Art is a creative process intended to produce an end result that evokes an emotional reaction in its intended audience. A work of art functions as a vessel through which the artist expresses an idea, feeling, value, or experience. Artists select their medium and techniques with discretion and intentionality in order to heighten the emotional impact of their message.

The precise definition of art has been a subject of philosophical debate throughout history. However, it is generally accurate to say that art requires both a creator and an intended audience. The nature and value of this communicative interplay between artist and audience is dictated according to any number of eight core motivations of art: communication, entertainment, expression, social inquiry, social causes, commercialism, psychological health, and propaganda. Each motivation makes use of unique aesthetics and cultural cues to facilitate its purpose to emotionally impact or influence its audience in some meaningful way. Interpretation of a work of art is always subjective to some extent due to its inherent humanism, but both artist and audience typically embrace subjectivity as a means to enrich human experience and perspective.

Most common forms of art largely fall into visual, applied, performing, literary, conceptual, folk, craft, or martial disciplines. Every discipline has its own mediums, materials, techniques, traditions, aesthetics, cultures, and intentions which make its artworks transcend their mundane components into a meaningful experience.

There are, however, misconceptions about what art is and isn’t. For example, art does not necessarily have to be aesthetically pleasing; in fact, some of the most effective art specifically challenges traditional norms dictating aesthetics, meaning, or even venue. Moreover, works that lack creative intention beyond mundane or utilitarian purposes are not typically considered artful. Accidental or natural formations usually do not qualify as art, as they once again lack intentional creation.

Below, we delve into the purpose, motivations, forms, and legalities of art in an attempt to clarify the definition of this ubiquitous but often misunderstood mode of human expression.

What is the purpose of art?

The purpose of art is largely subjective and varies depending on cultural, historical, and individual perspectives. Art is most often functional in its ability to evoke an emotional or intellectual reaction in its audience. The range of possible reactions is typically anticipated by the creator of the artwork, who manipulates the techniques, medium, and context of the art to maximize its impact. Generally, this drive to foster reactions is based on the personal convictions and values of the artist, who strives to express an idea, sentiment, or aesthetic value in order to advance a cultural milieu. Moreover, artwork is often a means of nurturing the subject of an artist’s passions, providing a means for self-actualization through vision, craft, and passion for human connection. To illustrate this point, American author and essayist Chuck Klosterman penned the following quote.

“Art and love are the same thing: It’s the process of seeing yourself in things that are not you.”

What are the motivations behind art?

The motivations behind art are diverse and multifaceted, and often driven by the artist’s desire to express emotions, convey ideas, or respond to social, political, and cultural contexts. Art serves as a medium for storytelling, preserving history, and exploring the depths of human experience. The impetus of creation for a given piece of art is usually only fully understood by its creator but generally falls under one or more of the following categories of motivations.

- Communication in art: The primary motivation for creating art is to communicate ideas, with artists choosing specific mediums to enhance the messages they wish to convey. This practice of using art as a means of communication spans from prehistoric times to the present, encompassing various forms such as visual art and music. Complex themes like social commentary, political messaging, and abstract thought are expressed through art, challenging norms and evoking reflection on societal issues.

- Entertainment as art: Entertainment is a key motivation for creating art, offering an enjoyable diversion from daily life and fostering emotional and intellectual engagement among audiences. Art in entertainment forms, ranging from music to epic narratives, not only provides enjoyment but also serves as a medium for artists to express broader themes like social commentary and personal growth. This intertwining of art and entertainment extends from ancient times to modern-day, demonstrating the enduring human desire for engaging and meaningful entertainment experiences.

- Need for expression: Art is a primal expression of human emotion and thought, serving as a medium to communicate complex ideas and feelings to a diverse audience. While the artist’s control over interpretation is limited, the inherent subjectivity of perception is leveraged to give art multifaceted meaning, reflecting art’s deep-rooted connection to human communication and evolution.

- Social inquiry: Art functions as a critical medium for social inquiry, with artists historically using their work to reflect on society, challenge norms, and advocate for change. This form of art is often subversive in nature and varies in execution across mediums and audiences. It has been a significant tool for social analysis and critique throughout history.

- Social causes: Social causes often inspire the creation of art, offering artists thematic and symbolic material and a receptive audience among those invested in the cause. This form of art (ranging from historical paintings to modern public art and satirical poetry) powerfully encapsulates and promotes revolutionary ideals, political commentary, and protest. Art serves both as a reflection of and a catalyst for societal change.

- Commercialism: Commercialism significantly intersects with artistic motivations, as artists often aim to make their work commercially viable, while commercial entities use art for branding, sales, and marketing. This convergence leads to the creation of commercial art, which is ubiquitous in various forms like logos, advertisements, and product designs, intended to evoke emotional responses and spur actions related to brand association or purchasing decisions.

