea through a structure. However, architecture largely prioritizes function over aesthetics as the way humans are able to interact, navigate, and experience a building affects the success of a structure more than its visual experience does.

What is the etymology of the word Architecture?

The etymology of the word “architecture” has its roots in the Greek word ἀρχιτέκτων or architéktōn. Architéktōn breaks down into two parts archi (start, govern, lead) and tékton (builder, mason), which together roughly translate to “chief builder”. The Latin word architectus derives from the Greek, and has a similar meaning of “architect”. Architectus shares a root with the Latin architectura, providing the etymological stem for modern translations like the Spanish arquitectura, the German Architektur, and the French architecture. The Anglo-Saxons lacked a specific word for architecture prior to the 1066 Norman invasion, so the English word “architecture” is a direct loanword from the French language.

What are the historical eras of architecture?

Below is a list of the historical eras of architecture.

- Paleolithic (400,000 BCE to 10,000 BCE): The Paleolithic era is a prehistoric period where humans did not live in homes or advanced shelters but most likely in nests, huts, and rock shelters. The earliest evidence of a manmade structure is the Terra Amata where archaeologists theorize a beach-side community lived in huts made of animal skin and built domesticated fires. No known architects exist from this era as it predates the written language.

- Neolithic (10,000 BCE to 2,000 BCE): The Neolithic era marks the beginning of more advanced approaches to architecture as humans transitioned from living in rock shelters and began domesticating plants and animals. A notable structure from this era is the Göbekli Tepe site which was erected in 9500 BCE and likely served both a functional and religious purpose. Basic structures of rock, mud, and megaliths additionally characterize Neolithic architecture.

- Mesopotamia (10,000 BCE to 600 BCE): The Mesopotamia historical era groups the architectural efforts of major civilizations who lived in the region of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, such as the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians. Mesopotamia marks the beginning of major architectural efforts and the development of urban planning. Reliefs, mud bricks, mosaics, and ziggurats characterize this era. One of the most notable buildings from this period is the Ziggurat of Ur which was constructed in 2050 BC by King Ur-Nammu of the Neo-Sumerian Empire as a place of worship.

- Ancient Egypt (3100 BCE to 395 CE): Ancient Egyptian structures are one of the most significant examples of architecture in antiquity due to the advanced engineering and projects that took place. Ancient Egyptian architecture is broadly characterized by architectural elements such as symmetry, symbolism, limestone, papyrus-styled columns, and astronomical alignment. One of the most notable landmarks, the Great Pyramid of Giza, represents these fundamental elements. Additionally, ancient Egypt gave rise to the first named architect in history, the defied physician Imhoptep, who allegedly designed the Pyramid of Djoser in the 27th century BCE.

- Mesoamerica (2000 BCE to 1519 CE): Ancient Mesoamerican architecture encompasses major civilizations such as the Olmec, Mayan, Aztec, and Zapotec peoples. The civilizations bore distinct architectural features according to their region and culture, but we’re able to generalize ancient Mesoamerica through the stepped structures, corbelled arches, flat roots, and mythological iconography that characterize Mesoamerican infrastructure. No records exist of named architects, but Mesoamerica gave rise to many notable structures such as the Pyramid of the Sun and the Moon which were built by the Teotihuacan civilization between 100 AD and 450 AD.

- Classical architecture (700 BCE to 400 CE): Classical architecture groups the structural characteristics of ancient Greece and Rome. Ancient Greek is characterized by the Greek column orders of Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian as well as symmetry and usage of the golden ratio. Two notable architects from Ancient Greece include Ictinus and Callicrates who built the Parthenon. Meanwhile, ancient Roman architecture was influenced by Ancient Greece and was governed by columns, arches, as well as domes, and more advanced developments of aqueducts. A well-known ancient Roman structure is the Colosseum which exemplifies notable qualities of Roman architecture. Another famous architectural example is the Forum, an open-air plaza built by architect Apollodorus of Damascus.

- Byzantine (330 to 1453): The Byzantine time period corresponds to the architecture of the Byzantine Empire, otherwise known as the Eastern Roman Empire. Domes, mosaics, monumental scale, and religious symbolism characterize the era. Byzantine structures additionally took inspiration but gradually became more distinct from Roman architecture. One of the most famous structures from Byzantine is the Hagia Sophia, a church-turned-mosque that was designed by architects Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. The Hagia Sophia exemplifies the peak of Byzantine engineering as well as the time period’s emphasis on grand interiors.

- Romanesque (1050 to 1170 ): Romanesque architecture marks the transition away from broader architectural eras that corresponded to a single region or civilization. Romanesque architecture existed across medieval Europe and is associated with elements like decorative arches, small windows, piers, and towers, as well as barrel, groin, and ribbed vaults. Few named architects are accredited with constructing buildings during this period, though noteworthy structures like the Abbey Church of Saint Foy and the Basilica of Saint-Sernin represent fundamental elements of the time period.

- Gothic (1150 to 1600): The historical era of Gothic architecture corresponds to the High and Late Middle Ages of Europe which emphasized Christian symbolism. Gothic architecture consequently corresponds to religious iconography as well as fundamental features like stained glass windows, monumental scale, flying buttresses, and vertical lines. One of the most famous structures from the time period is the Notre Dame de Paris, which serves as the hallmark of French Gothic architecture, capturing the major architectural elements. The St. Vitus Cathedral is another notable building. It was built by Peter Parler, a famed Gothic architect and descendant of a family of master builders.

- Renaissance (1400 to 1600): The Renaissance era was a European movement spurred by technological and artistic innovation that adapted classical architecture. Consequently, Renaissance architecture is characterized by prominent classical elements, such as symmetry, columns, and domes, as well as heightened religious inspiration, advanced geometry, exaggerated proportions, and the integration of sculpture as an aesthetic quality. The Renaissance period additionally gave rise to many notable architects, including Filippo Brunelleschi, Donato Bramante, and Michelangelo. These architects were responsible for famous structures like St. Peter’s Basilica, which was a collaborative effort of Vatican City’s best artisans.

- Baroque (1600 to 1750): Elaborate and vivacious interiors, ornate details, extensive usage of shadows, large domes, gilded sculptures, and curved shapes characterize the Baroque era of architecture. Baroque succeeded the Renaissance and consequently influenced Europe as a whole, giving rise to opulent structures such as the Palace of Versailles in France and the Karlskirche church in Vienna, Austria. The period is additionally marked by skilled architects who helped guide the movement, including Gian Lorenzo Bernini who defined the Baroque sculptural style, and Louis Le Vau, who was the court architect of Louis XIV of France and worked on the garden of the Palace of Versailles.

- Neoclassical (1750 CE to 1920 CE): The Neoclassical style originates from France and Italy, but it transcended borders and influenced architecture across Europe and Northern America. Neoclassical is additionally one of several architectural eras that took inspiration from Greek and Roman structures, demonstrating simplified forms, minimal details, and symmetrical exteriors. Neoclassical architecture departed from late Baroque opulence to create grand but visually balanced structures such as the Panthéon by architect Jacques-Germain Soufflot or the United States Capitol building by William Thornton. Both buildings convey a sense of order in addition to distinct Greek and Roman architectural elements.

- Victorian (1837 CE to 1901 CE): The Victorian era refers to the architectural style that became predominant during the reign of Queen Victoria of England. The era is distinguished by key characteristics such as steep roofs, iron railings, asymmetrical exteriors, decorative trims, and stained glass windows. Victorian architecture ranges from bright palettes to dark color schemes. Two prominent examples of the historical era include the Painted Ladies of San Francisco and the Carson Mansion in Eureka, California. The latter was designed by the architects Samuel and Joseph Cather Newsom, prominent American architects who contributed to the Victorian movement stateside.

- Art Nouveau (1883 to 1914): The historical era of Art Nouveau was distinguished by a shift toward organic forms, including curved lines and floral or plant-like motifs and decals. Stained glass windows and abstract aesthetics additionally became prominent. The movement began in France and Belgium but spread across Europe and the United States of America. Notable structures inspired by the era include the Casa Batlló, an Art Nouveau building that emphasized natural shapes and whimsical details. The building was developed by Antoni Gaudí, one of the most famous architects in history and designer of the Sagrada Família, another Art Nouveau structure that combines classical Gothic elements to create a unique blend of grandeur and opulence.

- Art Deco (1919 to 1939): Art Deco architecture is characterized by stark geometric shapes, accentuated lines, ambitious feats of engineering such as skyscrapers, and luxurious materials previously unused or underutilized. The structures erected during this period additionally reflected the growing consumerism and industrial pursuits of the United States. Art Deco skyscrapers such as the Empire State Building by the Shreve, Lamb & Harmon firm, and the Chrysler Building by William Van Alen feature sleek lines and decorative elements quintessential to the movement. The skyscrapers additionally embody the era’s focus on modernity and architectural ambition through the innovative usage of steel that gives the buildings their iconic exteriors.

- Modernism (1917 to 1965): Modernism was a historical era of architecture governed by minimalism, flat roots, neutral color palettes, glass, steel, and reinforced concrete. Modernism marked the end of more luxurious and expressive styles such as Art Deco. The era influenced architecture across the Western world, leading to the development of notable structures such as the Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, as well as Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright. These buildings exemplify the departure of ornamentation and the era’s emphasis on functional spaces and simplified forms.

- Postmodernism (1950 to 2007): Postmodernism developed to oppose the minimalism of modernism, employing brighter color palettes and organic shapes while maintaining much of the geometrics of the previous era. The result was experimental designs that emphasized the architect’s artistic vision over functionality. Two examples of postmodern structures include the Portland Building by Michael Graves and the firm, Emery Roth & Sons, as well as the SIS Building by Terry Farrell and Partners. These structures represent the eclectic designs of the era by featuring a mixture of historical references and ornamentation while maintaining the basic geometric elements of modernism.

- Contemporary (2000 and beyond): Contemporary architecture corresponds to present-day architectural movements. Consequently, contemporary architecture is diverse and includes styles such as parametricism, brutalism, deconstructivism, neo-modernism, neo-futurism, and sustainable structures. Additionally, contemporary architecture tends to be governed by experimentalism with notable architects such as Frank Gehry and Norman Foster exploring unconventional forms and shapes in their work. Examples of contemporary buildings include the Copenhagen Opera House in Denmark and the One World Trade Center in New York City, United States. The former illustrates neo-futuristic elements whereas the latter is an example of contemporary modernism.

What are the types of architecture?

The types of architecture are defined and exemplified by the list of twenty-one major architectural styles below.

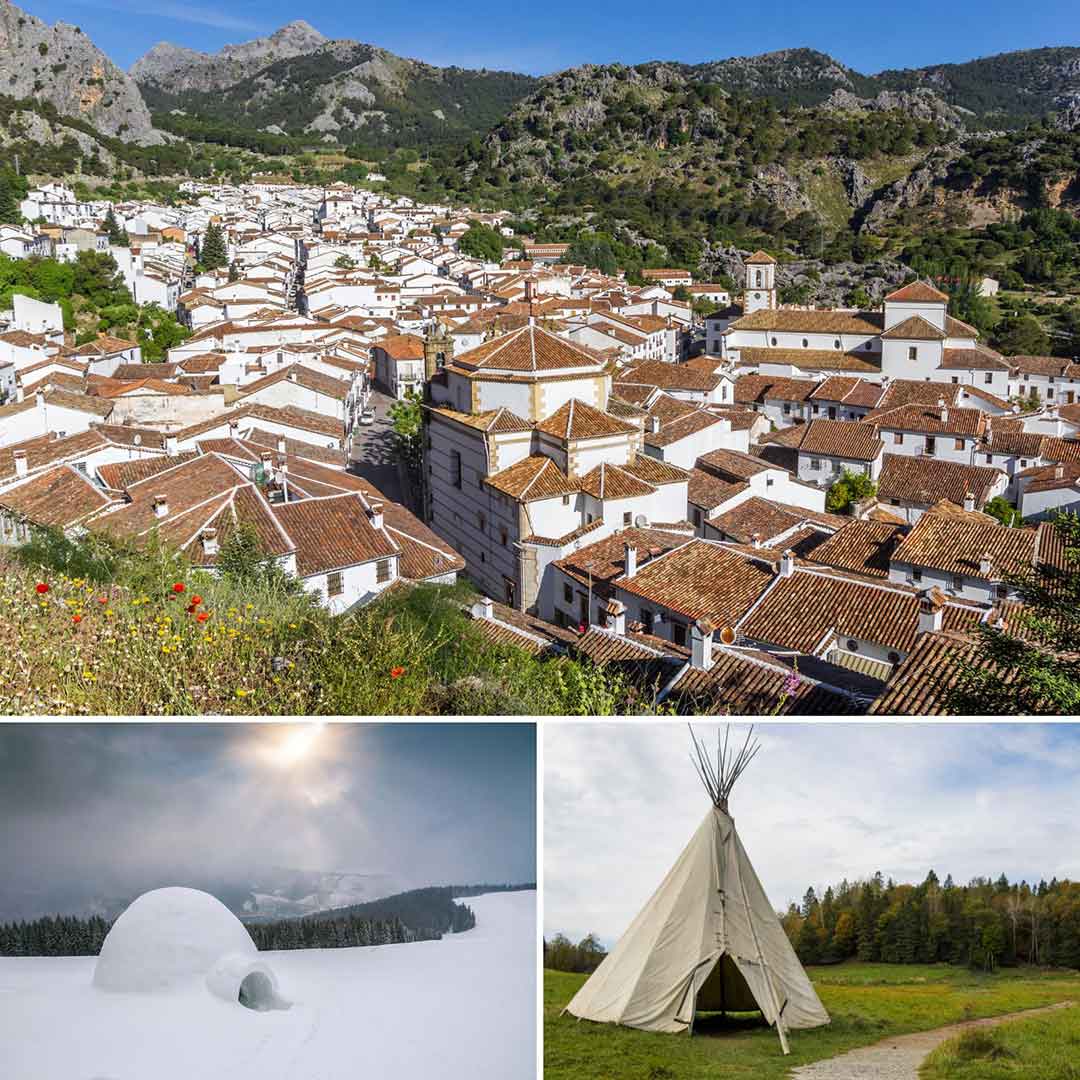

- Vernacular architecture: Vernacular architecture is ubiquitous throughout world history, and reflects the environmental and cultural needs of the people it houses. Inuit igloos are exemplary of the idiosyncracies of form that such shelters can demand, making use of widely available resources to protect against the harsh arctic environment.

- Classical architecture: The Classical period of architecture emerged in ancient Greece in the 5th century BCE and endured through the Roman Empire. The style’s seminal architect is Vitruvius, whose foundational work “De Architectura” formalized Classical architectural precepts of balance, symmetry, and proportion.

- Gothic architecture: The emergence of the Gothic style in early 12th-century France is widely attributed to Abbot Suger’s ambitious renovation of the choir of the Abbey of Saint-Denis. His use of ribbed vaulting and pointed arches pioneered the characteristic ribbed vaulting and pointed arches that would define later Gothic works such as the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris.

- Renaissance architecture: Renaissance architects pursued a return to Classical ideals, elevating platonic notions of form with an updated understanding of depth and symbolism. Michelangelo’s dome on St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican exemplifies the technological advancements and cultural prominence characteristic of Renaissance architecture throughout 14th-16th century Europe.

- Baroque architecture: Baroque architecture is a late 16th-century reaction to Renaissance restraint that embraced ornamental opulence in order to foster an emotional reaction. The Italian artist and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini designed the colonnade of the Piazza San Pietro to represent the “Maternal arms of the mother church” in characteristically Baroque recognizance of the viewer’s role in defining the form and function of architectural works.

- Modern architecture: Modern architecture marked a departure from historical styles beginning in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, focusing on function over form and showcasing new materials like steel and concrete. Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye in France exemplifies the movement with its streamlined design and the application of his five points of architecture.

- Postmodern architecture: Postmodernism emerged in the 1960s as a reaction to the perceived sterility of modern architecture, reintroducing ornamentation and historical references. Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s AT&T Building (now known as 550 Madison Avenue) in New York, with its Chippendale-inspired top, is a hallmark of the style’s playful engagement with history.

- Deconstructivist architecture: Deconstructivism is characterized by fragmented forms and manipulated structures. Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, with its seemingly chaotic metallic curves, embodies this novel 1980s architectural approach.