- Psychological health: Art therapy (encompassing both visual and musical forms) is a valuable tool for fostering psychological health that helps patients manage and express emotions and conflicts through art creation and reflection. This therapeutic approach, effective in treating conditions like PTSD, depression, and autism, facilitates the expression of the unconscious mind and improves cognitive abilities such as memory and concentration.

- Propaganda: Propaganda has been a major driving force behind art throughout history, employed by governments, organizations, and individuals to promote specific political, social, or cultural agendas. Artistic propaganda aims to influence public opinion, evoke emotional responses, and persuade viewers toward certain viewpoints or actions.

Below we discuss the eight primary motivations for art in greater detail, exploring specific examples across mediums, cultures, and time periods.

1. Communication in art

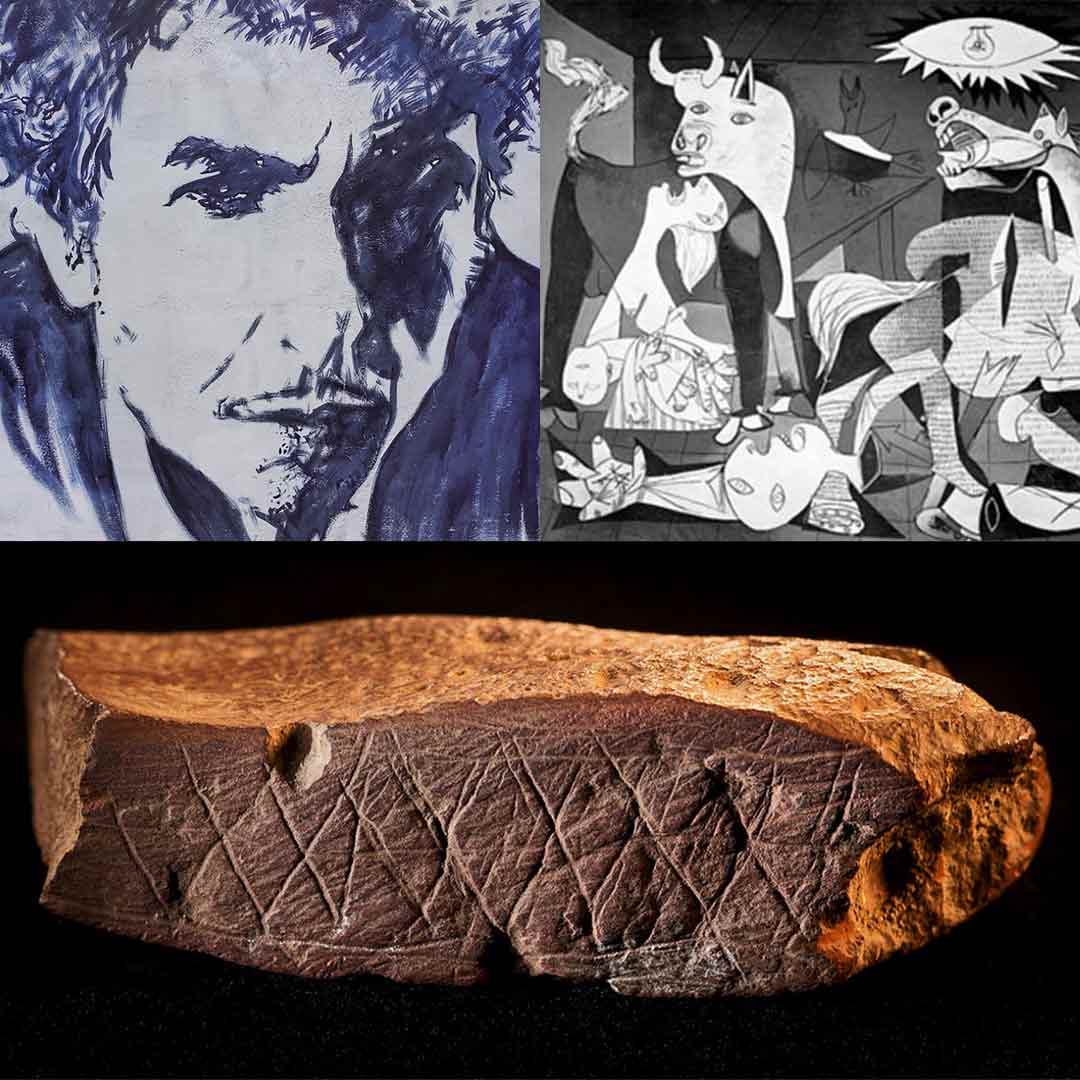

The most fundamental motivation for creating art is to communicate ideas. Artists utilize their chosen medium specifically to elevate the message they are trying to convey. For example, Bob Dylan championed songwriting as a form of social commentary and protest. Dylan’s complex lyricism and free-flowing song structures echo the countercultural ethos of the beat poets. His early songs were heralded as civil rights anthems, such as “Blowin’ in the Wind” which Dylan performed at the 1963 March on Washington alongside Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Bob Dylan deconstructed American values, advocated for truth and justice, and challenged conventional norms of both pop music and broad culture alike through his artistic prowess.

Additional examples of communication in art abound across various mediums. Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” is one of the most prominent examples of transcendent political messaging through visual art. Picasso painted the piece in reaction to the horrors of the Spanish Civil War, specifically the fascist bombing of the Basque village of Guernica. The work makes striking use of heavily distorted cubist figures to convey the chaos and terror of war, with the Spanish bull overseeing a mother grieving over her fallen son. Moreover, Guernica features stark monochromatism and massive scale at over 11 feet tall and 25 feet wide, conveying the bleakness and sheer scale of destruction that war brings.

The practice of communicating through art dates back to prehistoric times, although their messages are often a matter of interpretation to archaeologists today. For example, the Blombos Cave Engravings in South Africa were created some 70,000 years ago, constituting some of the earliest human art yet discovered. They feature repeated geometric patterns commonly believed to demonstrate an early capacity for abstract thought and communication.

2. Entertainment as art

Entertainment is a nearly ubiquitous motivation of art due to the massive demand for enjoyable diversion from the stresses of everyday life. Entertainers who view their work as art seek not only to achieve commercial success and fame but also to provoke emotional and intellectual responses from their audiences. Entertainment media is an accessible vehicle through which audiences may engage with an artist’s concepts and form community bonds around them.

Taylor Swift is one of the most famous examples of an artist and entertainer. Swift’s songs typically focus on emotional vulnerability and personal growth, and these themes are highly resonant among her target audience. However, Swift’s artistry has transcended the songs themselves to encompass broad social commentary. In 2021, she began re-recording her entire back catalog as a form of protest against the predatory practices common to the music industry. This arduous process not only provides new content for her adoring fans to consume but also makes a powerful statement of self-empowerment through refusal to be taken advantage of.

Prominent historical examples of entertainment as art are in the magnum opuses of the ancient Greek poet Homer: “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey”. These epic narratives memorialize the valor and aspirations of ancient Greece through tales of heroism, tragedy, loyalty, and perseverance. Epic poetry was typically performed orally as a form of live entertainment. However, these narrative masterpieces transcended their diversionary intention to render and preserve nuances of ancient Greek mythology, history, and culture centuries beyond the consignment of that civilization to history.

Shell engravings discovered in Java, Indonesia from 540,000 years ago potentially offer the earliest suggestion of the link between art and entertainment. The purpose of these engravings is not precisely known, but their existence makes it clear that homo erectus dedicated time to activities beyond what was strictly necessary to survive. It is still a matter of debate whether these shells represent purely artistic works or whether they are a byproduct of toolmaking processes. However, the Java shell engravings demonstrate that the medium for potential diversionary activities and abstract communication dates back to prehistoric times.

3. Need for expression

The human need for expression is primal, and art is a natural byproduct of that urge. Indeed, human evolution is profoundly influenced by our ability to communicate with one another. Art offers a means to distill one’s own complex thoughts, feelings, and values into a medium that is digestible to a diverse audience. The artist has only finite control over how this expression is interpreted, but the subjectivity of human perception is often taken into account as a means to elevate the work to have multifaceted meaning.