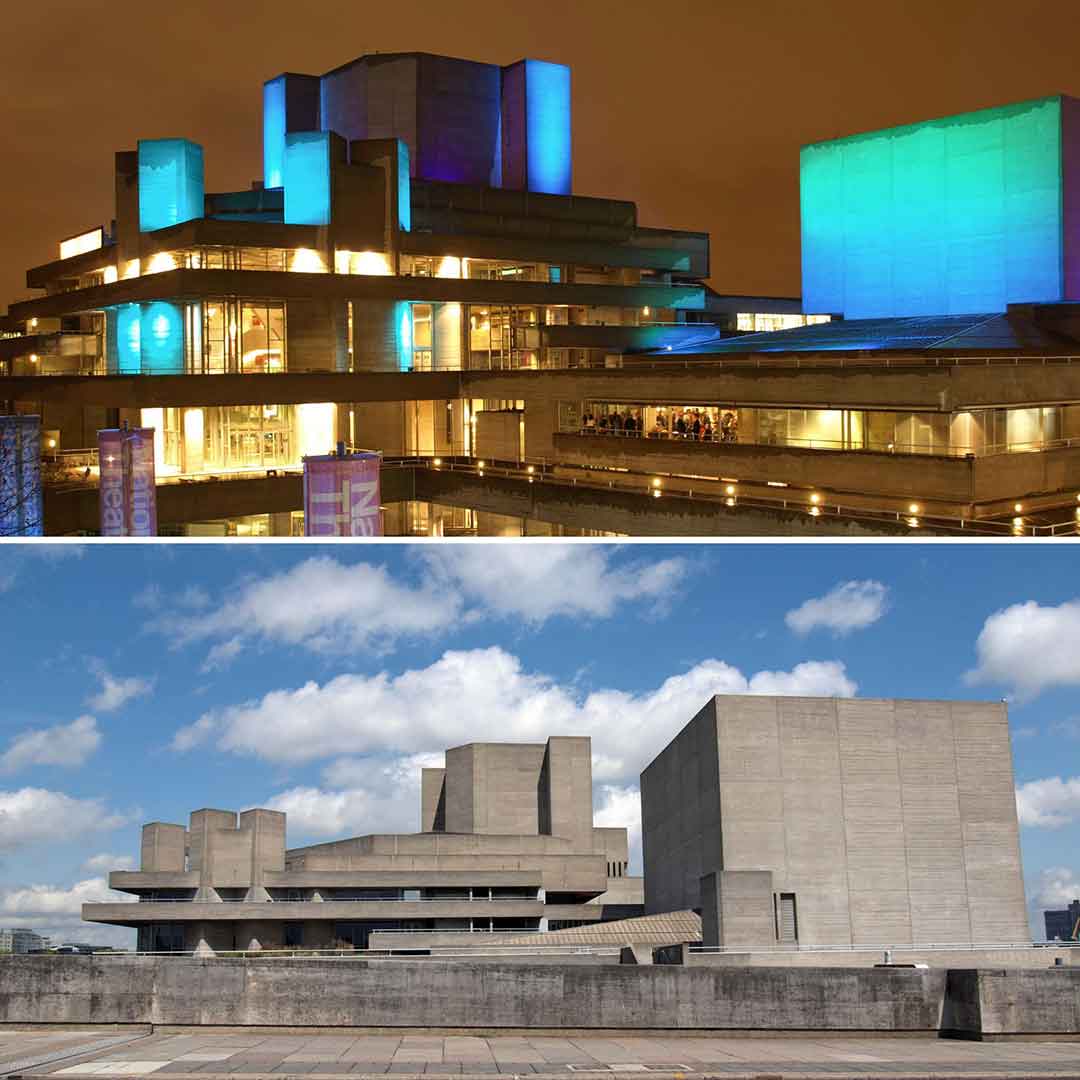

- Brutalist architecture: Brutalism is a mid-20th-century architectural style known for its raw, unadorned concrete structures. Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille represents the style with its emphasis on utilitarian function and repetition of form.

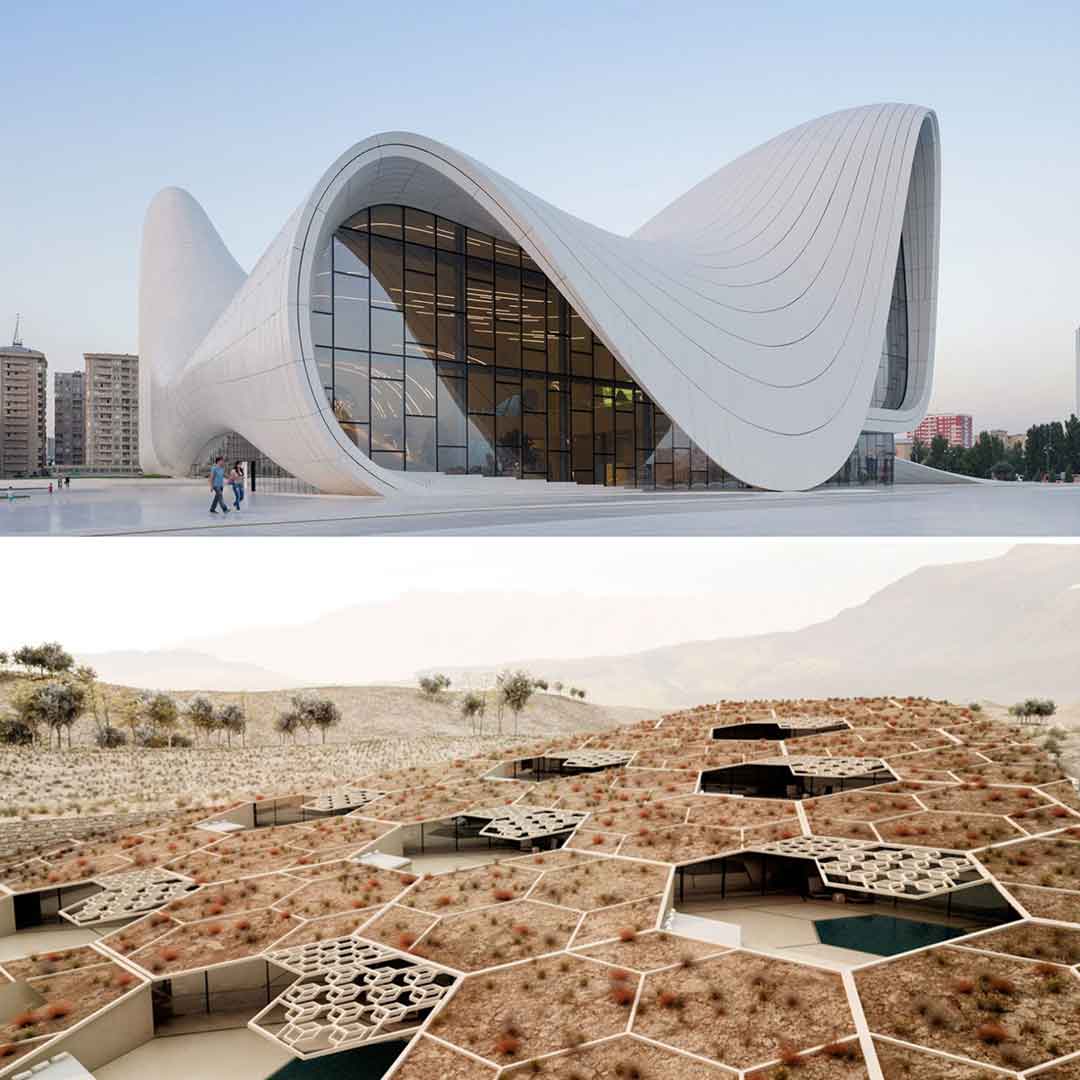

- Parametric architecture: Parametric design utilizes computer algorithms to produce buildings with complex curves and patterns. Zaha Hadid’s Heydar Aliyev Center in Azerbaijan typifies the fluid forms possible through this 21st-century digital approach.

- Residential architecture: Residential architecture caters to private living spaces adapted to cultural and individual needs spanning human history. Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1939 opus Fallingwater in Pennsylvania epitomizes the seamless integration of residence with its surrounding environment.

- Commercial architecture: This modern style emphasizes brand identity due to its focus on commerce and business. The Apple Store on Fifth Avenue in New York, with its innovative glass cube entrance, represents the blend of function and brand recognition.

- Industrial architecture: Architectural design focused on industry conceptualizes large spaces that use functional materials to create a productive environment for manufacturing, storage, and shipping. The Van Nelle Factory in Rotterdam, Netherlands, exemplifies the functional aesthetics of early 20th-century industrial design.

- Institutional architecture: This ubiquitous mode of architecture is tailored for accessibility in establishments like schools and hospitals. Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium in Finland is a prime example that prioritizes patient well-being in its design.

- Landscape architecture: This discipline specializes in designing outdoor environments by harmonizing ecological, cultural, and social needs. Frederick Law Olmsted’s design for Central Park in New York, completed in the 1870s, stands as a paragon, merging natural landscapes with urban amenities to provide a multifunctional public space that caters to diverse recreational and communal activities.

- Interior architecture: Interior architecture concentrates on the design of interior spaces with functionality and aesthetics. Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Willow Tea Rooms in Glasgow, showcasing early 20th-century Art Nouveau design, stands as a testament.

- Sustainable architecture: his approach emphasizes ecological responsibility and efficient resource use in design and construction. Renzo Piano’s Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre in New Caledonia showcases this philosophy, employing local materials and passive design techniques to reduce energy consumption, all while celebrating the region’s indigenous Kanak culture.

- Power architecture: Power architecture is designed to project authority and power through large-scale, enduring, culturally salient constructions. The Pentagon in Virginia, built during World War II as the Department of Defense’s headquarters, embodies this concept through its massive scale and imposing structured form.