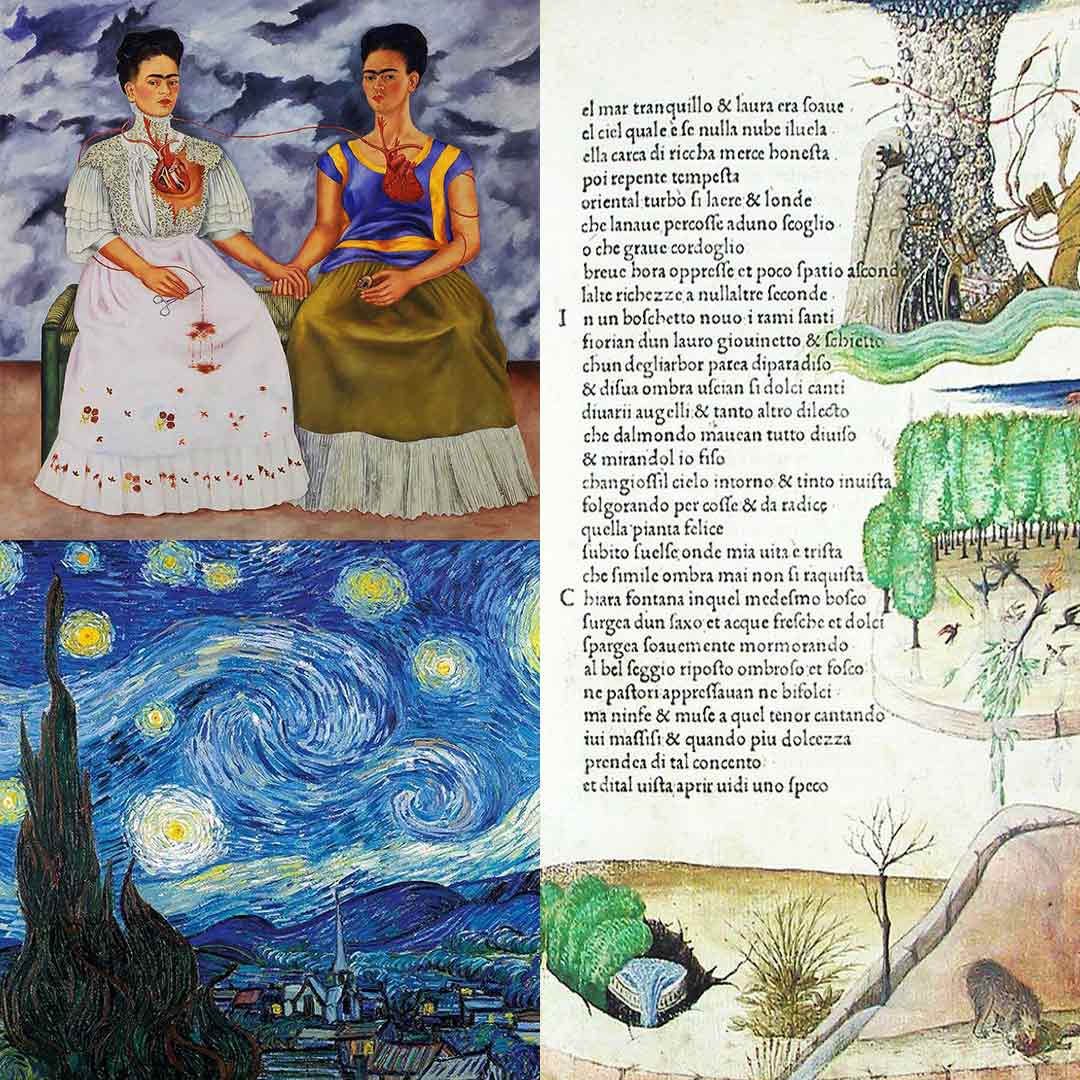

Vincent van Gogh is recognized as a highly expressive artist. Van Gogh’s vivid colors and bold brushwork lent profound dynamism to his paintings, heightening the emotional impact on the viewer. Moreover, he is an exemplar of the impressionistic style in which realism is secondary to emotional depth. Indeed, his most famous painting “Starry Night” reflects the tumult and contrasts in his personal life. Van Gogh composed Starry Night in 1889 at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum, which he admitted himself to voluntarily in an effort to treat his mental health issues. The swirling night sky contrasts with the pastoral calm of the landscape below, offering a glimpse into van Gogh’s coexistent turmoil and tranquility during his treatment.

Frida Kahlo was another painter for whom art represented a profound means of self-expression. Kahlo explored themes of identity, politics, passion, and pain derived from her lived experiences as a childhood polio survivor and as a Mexican woman. Her 1939 painting “Las Dos Fridas” (“The Two Fridas”) expresses a strained inner duality stemming from her mixed heritage and recent divorce from Mexican painter Diego Rivera. The painting depicts two Fridas, one dressed in a Victorian gown and the other in a traditional Tehuana dress. The two are holding hands, but share a symbolically profound physical connection through their exposed hearts, which connect to one another through a shared vein. The European Frida is using scissors to sever a part of the vein, while the Mexican Frida holds a small portrait of her ex-husband. “Las Dos Fridas” is a provocative personal narrative expressing the complex relationship between the aspects of Kahlo’s life that brought her both inspiration and pain.

Art motivated by expression is as old as human culture itself, but it came to the fore during the Renaissance period. The 14th-century Italian scholar and poet Francesco Petrarca (also known as “Petrarch”) advocated for the study of classical texts, which he believed contained the wisdom and learning necessary for a moral and effective life. His collection of sonnets known as “Il Canzoniere” focused on the human experience rather than simply reinforcing religious dogma.

4. Social inquiry

Art is a natural medium through which to conduct social inquiry, and the evolution of the two is deeply intertwined. Artists have used their work to reflect on the society they live in, challenge norms, and advocate for change throughout history. Such art tends to be subversive in intent, although the pointedness of its execution may vary depending on the medium and intended audience.

British art-rock band Radiohead is emblematic of how social inquiry shapes art, and vice versa. Radiohead’s groundbreaking 1997 album OK Computer embedded themes of social alienation, anti-consumerism, political angst, and environmental concern into intricately crafted songs that pushed radio-friendly sensibilities of popular music. The experimental aspects of the album won the band commercial and critical acclaim, but the accompanying demands of fame and industry heightened their sense of myriad disenchantment. Radiohead followed up with the Kid Amnesiac sessions at the turn of the millennium, which broke down the barriers of radio rock and melded the remnants with glitched-out electronica fused with avant-garde lyricism and orchestration. In 2008, the band rejected the premise of the major label altogether and self-released their landmark In Rainbows. In doing so, the band pioneered the digital direct-to-consumer model of reaching audiences, setting the groundwork for later artists like Taylor Swift to further deconstruct the relationship between artist, industry, and audience.

A more subtle example of social inquiry in art is Bill Watterson’s serial comic “Calvin and Hobbes”. Watterson slyly exposed the average American household to subversive themes of nonconformity, loss of childhood innocence, and materialism under the guise of a simple funny-paper. “Calvin and Hobbes” couched profound existential musings in childish hijinks, allowing his form of social inquiry to permeate the collective unconscious, one daily newspaper at a time.

Social analysis through art has existed in one form or another since antiquity, but it notably coalesced during the Renaissance period. A prime example is Hieronymus Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights”, which invites the viewer to consider the ethical implications of human behavior through contrasting depictions of purity, hedonism, and decay.

5. Social causes

Social causes provide ample motivation for the creation of art. Artists who channel a movement not only have rich thematic and symbolic material to draw from, but a built-in audience among stakeholders for the impending change.