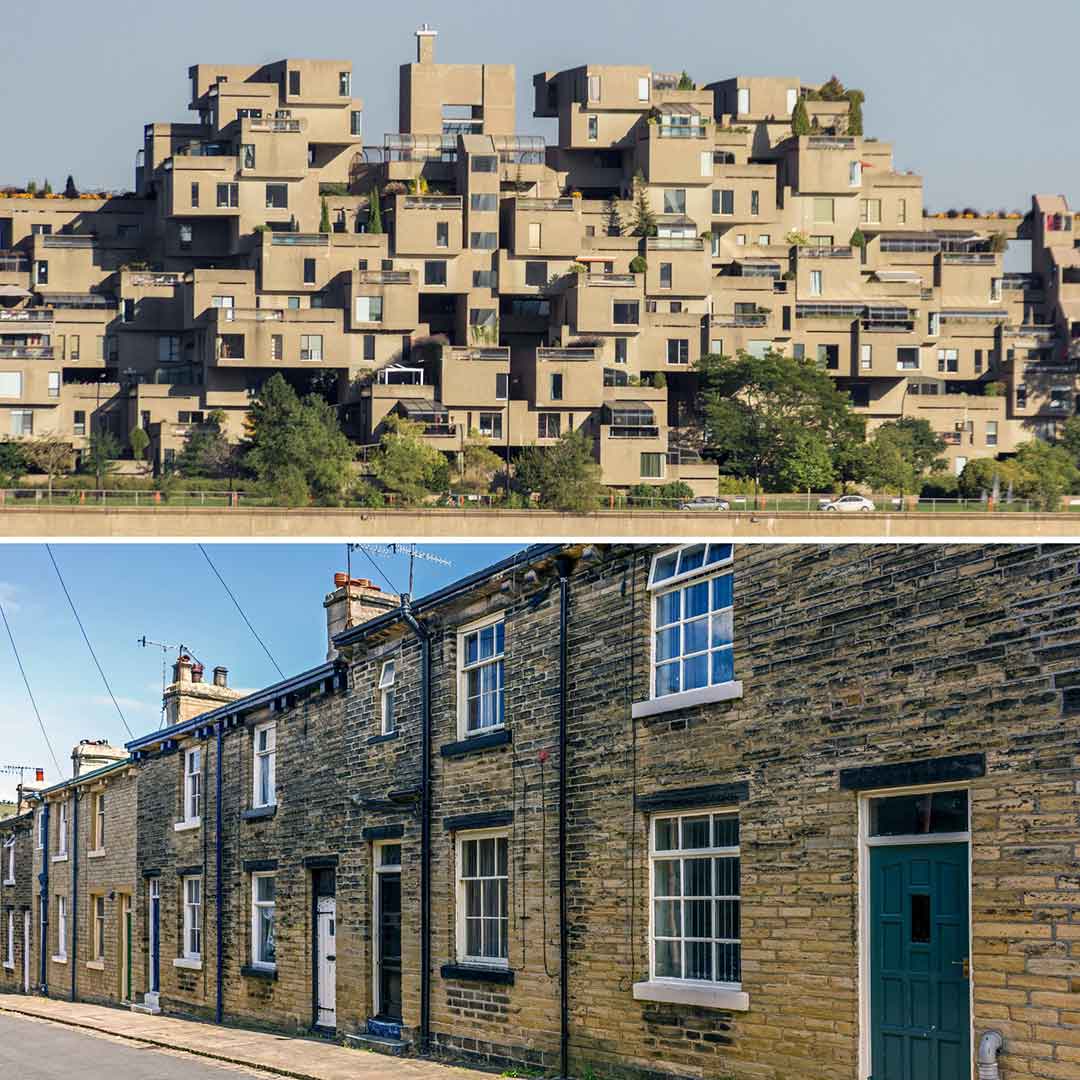

- Group housing architecture: The goal of group housing architecture is to optimize shared spaces in order to foster community actions while preserving resources. Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 in Montreal is emblematic of this style, with its interconnected concrete boxes offering both private and communal spaces in a radical reimagining of urban living solutions.

- Religious architecture: Religious architecture evolved over millennia and serves as a testament to mankind’s diverse spiritual expressions and preoccupations. The Sagrada Família in Barcelona, designed by Antoni Gaudí in 1882, encapsulates this with its intricate facades and towers that marry Gothic and Art Nouveau forms in homage to Christian motifs.

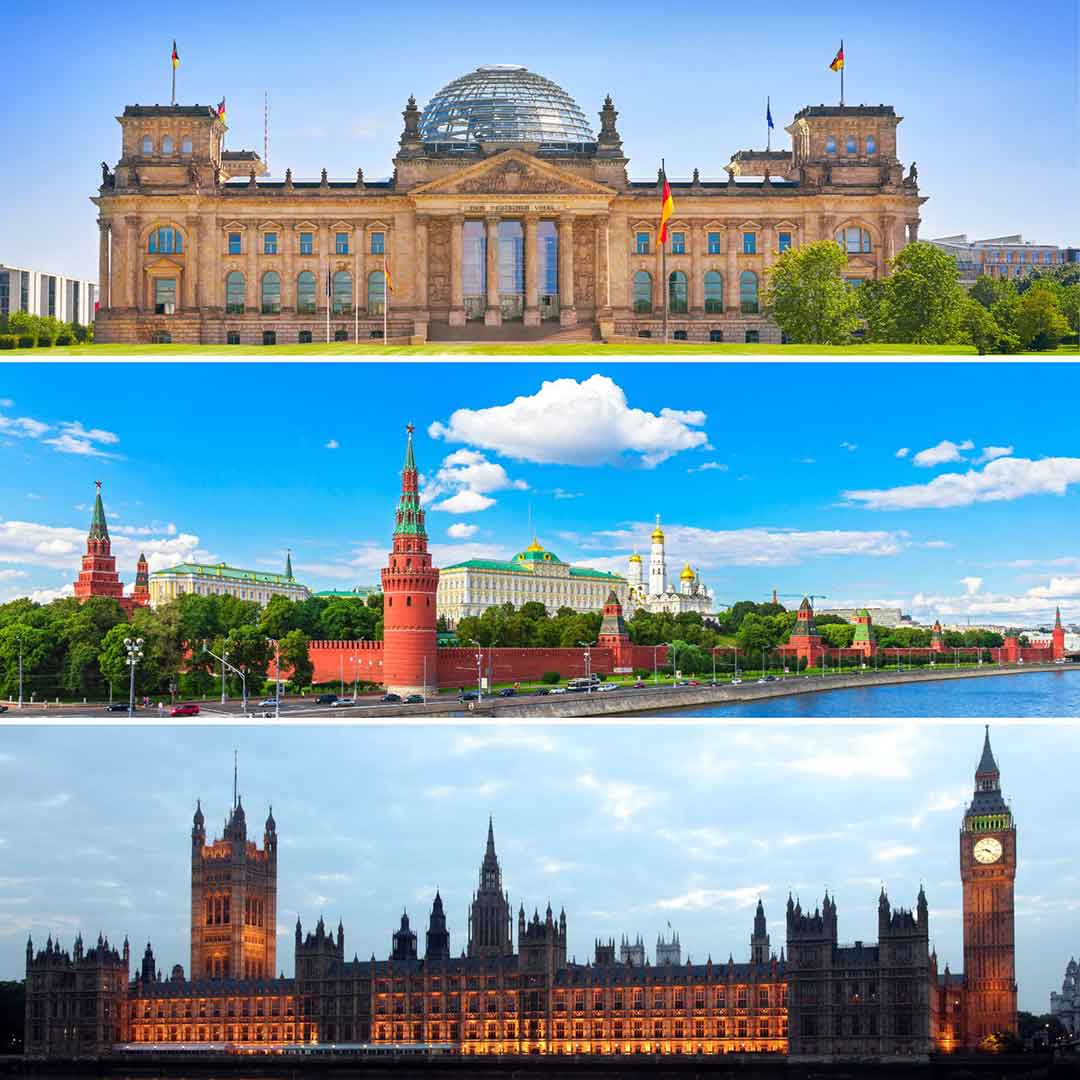

- Governmental architecture: These structures symbolize state power and civic functions. Sir Edwin Lutyens’ design of the Rashtrapati Bhavan (Presidential Residence) in New Delhi embodies this, melding traditional Indian and British architectural elements, representing the colonial era and its influences on India’s urban fabric.

The above is not an exhaustive list of all possible architectural styles, modes, and classifications. Other important and influential styles contribute to the broader architectural discourse, namely Romanesque, Expressionist, Organic, Tropical, and Futurist architecture. However, for the sake of brevity and clarity, we focus on the 21 most widely impactful types of architecture in greater detail below.

1. Vernacular architecture

Vernacular architecture is a traditional, pragmatic approach to building human habitation that predates any formal school of architecture. Vernacular architecture essentially exists to serve specific cultural or environmental needs and typically makes use of materials that are locally abundant. Examples of vernacular architecture are as varied as the cultures they represent and abound from the dawn of civilization up through the preindustrial era. The pueblos blancos of Andalusia bear a distinctive slaked lime whitewashing that not only serves as natural cooling amidst intense Spanish summers but stands testament to the ingenuity of Moorish architects who made use of this material’s disinfectant properties to combat the spread of cholera. Similarly, the native Inuit built igloos from locally harvested icebrick to retain heat amidst the harsh arctic climate. Vernacular architecture is of profound historical importance, as it provides intimate insights into the traditions, values, means, and contexts of a given culture.

Virtually every nation on earth has some tradition of vernacular architecture, however, every example tends to share three general characteristics. First, vernacular buildings make use of readily available materials. Pre-industrial civilizations tended to use natural materials, however more modern examples of vernacular architecture like East German plattenbauten feature economically advantageous resources like concrete. Second, vernacular architecture provides specific environmental advantages. The thatched-roof houses of the British Isles, for example, offer substantial waterproofing and resilience against heavy wind. Finally, buildings in the vernacular style tend to reflect the cultural traditions of their builders. For example, the rumah gadang of West Sumatra features a curved roof resembling water buffalo horns, an allusion to the Minangkabau legend from which the native inhabitants derive their name.

2. Classical architecture

Classical architecture is a building style rooted in the traditions and principles of ancient Greece and Rome, emphasizing balance, symmetry, and proportion of form. There are three main orders within Classical architecture that serve as design templates constraining a building’s proportions, details, and decorative elements. The first and oldest order is Doric, characterized by fluted columns that sit directly on the floor without a base–usually present within Greek temples. The second order is Ionic, wherein more slender columns stand on a base and are topped with a scrolled design called a volute. The third and most ornate order is Corinthian, which retained the slender Ionic column design but further adorned the tops with acanthus leaves. The most famous example of classical architecture is the Parthenon in Athens, Greece, which was built in the 5th century BCE as a monument to the goddess Athena and featured Doric columns and elegant pediment sculptures.