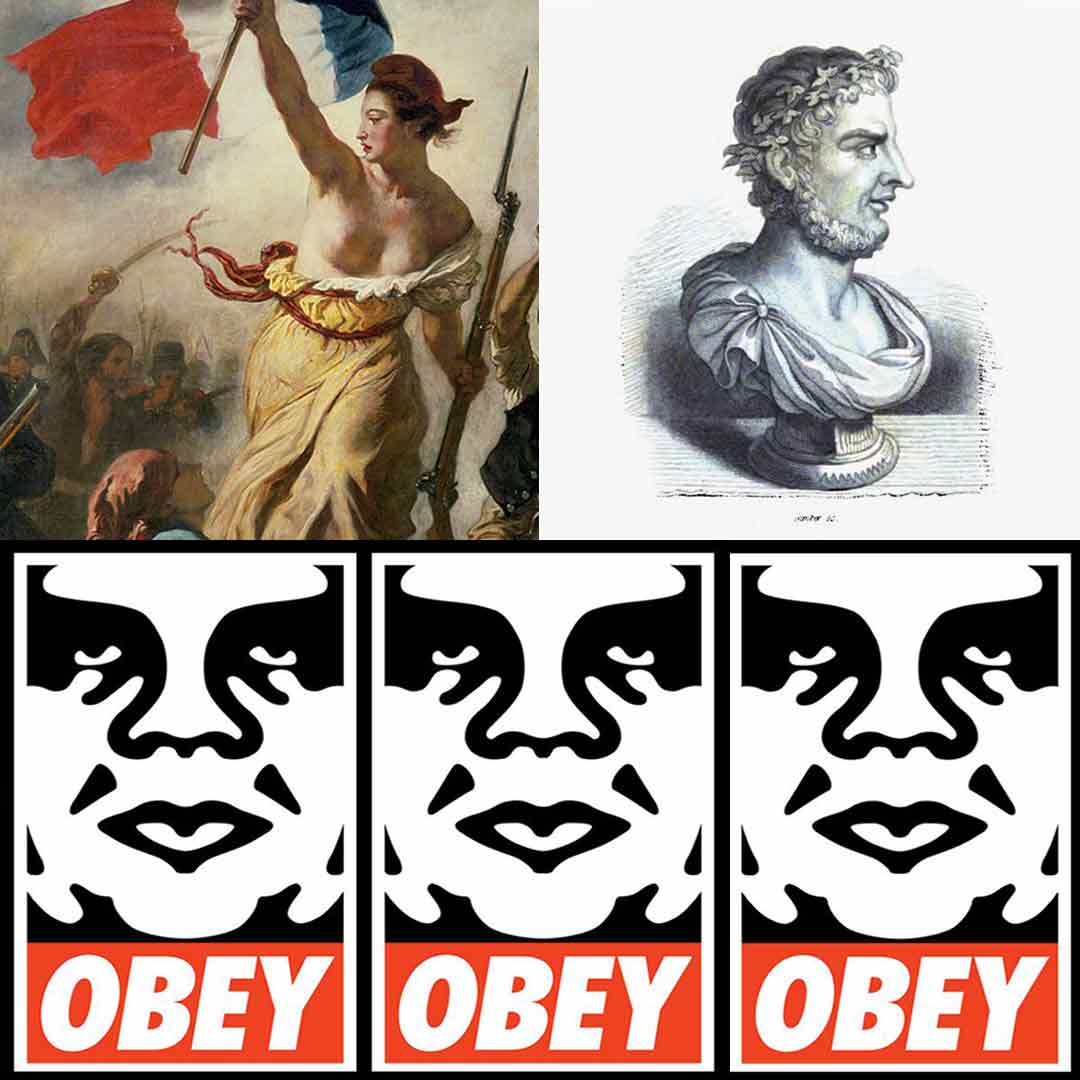

Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 painting “Liberty Leading the People” is a salient example of how art can represent revolutionary ideals. Delacroix composed his magnum opus to commemorate the July Revolution of 1830. It depicts a topless lady Liberty leading a charge of revolutionaries forward to victory in battle. The victors are comprised of representatives from myriad social classes, illustrating the shared goals of the revolution. “Liberty Leading the People” renders the passionate subject matter of the Romantic period through the lens of Realism, symbolizing the coalescence of higher revolutionary ideals into reality.

Charleston, SC native Shepard Fairey is a modern artistic iconoclast, known primarily for his use of public space as a medium for subversive political commentary. He makes extensive memetic use of the phrase OBEY in his public-facing art installations (frequently but not exclusively paired with a propaganda poster-styled stencil of Andrae the Giant) to prompt viewers to question existing power structures. The OBEY meme has its origins in John Carpenter’s 1988 film “They Live”, in which the main character dons special sunglasses that enable him to see society’s ruling elites for what they are: aliens bent on subjugating humanity through capitalist oppression. Fairey’s most famous work, titled “Hope”, made use of similar memetic devices to convey Barack Obama as the face of a politically optimistic movement following the economic and social decline of the Bush administration.

Early examples of art as a form of overt protest date back as far as ancient Rome. The 1st-century poet Decimus Iunius Iuvenalis (also known as Juvenal) wrote pointed satire into his poems, lambasting the decadence and hypocrisy of the aristocracy. His most famous collection of poems, known simply as “Satires”, coined the phrase “panem et circenses” (“bread and circuses”) to describe the means by which Imperial elites kept the populace placated as their rights and freedoms were steadily eroded.

6. Commercialism

Commercialism has a strong intersection with the motivations behind art. Artists are typically exacting in their standards for themselves, which requires an all-in approach that often precludes other meaningful streams of income. Thus, there is a strong incentive for artists to make their work commercially sustainable. Similarly, commercial entities are interested in art for branding, sales, and marketing purposes. The two forces often converge to create compelling commercial art.

Commercial art is in fact ubiquitous, manifesting as company logos, advertisements, and even product design. Virtually every illustration adorning magazines, newspapers, music albums, and movie posters was conceived and/or executed by someone with artistic skill for the purpose of provoking an emotional reaction in the viewer. Although emotionality is a common feature of all art, commercial artists seek to spur action among their audiences. It may be as subtle as mentally associating a brand with a specific sentiment, or as overt as making or inquiring about a purchase.