Classical architecture’s importance to Western architecture is immense because it provided a platonic conceptual basis for form and function. Later styles of architecture used Classical precepts as a frame of reference, whether in reaction (like Gothic or Baroque) or in revival (like Renaissance and Neoclassical). Classical architecture dates back to the 7th century BCE in ancient Greece but remains a relevant cultural touchstone and point of study for modern architecture. Modern Western buildings such as the US Supreme Court in Washington DC and the British Museum Reading Room in London reflect classical influences with their domed roofs, columnar construction, and extensive use of marble and stone.

3. Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is a style originating in Medieval Europe primarily used in the design of religious buildings like Christian cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture makes intentional use of high-rising features designed to direct the viewer’s gaze up towards the heavens. There are three main characteristics that constitute Gothic’s aspirational nature. The first characteristic is the enhanced structural support afforded by ribbed vaults, flying buttresses, and pointed arches, which allow Gothic buildings to reach towering heights without overly thick walls. Second are the characteristic stone grotesques, which functioned as waterspouts by also served as a symbolic reminder of the dangers of secularism. The third main characteristic is large stained glass windows, which depict religious iconography and allow light to fill the upper vaults with heavenly light.

The most famous example of Gothic architecture is the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, France. The cathedral’s intricately sculpted doorways, circular rose windows, slender vertical lines, as well as its gargoyles and chimeras all exemplify both early and High Gothic styling typical of the 12th century. Gothic architecture spread beyond France throughout Europe as an expression of cultural identity, religious piety, scholarship, and artistic sophistication. The Gothic stylings of many buildings within the campuses of Oxford and Cambridge stand as a testament to the formative ties between academia and the church.

4. Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture represents a revival of Classical principles like proportion, symmetry, and balance. However, Renaissance architects were less constrained by technological building limitations or strict adherence to Classical orders than their historical influences. The dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City is the most famous example of a Renaissance evolution in Classical architecture. Three primary characteristics separate Michelangelo’s masterpiece from its Greco-Roman predecessors. First is the sheer size and height of the dome; although it is of a similar diameter to the Roman Pantheon, its innovative double-shell construction allows it to rise to far greater heights without compromising integrity. Second, Renaissance buildings were more ambitious with their decorative elements, as evidenced by the Basilica’s intricate ribs. Third, Renaissance architects often made use of Classical elements to heighten the symbolic importance of their works; Michelangelo designed the Basilica’s dome lantern as a shining beacon of Christendom.

Renaissance architecture spread from 14th-century Italy widely throughout Europe into the early 1600s. Its influence brought a profound shift in cultural values away from medievalism and into the Enlightenment era. The movement’s renewed focus on Classical principles encouraged the standardization of architectural practice, laying the groundwork for the profession as it is understood today. One of the most influential Renaissance treatises was Leon Battista Alberti’s 15th-century work “De Re Aedificatoria”, a collection of 10 books providing instruction for urban planning, material usage, as well as theoretical and practical aspects of architecture derived from ancient Rome.

5. Baroque architecture

Baroque architecture is a highly ornate style of late 16th-century European architecture that emerged as a reaction to the platonic simplicity of Renaissance architecture. There are three primary characteristics that convey the Baroque period’s evocative impetus. Firstly, Baroque architecture makes ample use of opulent ornamentation such as gold leaf, shell motifs, garlands, drapery, cherubs, and vivid frescoes in order to evoke a sense of splendor. Second, Baroque structures undulate and curve in a dynamic way to create the illusion of movement and energy. The third characteristic is the express intention to make an emotional impact on the viewer, especially in religious contexts to bolster the preeminence of the Church. The Church of Sant’Agnese in Agone in Rome is emblematic of the Baroque style with its dynamic facades, sculpted vaults, and a dome that gives the illusion of floating amidst light-filled windows.

The legacy of the Baroque period is in how it intermixed artistic disciplines. Architects of the day worked hand-in-hand with sculptors and artists to create a holistic transcendental experience. Moreover, the push for decadence prompted profound experimentation with the spatial precepts revived by Renaissance thinkers, further establishing architecture not only as a profession but as an art form unto itself. Baroque architecture represents an evolution of human-centric enlightenment values in how it foregrounded the human experience of a given work.

6. Modern architecture

Modern architecture is an architectural style that utilizes clean lines and minimalist design to emphasize functionality over ornamentalism. The modern architecture, or modernist, movement began in the late 19th century with a revolution in building and design techniques and continued into the 20th century. For example, modernist architecture capitalized on a combination of newer materials and technologies, such as cast iron, drywall, plate glass, and reinforced concrete, to push the limits of architecture and create unique sturdy buildings. The Palácio do Planalto in Brazil, designed by Oscar Niemeyer, exhibits key features of modern architecture. For example, the Palácio do Planalto boasts white marble columns that support a flat concrete roof with vertical glass surrounding the façade. The modernist design is an important historical advancement in architecture because it embraced revolutionary building techniques and offered a solution to growing urban spaces.

Modern architecture has three main characteristics. Firstly, modern architecture follows functionality over ornamental designs. The Villa Savoye in Poissy, France, designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, is a textbook example of modern architecture’s focus on minimalism and function. The Villa Savoye features a floor plan devoid of load-bearing walls, which allows for flexibility in wall placement and a free-flowing layout. Secondly, modern architecture is characteristically innovative with traditional building materials. Fallingwater is a modern architectural design in Stewart Township, Pennsylvania, by Frank Lloyd Wright that exemplifies the innovative qualities that define modern architecture. Fallingwater’s modern design utilizes stone, concrete, steel, glass, and wood to create an organic aesthetic that blends into the natural waterfall and surroundings of the home. Thirdly, modern architecture is characterized by integrating with nature. The Farnsworth House by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in Plano, Illinois, showcases the harmony between modern architecture and nature through 360-degree views of the surrounding floodplain. The clean parallel lines of the house flow with the nearby river, and the interior views allow for a near-total submersion into the natural setting beyond the tall glass windows.

7. Postmodern architecture

Postmodern architecture is an architectural style that diverges from the strict rationality of modernism to incorporate playful, eclectic, and ironic elements. Postmodern architecture emerged in the later half of the 20th century as a response to the perceived emptiness and lack of liveliness in modernist architecture. The theme of postmodernism is to have visually appealing and playful structures that stray from minimalist design. Postmodern architects aimed to communicate with users and visitors through a mix of historical elements and eclectically using new materials. For example, the SIS Building in London, designed as the headquarters for the British Secret Intelligence Service by Terry Farrell and Partners, breaks away from the stark modernist box and features symmetrical curvatures and a mix of concrete and glass plateaus. The SIS building’s complex design resembles ancient Babylonian ziggurats, which earned it the nicknames of the Ziggurat and Babylon-on-Thames. Postmodern architecture is historically important because it challenges the norms of architectural thinking and reintroduces ornamentalism, humor, and cultural connection to design.

Postmodern architecture has three defining characteristics. Firstly, modern architecture includes a mix of historic and contemporary motifs that exude whimsy. 550 Madison Avenue in New York City, designed by Philip Johnson and John Burgee, encapsulates the blending of styles and whimsical design with its Chippendale-inspired broken pediment, an ornate gesture atop an otherwise modern skyscraper. Secondly, postmodern architecture prioritizes symbolism and design over pure function. Piazza D’Italia in New Orleans, designed by Charles Moore, showcases classical elements like columns and arches, but in an abstract and fragmented manner. Thirdly, postmodern architecture is colorful and incorporates varying textures. The Portland Building in Portland, Oregon, designed by Michael Graves, exemplifies the vibrancy of postmodern architecture with blue tiles and salmon-pink stucco. The mixture of colors and materials brings the structure to life amongst the backdrop of otherwise modern and commercial buildings.

8. Deconstructive architecture

Deconstructive architecture is a style of architecture that uses distorted lines, angles, and planes to manipulate the structure’s continuity. Deconstructive architecture emphasizes asymmetry and features a single material to construct large spaces. The emergence of deconstructive architecture took place in the late 20th century and lasted until the early 21st century. For example, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao constructed in 1997 by Frank Gehry, showcases the deconstructive architectural features of fragmented design constructed from titanium that bends in varying directions. The sense of unpredictability and controlled chaos in the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao challenges the norm of architecture and emphasizes the evolving urban environment. Deconstructive architecture is an important contribution to architectural history because it encourages architects to question the accepted conventions and embrace ambiguity. Deconstructivism brought a new way of perceiving and interacting with spaces to the forefront of design by breaking the rules of traditional architecture.

Three main characteristics encapsulate deconstructive architecture. Firstly, deconstructivism often focuses on deconstructing light, space, and material to produce an emotional response. The Jewish Museum in Berlin, designed by Daniel Libeskind, displays the disjointed elements of deconstructive architecture. The frantic zig-zag design and irregular voids symbolize the tumultuous journey of the Jewish people and the void left behind by those lost in the Holocaust. Secondly, deconstructive architectural buildings use a mix of distorted lines and planes to disrupt traditional forms. The Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, by Frank Gehry, is a prominent architectural feat that embraces dynamic disruption, controlled complexity, and slanted surfaces. Thirdly, deconstructive architecture creates a sense of movement or instability in static structures. The City of Capitals in Moscow, Russia, by the NBBJ architecture firm, consists of multifaceted angular towers representing the cities of Moscow and Saint Petersburg. The City of Capitals challenges the viewer’s perception of stability through disjointed building segments that appear to be in rotation.

9. Brutalist architecture

Brutalist architecture is an architectural style that uses exposed concrete to evoke a strong yet simplistic aesthetic. Brutalist architecture focuses on strong geometric shapes and exteriors that resemble a fortress of minimalist construction. The emergence of brutalist architecture began in the 20th century during the 1950s and 1960s to tone down the ornamentalism of previous years. For example, the Royal National Theatre in London by Denys Lasdun is a paradigm of brutalist architecture. The Royal National Theatre displays exposed concrete, uneven angles, and geometrical patterns. The vast block-like shape of the Royal National Theatre suggests a modular quality that defines the functional zones of the structure, including three separate theaters. Brutalist architecture is historically significant for inspiring the reconstruction of buildings after World War II. The brutalist architectural style carved its niche in the history of evolving architectural styles as a testament to the beauty of raw, unadorned functionality.

There are three primary characteristics of brutalist architecture. Firstly, brutalist architecture showcases the unyielding presence of exposed concrete as a hallmark design. The Boston City Hall in the United States demonstrates the use of raw concrete due to its façade featuring the coarse material. Secondly, brutalist structures exude a fortress-like presence emphasizing security and stability. The Barbican Centre designed by Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon in London is a testament to the sturdy exterior common among brutalist architecture. The Barbican Centre features a structured flow of compartmental units that creates balance. Thirdly, brutalism focuses on bold geometric shapes. Habitat 67 by Moshe Safdie in Montreal encapsulates an intricate arrangement of concrete cubes that play with form and space. Habitat 67 creates a modular stronghold against the backdrop of a lively Montreal.

10. Parametric architecture

Parametric architecture is a modern style of creating structures with dynamic, intricate, and adaptable features. Parametric architects use mathematical formulas and parameters to produce detailed and unconventional forms of geometries. The parametric style of architecture replicates mirroring patterns observed in nature using algorithms and mathematical parameters. Parametric architecture is a relatively new form of architecture, and gained traction in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. For example, The Peak, created by Studio Symbiosis, showcases the dynamic quality of parametric architecture. The architects highlight the Peak’s functionality through parametric methods to improve ventilation, shading, and energy efficiency. The patterns of the Peak are influenced by nature and use hexagonal patterns that are found in beehives. Parametric architecture is significant to architectural history because the design uses sustainability and innovative ways to create a structure. Parametric architecture seeks to bridge the gap between nature, mathematics, and technology to feature the most efficient design elements.

Parametric architecture uses innovative designs and technology to create amazing structures. Parametric architecture structures share three distinct characteristics. Firstly, the parametric architecture uses unconventional forms of geometry in its design. The Heydar Aliyev Center by Zaha Hadid, in Azerbaijan, has an unconventional layout and a smooth and curvy design. Secondly, the parametric architecture uses intrinsic patterns that are inspired by nature. The Beijing National Aquatics Centre in China resembles an image of a cube made out of water molecules. The bubbly façade features a formation strategically designed to catch and reuse water, adding to its functionality and natural essence. Thirdly, parametric architecture is technologically advanced and uses innovative methods to serve its purpose. The Al Bahar Towers in Abu Dhabi uses sun shades that open and close depending on the sunlight conditions. The result is a merging of aesthetic design and functionality.

11. Residential architecture

Residential architecture is a broad term encompassing a range of planned housing projects for individuals, families, or communities. Such projects balance the functional and aesthetic needs of their occupants in order to create comfortable, harmonious living spaces. The ethos of residential architecture has existed as long as humanity has built housing for itself. For example, early Mesopotamians from the Ubaid period (6500-3800 BCE) constructed simple mud-brick homes specifically for housing commoners. However, residential architecture as a formal study is a relatively modern phenomenon, emerging as a facet of academic architectural theory in the 19th century. Institutions like the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris were pivotal in categorizing distinct fields of architecture in response to rapid industrial urbanization.

One of the most iconic examples of residential architecture is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, constructed in 1937. Wright designed it to challenge traditional notions of residential architecture as purely utilitarian, demonstrating how human habitation could harmoniously coexist with its natural environment. However, residential architecture by no means needs to be so aspirational. Everything from simple thatched-roof huts to brick row houses serves the core purpose of providing a comfortable shelter that is highly functional within a locale’s environmental and economic contexts.

12. Commercial architecture

Commercial architecture is the development of structures for commercial or business purposes. Commercial architecture concentrates on developing spaces that are practical and efficient for large-audience use. The rise of commercial architecture in the modern era began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For example, the Trump Tower by Der Scutt, located in New York City, is a famous example of commercial architecture. The Trump Tower represents luxury and wealth and features a remarkable expansive retail section, eatery, and resident building. Trump Tower became a place where people could go to do upscale shopping as well as serving as a residence building for people of wealth. The historical importance of commercial architecture stems from its cultural and economic significance in the world and weaves together the evolving global world.

There are three general characteristics of commercial architecture. Firstly, commercial architecture focuses on developing spaces for commerce and trade purposes. The construction of the Empire State Building in New York City is an economic opportunity for the city and an architectural marvel. Secondly, commercial architecture serves a dual purpose of business and leisure. The Marina Bay Sands Mall in Singapore offers a resort complex with a casino, mall, hotel, and convention center. The multi-use resort is a one-stop experience for all your vacation needs. Thirdly, commercial architecture focuses on creating infrastructure that is practical and efficient. The Fulton Center in New York City uses its space efficiently by providing a major transportation hub connecting retail stores and subway lines. The Fulton Center masterfully amalgamates a major nexus of commerce and functionality.

13. Industrial architecture

Industrial architecture is a design style that offers productive and useful spaces for industrial operations. Industrial architecture rose to prominence as a response to the burgeoning demand for manufacturing and production spaces. Industrial architecture aims to create spaces that have open layouts to maximize utilization and to create space for equipment and operations. The Industrial Revolution created industrial architecture in the late 18th and early 19th centuries because of the rise in demand for manufacturing. For example, the Fagus Factory in Germany showcases industrial architecture through a clear façade and expansive glass outer look, marking a notable break from the previous period’s use of brick structures. Industrial architecture has historical importance because of its sociological and new technological advancements that the previous periods never had.

Three characteristics define industrial architecture. Firstly, the primary objective of industrial architecture is to focus on building spaces for industrial processes. For example, the Volkswagen Factory in Wolfsburg, Germany, is an archetype of a sustainable manufacturing facility intentionally built to capitalize on the functional space. Secondly, industrial architecture prioritizes natural light with unfinished and exposed elements. For example, the Van Nelle Factory in Rotterdam, Netherlands, showcases extensive large windows designed to optimize workflow and natural light, ensuring an efficient and worker-friendly environment. Thirdly, industrial architecture incorporates large open floorplans. For example, the AEG Turbine Factory in Berlin, designed by Peter Behrens, is a testament to the expansive open layouts common in industrial settings. The spacious interior and robust construction provide the necessary space to house large turbine assemblies while showcasing the aesthetic potential of industrial architecture.

14. Institutional architecture

Institutional architecture is an architectural style that aims to create structures for organizations with a clear and particular purpose. Institutional architecture is adaptable and creates functional and effective spaces for industries such as government offices, courthouses, schools, and hospitals. The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed the construction of various institutional buildings and projects. For example, the United States Capitol Building by William Thornton in Washington D.C. is an institutional architecture building that symbolizes governance. The Capitol Building symbolizes Democratic values and serves as a functional space for government workers. It exudes political reverence through its incorporation of neo-classical design elements. Institutional architecture is historically important because it reflects the values of religious, cultural, and political institutions worldwide.

There are three distinctive characteristics of institutional architecture. Firstly, institutional architecture is adept at conceiving and building libraries. The Library of Trinity College in Dublin stands out as an architectural marvel. Secondly, institutional architecture showcases its prowess through university edifices and encompassing environments. The expansive campus of Harvard University in the United States, along with its array of academic libraries, encapsulates the essence of institutional architectural genius. Thirdly, institutional architecture works to build museums and celebrate human history and artistry. The Louvre Museum in Paris is a repository of a vast array of art and artifacts. It welcomes global visitors to immerse themselves in history and architectural splendor.

15. Landscape architecture

Landscape architecture is a discipline that focuses on creating and managing property based on outdoor spaces. Landscape architecture involves various environments such as landscapes, gardens, public plazas, and parks and incorporates plants, water, and natural landforms. Landscape architecture took off in the 19th century and continued to evolve as a profession into the 20th century. For example, Central Park by Frederick Law Olmsted, in New York City, is a paradigm of landscape architecture. Central Park was designed in the mid-19th century and has an extensive landscape of water, meadows, and woodlands. Central Park features crafted trails and uses landscape architecture to uplift the area. Landscape architecture is of great historical importance because of its role in creating and preserving environmental green spaces in urban developments. Preserving greenspace through landscape architecture creates an oasis between soaring skyscrapers and urban sprawl.