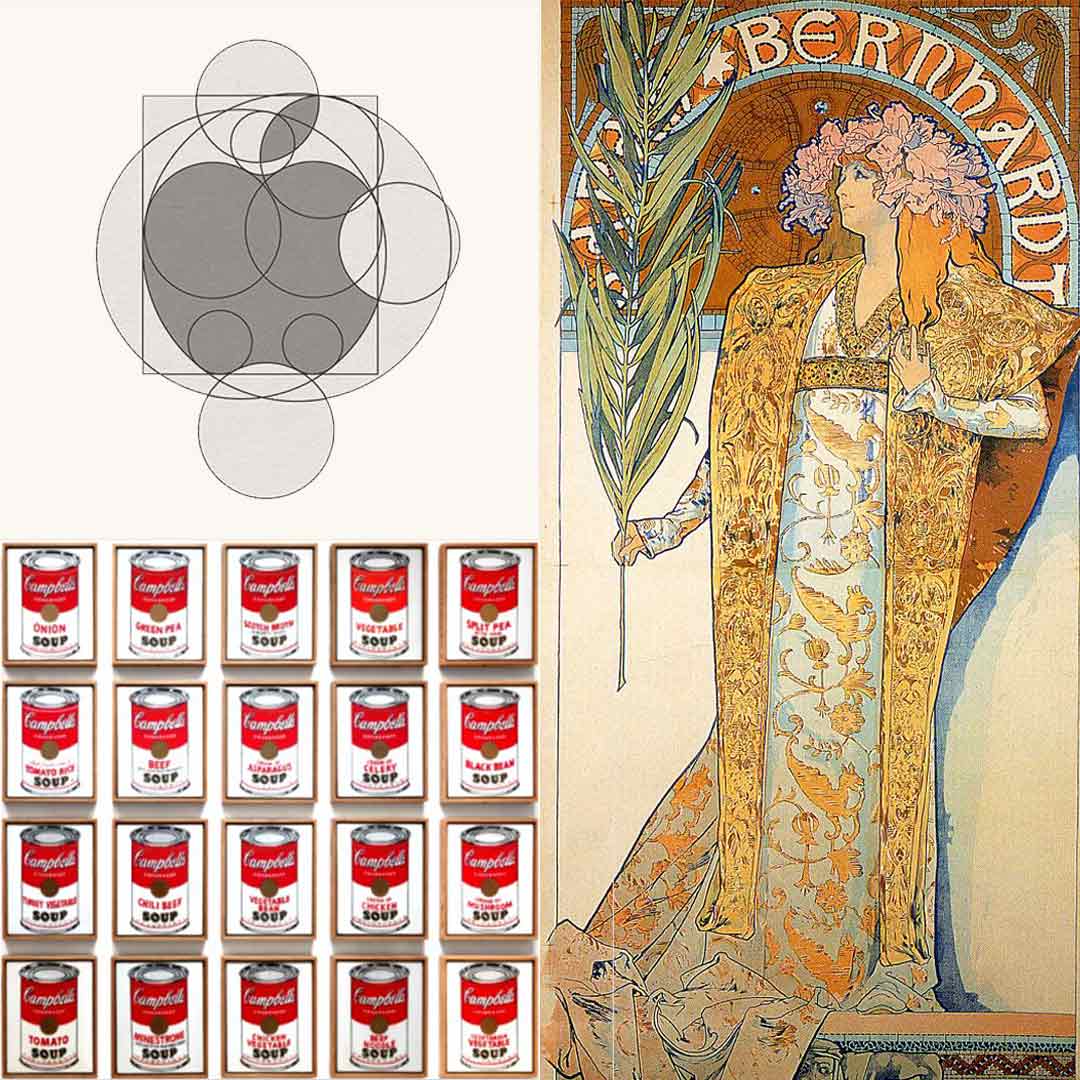

Andy Warhol is an iconic artist who blurred the lines between commercialism and art. His work at New York advertising firms in the 1950s and designing retail window displays laid the groundwork for his interest in the mass production of fine art. By 1962, Warhol had opened up a study in Midtown Manhattan called “The Factory”, where he produced large numbers of silkscreen prints including his famous Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s Soup Cans. Such works elevated consumer culture and the commercialization of everyday life.

Early concrete historical examples of commercial motivations for art include 19th-century Czech artist Alphonse Mucha’s Art Nouveau posters. The most iconic of these advertised for plays starring Sarah Bernhardt. Mucha’s most famous poster is for the French play “Gismonda”, which was first staged in 1894. The poster foregrounds the play’s starlet as the subject, with the overall composition augmented by novel verticality, sinuous linework, and an ornately stylized halo reading “Bernhardt” around the subject’s head. Mucha’s poster immediately proved sensational, elevating both the allure of Bernhardt as well as the role of art in advertising.

7. Psychological health

Art is a useful medium for fostering psychological health. Art therapy helps patients understand, manage, and express their emotions and conflicts through the process of art-making and guided reflection on the resultant work. Even rudimentary expressions of art may be intensely cathartic, as they provide a means to manifest the abstractions of internal conflicts into a concrete, analyzable form. Moreover, art is commonly recommended as a means for improving cognitive abilities such as memory, concentration, and problem-solving skills. Art therapy sees use in the management of serious mental health issues such as PTSD, Alzheimer’s, depression, anxiety, and addiction.

The term “art therapy” was first coined by British artist Adrian Hill in 1942 while recovering from tuberculosis in a sanatorium. Hill found that engaging in drawing and painting during recovery proved therapeutic to his overall mood and convalescence. However, American psychoanalyst Margaret Naumburg is widely regarded as the mother of art therapy. Naumburg believed the contents of the unconscious mind could be expressed through art, allowing for a therapeutic exploration of inner experiences and emotions. She is credited with pioneering the field of art therapy as a cogent and credible field of science.

Music therapy is an adjacent field that blends art with psychological health. Drs. Clive Robbins and Carol Ann Blank established the pivotal Nordoff-Robbins Music Therapy approach throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The Nordoff-Robbins theory posits that every human possesses an innate responsiveness to music, thus providing therapists a medium for interacting with patients who have trouble communicating. The goals of this method (and music therapy in general) include fostering social skills, motor development, and emotional expression. Nordoff-Robbins’ positive outcomes have cemented music therapy as a cornerstone in the treatment of autism and trauma across a diversity of patients worldwide.

8. Propaganda

Propaganda has been a significant motivation for art throughout history, used by governments, organizations, and individuals to promote specific political, social, or cultural agendas. Art as propaganda is designed to influence public opinion, evoke emotional responses, and persuade viewers toward particular viewpoints or actions.