Landscape architecture has three main characteristics. Firstly, landscape architecture involves the creation of new green spaces. The Butchart Gardens by Jennie Butchart, located in British Columbia, Canada, has transformed from a limestone quarry to a gorgeous landscape with themed gardens such as its Japanese Garden and Sunken Garden. Secondly, landscape architecture features sustainable elements within its design. The sustainable design of the Gardens by the Bay in Singapore shows landscape architecture’s innovation in balancing aesthetics and ecological preservation. Thirdly, landscape architecture works to blend a variety of different environments. The Cheonggyecheon Stream Restoration Project in Seoul combines natural waterways and pedestrian pathways. The sprawling pedestrian features allow for functionality that invites people to partake in the public spaces.

16. Interior architecture

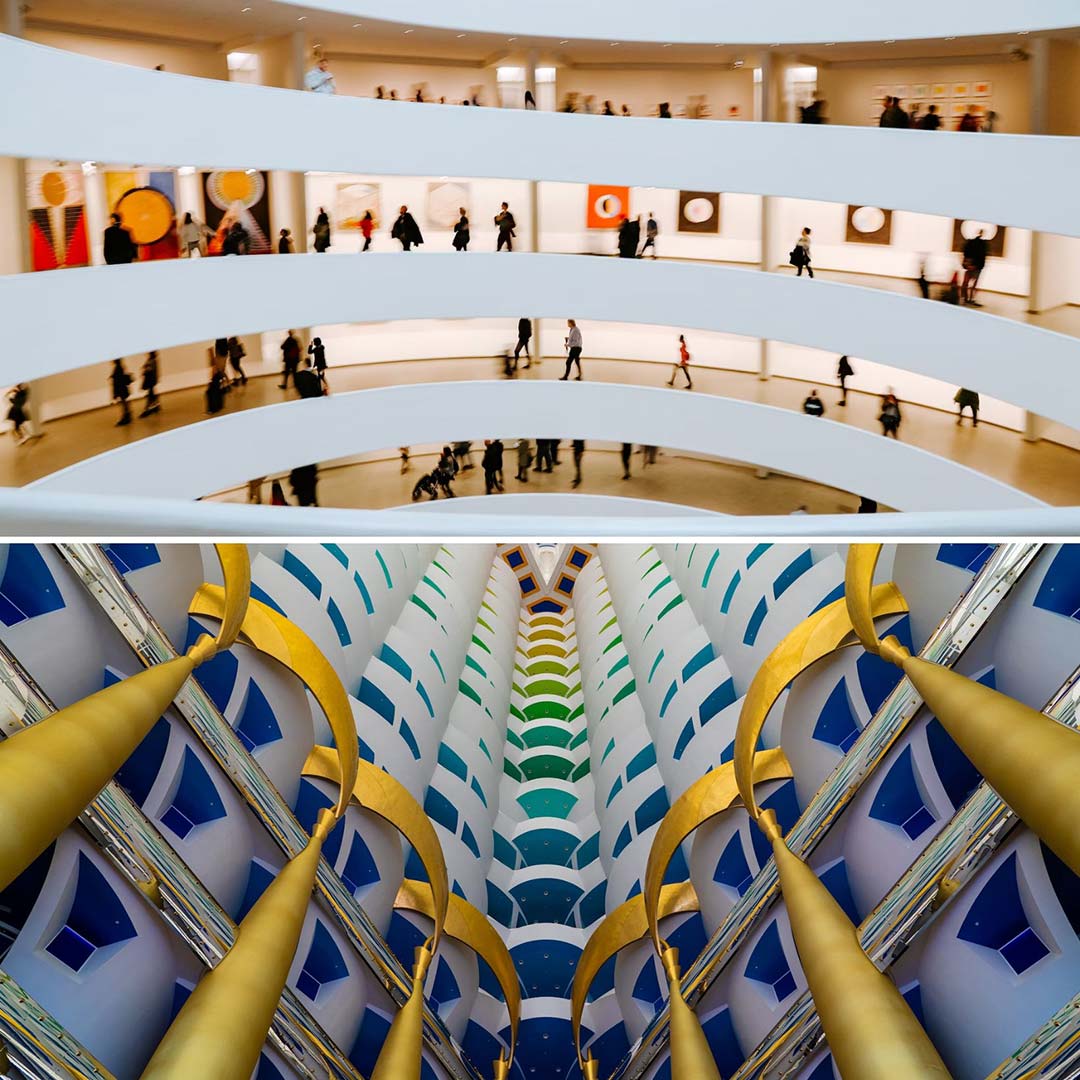

Interior architecture is an architectural discipline that focuses on the layout and design of interior spaces. Interior architecture meticulously orchestrates the design of a building’s interior elements and the integration of materials to create aesthetically pleasing rooms. Interior architecture became popular during the late 19th and early 20th centuries to create harmony between construction and aesthetic space. For example, the distinctive interior style of the Guggenheim Museum by Frank Lloyd Wright, in New York City demonstrates innovation of interior architecture. The museum has a renowned conventional layout and unique features, such as its spiral ramp design and intelligent integration of art styles. Interior architecture is historically important due to its ability to capture the cultural landscape and preserve past architectural elements.

Interior architecture has three definitive characteristics. Firstly, interior architecture uses luxurious and extravagant detailing. The luxury hotel Burj Al Arab by Khuan Chew, located in Dubai, has an interior designated to luxury and opulence. The interior architecture of Burj Al Arab offers an intoxicating visual experience due to the multistorey structure’s vertical onslaught of rooms. Secondly, interior architectural design highlights versatility and depth to get the most out of a structure’s floor plan. The Glass House in Connecticut by Philip Johnson encapsulates the epitome of an open floor plan. The free flow of living space allows for flexibility and functionality to prosper. Thirdly, interior architecture melds the essence of the past alongside contemporary designs. The Hearst Castle in California features Roman influence throughout the interior pools, statuaries, and mosaics. The living quarters within Hearst Castle are an amalgamation of Gothic, Neo-Classical, and Spanish Colonial, adorning design elements young and old.

17. Sustainable architecture

Sustainable architecture prioritizes the creation of structures that harmonize with their environment and consume resources judiciously. This innovative design philosophy draws on cutting-edge technologies and smart design principles to ensure that buildings have a minimal harmful impact on both the natural world and local communities. The overarching aim is to foster long-lasting, responsible designs that contemplate every aspect of the product’s life cycle, from site choice and material selection to energy consumption and eventual decommissioning. Sustainable architecture makes intentional use of recycled, reclaimed, or rapidly renewable building materials in order to reduce a construction’s environmental footprint. Bamboo, which grows and matures in as few as three years, is a popular alternative to hardwood, as are other natural materials such as straw bales, hempcrete, and even sheep’s wool. Sustainable architects heavily source recycled industrial resources such as concrete, steel, plastic, and glass in order to reduce waste as well as energy costs of producing virgin material.

One of the most famous examples of sustainable architecture is Seattle’s Bullitt Center, which boasts net-zero energy consumption through a large rooftop solar array, total avoidance of toxic building materials, rainwater harvesting, ground-source heating, compost toilets, and natural daylighting. The necessity of such radical concepts is evident in the effort to combat anthropogenic climate change, and sustainable projects are often as much about proof of concept as they are about practicality.

18. Power architecture

Power architecture is a symbolic means for conveying wealth, power, permanence, and authority through construction. It is not a distinct school of architecture so much as it is an ethos of power projection. Examples of power architecture date back to antiquity, with salient examples including the Great Pyramids of Giza, the triumphal arches of Rome, and even the Gothic cathedrals of medieval Europe. However, the concept is very much germane to modern architectural goals, with monumental works like the Burj Khalifa symbolizing the economic might and technical prowess of the United Arab Emirates through its unprecedented height. Similarly, the aluminum cap of the Washington Monument was a display of the US’s ability to produce this then-expensive alloy.

There is no single style that encapsulates power architecture, but there are three unifying characteristics shared by most examples. First, power architecture relies on sheer scale to perpetuate the perception of unrivaled power of an authority (be it a state, corporation, or individual). Second, no expense is spared to convey wealth and endurance through ultra-premium materials like marble and gold. Finally, power architecture is inherently symbolic, making ample use of culturally significant motifs, shapes, and iconography.

19. Group housing architecture

Group housing architecture refers to planned residential buildings or complexes meant to accommodate multiple families with some degree of shared facilities. Group housing projects are necessarily diverse in order to serve the varying needs of different populations, but there are three general characteristics shared by most examples. First, group housing tends to feature common spaces like dining areas, recreational facilities, and gardens. These shared amenities foster a sense of community among residents while reducing the costs otherwise associated with individualized amenities. Second, planned community housing strives for the most efficient use of space in order to maximize the number of residents who can live there comfortably. The third major characteristic dovetails with the second in the careful balance between public and private space.

One of the most iconic examples of group housing is Montreal’s Habitat 67, which serves as a proof of concept for modular community planning. Its idiosyncratic staggered container design enabled neighbors to easily interact across each unit’s outdoor terrace while enjoying ample natural lighting, ventilation, and scenic views. Habitat 67 pioneered architecturally radical communal spaces in 1967, but the concept of group housing architecture dates back to the Industrial Revolution as a means to accommodate urban population booms. The Saltaire workers’ village of Yorkshire, England was a product of communal planning that sought to address the squalor of industrial slums. Sir Titus Salt designed his entire model village around a textile mill in a way that supported the productivity of the mill as well as the dignity and livelihoods of its workers.

20. Religious architecture

Religious architecture broadly defines constructions that reflect and serve the spiritual beliefs of those who construct them. Examples of religious architecture are ubiquitous throughout world history, encompassing churches, mosques, synagogues, temples, and shrines back to antiquity. These sites vary widely in their stylistic features but nevertheless share common goals of facilitating religious rituals, inspiring devotion through layout and ornamentation, and asserting the cultural prominence of the religion. One of the most famous examples of religious architecture is the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. It was built by the 6th-century Byzantine Emperor Justinian I as an Eastern Orthodox cathedral but later converted to a mosque following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople. The Hagia Sophia bears a striking mix of Christian and Islamic art, iconography, and architectural features, which together reflect the layered cultural mosaic of Turkish history.

Religious architecture is a cornerstone of human civilization, serving not only as places of worship but as centers of cultural, intellectual, and philanthropic activity. Moreover, religious constructions provide some of the earliest evidence of communal cooperation. For example, one of the oldest extant buildings in the world is Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, which archaeologists date back as early as 9500 BCE. The exact nature of the site is a matter of debate, but evidence suggests that Göbekli Tepe served as a gathering place for ritualistic activity.

21. Governmental architecture

Governmental architecture refers to structures that symbolize or facilitate the governance of a given jurisdiction. These buildings typically symbolize the authority, stability, and values of the state or institution they serve. Common examples of governmental structures include courthouses, town halls, embassies, palaces, as well as executive and legislative buildings. These buildings usually occupy prominent locations central to the town or city they serve in order to facilitate easy access by the public. However, governmental architects tend to balance access with security in order to ensure continuity of service even amidst societal instability.

The Kremlin of Moscow is emblematic of the dynamics that shape governmental architecture. Its initial construction as a wooden fortress in the 12th century has been revised and improved upon by successive Russian leaders. The most notable of these renovations occurred during the reign of Ivan the Great in the 15th century. He not only fortified the structure with red brick but enlisted prominent Italian architects to reshape the Kremlin, blending the latest Renaissance fashions with traditional Russian stylings in an effort to elevate both. It was under Ivan that the Cathedral of the Assumption was constructed in a move to consolidate religious, cultural, and political power. Later additions further bolstered the prestige of the Kremlin (and thus, the state), such as the Grand Kremlin Palace completed by Tsar Nicholas I in 1849. Today, the Kremlin serves as the seat of power for the Russian government as well as a locus for Russian history and culture.

What are the aesthetic elements in architecture?

Aesthetic elements in architecture are concepts that influence the design of a structure. Architects consider these concepts to dictate the function, visual impact, and experiences humans have within, around, or while viewing a building. The list below summarizes the main aesthetic elements in architecture.

- Form and shape: Form and shape define a building’s composition. Form refers to the three-dimensional organization, function, and appearance of a structure while shape is the two-dimensional, geometric elements that affect our perception of a structure.

- Line: Lines in architecture are edges and boundaries created by interconnecting visual paths. They define shape and form as well as influence the aesthetic impression through visual direction created by different types of lines.

- Color: Color in architecture is an aesthetic element that impacts the visual mood, depth, movement, and texture of a structure. Warm, cool, and neutral colors influence a building’s design, stimulating different experiences depending on the palette.

- Texture: The aesthetic element of texture defines the visual and physical surface qualities of a structure. These qualities impact the sensory experience of a structure, leading architects to be selective about the texture of materials used.

- Light: Light as an aesthetic element is used to define a building’s form and features. Light additionally influences spatial perception, mood, and functionality, achieving different results depending on the type of light used.

- Scale: Scale in architecture compares or relates a structure’s size to another object. Architects use scale to consider the human experience within or around a structure as well as the prominence or intimacy of a design.

- Space: Space in architecture is a three-dimensional physical area within and around a structure. Architectural borders define space while the spatial layout of a structure influences how it is organized, functions, and is aesthetically experienced.

- Movement: The aesthetic element of movement refers to the flow of a structure’s design. Movement affects how humans move through a space, as well as how other elements influence our perception of flow in a given area.

- Symbolism: Symbolism refers to the meaning a structure conveys. Symbolism is cultural, religious, or historical and imparts an artistic message the architect desires to share with viewers or inhabitants of a structure.

- Context: Context in architecture encompasses the physical, environmental, social, historical, and aesthetic factors that influence a building’s design and development. Architects consider the context of a structure to better determine its intent and visual impact.

1. Form and shape in architecture

Form and shape in architecture refer to the aesthetic elements that define the composition of a building. Form encompasses the overall three-dimensional configuration of a building, including its size and the physical exterior and interior features that define its design. The three-dimensional spatial organization, functionality, and aesthetic impression a building evokes are all examples of form. Meanwhile, shape in architecture is two-dimensional, encompassing geometric elements created by boundaries and edges that distinguish form. A building’s shapes affect its aesthetic by influencing our perception of the visual environment and how the form of architectural elements appear balanced or unbalanced. For example, the Colosseum in Rome, Italy presents a two-dimensional elliptical or oval shape from the sky that evokes a cohesive, symmetrical design.

All types of architecture reflect form and shape as they are fundamental elements of design. Architects use these elements to determine the composition of a structure and the distinct impression it leaves. This choice is dependent on any number of factors, such as cultural influences or artistic vision. Consequently, architects have different approaches and philosophies regarding shape and form. For example, the quote by American architect Louis Sullivan, “Form follows function,” states that the building’s form (and by extension shape) should prioritize its intended purpose. Sullivan himself designed structures like the Wainwright Building which emphasizes square shapes and simple forms that are practical and conventional. However, architectural types like deconstructivist architecture challenge this idea. Deconstructivism distorts form and shapes through jutting angels and irregular figures, prioritizing aesthetics over functionality by causing humans to question the three- and two-dimensional composition of a structure.

2. Line in architecture

Lines in architecture are another core element referring to paths that connect two or more points to create edges, boundaries, and patterns. Lines are fundamental to architectural design as they evoke shape and form by defining the visual paths and limits of a building’s composition. For instance, four different types of lines affect the visual impression of architectural designs. Firstly, horizontal lines are explicit or implied paths running parallel to the horizon. These lines prompt stability, balance, and space by extending the perception of length and guiding the human eye along a level path. Secondly, vertical lines in architecture run perpendicular to the horizontal. These lines promote the height, elevation, and grandeur of a structure. Thirdly, diagonal lines are implicit or explicit paths that draw the eye at a slanted angle. Diagonal lines create a sense of movement by directing our gaze away from the horizon at an angle, generating interest and skewing away from the symmetry of vertical and horizontal lines. Finally, curved lines are arched, irregular visual paths. Such lines are more organic, emphasizing asymmetry and flow. Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí was partial to curved lines, famously stating that “The straight line belongs to men, the curved one to God.” Gaudí’s words mean that straight horizontal, diagonal, and vertical lines are key to architecture, but curved lines are visually stimulating and more in line with nature.

The usage of lines is visible in all types of architecture, but some styles emphasize lines more acutely than others. For example, classical architecture stresses straight vertical and horizontal lines through features like columns to impose a sense of orderliness and grandeur. Meanwhile, deconstructivist structure challenges conventional applications of line through fragmentation and distortion whereas modern architecture leans on clean, stark lines that are largely inorganic. Parametric architecture additionally reflects the architectural element of the line by imposing complex curves and diagonals that draw the eye. Conversely, the linework of postmodern structures is less complex but similarly experimental—building off the starkness of modern buildings to be more intricate and whimsical.

3. Color in architecture

Color in architecture is a foundational aesthetic element that determines the visual impression of a structure’s exterior or interior. Color affects a design’s mood as well as the appearance of depth, movement, and texture. For example, different types of colors prompt different types of impressions, similar to shapes or lines. The key distinction is that color pertains to the hues and visual attributes. Warm colors like reds, oranges, and yellows create comforting or energizing moods, provide an enclosed yet comfortable sense of depth and movement, and visually stimulating textures. Cool colors like blues and greens foster serene moods, deepening the illusion of depth and airiness of space so it appears larger and textures appear smoother. Meanwhile, neutral colors such as whites, grays, and beiges stimulate a relaxing and centered aura, reducing the movement or stimulation of elements and prompting either an open or enclosed space depending on the colors used.

The choice and use of color vary among architects and the types of structures they design. For instance, Antoni Gaudí remarked that “Color in certain places has the great value of making the outlines and structural planes seem more energetic.” The quote emphasizes the flexibility of color in architectural design as Gaudí utilized a broad and vivacious palette in his work. One type of architecture that emphasizes color is postmodern designs and religious structures. Postmodern architecture capitalizes on color, utilizing it to create contrast and visual distinction to draw the human eye. Meanwhile, religious architecture such as Gaudí’s own Sagrada Familia leverages colors as symbolism with specific palettes representing fundamental elements of a region, culture, or belief. The Sagrada Familia Cathedral in Barcelona, Spain emphasizes color through stained glass, mosaics, and decals to illustrate religious themes while creating a whimsical mood that makes it distinct from other types of Gothic and Art Nouveau architecture.

4. Texture in Architecture