Roman coinage is an early example of how art may serve propaganda purposes. Rome’s first emperor Augustus (who ruled from 27 BCE to 14 AD) minted a series of coins bearing his likeness. The most iconic of these coins was the gold Aureus, which held high value and provided an enduring means for wealthy citizens to store wealth. Roman coins of all denominations were an effective means to disseminate Augustus’ image throughout the vastness of the empire, serving as universal symbols of the Pax Romana. Moreover, Augustus used coinage to portray and normalize his potential heirs in the minds of the public, aiding in the dynastic transfer of power.

Medieval Europe saw widespread use of propagandistic art due to the low literacy rates of the general populace. The Catholic church was especially adept at utilizing the emotional impact of art to both project imminence as well as inspire awe in its doctrine. For example, the ornate carved tympanums adorning church portals often depicted scenes from the Last Judgment, serving as a reminder of Christian beliefs about salvation and damnation. Like Augustus’ coinage, Religious iconography functioned as propaganda largely through hypernormalization, establishing the church’s defacto position of power.

20th-century wartime propaganda was significantly more explicit in its attempt to persuade the public to action. James Montgomery Flagg’s 1917 “I Want YOU for U.S. Army” poster is one of the most iconic and effective examples of artistic propaganda. Flagg depicted Uncle Sam with an intense gaze and pointing finger to break the fourth wall and create a sense of personal responsibility in the viewer to serve their country during wartime. The poster was wildly successful in recruiting personnel for the military and also provided an enduring personification of the US war effort around which the public could rally.

What makes something art?

The intention behind a work’s creation is ultimately what makes something art. Generally speaking, there are two fundamental qualities that something must have to qualify as art. First, art is rooted in human expression and typically manifests the artist’s creativity, emotions, ideas, or worldview. Such expressions may be visual, auditory, literary, performative, or experiential in nature, but they all form a communicative link between creator and audience. Second, art is informed by a creative process that takes its intended audience, medium, and technique into conscious account. An artist manipulates the aspects of their creative process in order to elevate the novelty and message of the artwork.

The fundamental qualities of expression and creative process converge to evoke an emotional or intellectual response in the audience. These responses range from aesthetic pleasure to critical reflection, emotional catharsis, or even discomfort and challenge to one’s perceptions. It is important to understand that art needn’t be conventionally beautiful, nor must it have a wide audience to qualify as art. The ultimate defining characteristic of a work of art is the intentionality of its creator. How a work is created, how it will be engaged by an audience, what it means to convey, and what sort of reactions it is intended to evoke are all major factors that artists are typically highly cognizant of when they embark upon an artistic endeavor.

What is considered Art?

The question “What is considered art?” recognizes that the definition of art is not just a matter of inherent qualities but is also shaped by social, cultural, and historical contexts. This perspective acknowledges that what is recognized as art can vary greatly across different cultures and periods. In some societies, art is closely linked to religious or ceremonial functions, while in others, it’s seen primarily as a form of authentic personal expression or social commentary. The criteria for what is considered art in these contexts thus differs significantly.

Additionally, the role of the art world (a broad term for stakeholders like museums, galleries, art critics, and the broader community of artists and art enthusiasts) is pivotal in determining what is considered art. These entities often influence the way art is perceived, valued, and categorized. A piece that might be overlooked or dismissed in one era might be celebrated as groundbreaking or visionary in another, often due to changes in artistic trends, societal values, or critical perspectives. For example, Vincent van Gogh’s work was largely unappreciated in his time, and the artist lived and died in poverty and relative obscurity. It wasn’t until influential art dealers like Ambroise Vollard created a market for van Gogh’s avant-garde art that his work became widely accepted as having high artistic merit. Similarly, Johann Sebastian Bach’s six suites for solo cello languished as mere academic curiosities until the Spanish virtuoso cellist Pau Casals championed them as works of profound musical craft and beauty.

The concept of art is not static but dynamic, evolving with changes in cultural attitudes, artistic movements, and societal developments. This fluidity is what allows art to continuously adapt and encompass a diverse range of forms, styles, and mediums, reflecting the rich tapestry of human experience and creativity.

What is not considered Art?

Determining what is not considered art can be as complex and subjective as defining what is considered art. This is increasingly true as boundaries of what constitutes art have been continually expanded and challenged throughout history. That said, it is possible to broadly categorize some things as lacking some or all of the fundamental qualities a work of art is typically expected to exhibit.

Purely functional items created solely for utilitarian purposes without any expressive or aesthetic intent are usually not considered art. Such objects tend to be mass-produced with the primary intention of serving commercial interests. However, even these types of objects may transcend their utility when enough intention and craft are put into their making. For example, a plastic student violin bow mass-produced in a factory is not a meaningful expression of art. In contrast, a fine 200-year-old Pernambuco bow made by Fançois Xavier Tourte represents the apex of bowmaking and is capable of provoking an emotional reaction of awe with its masterful blend of form and function.

Similarly, mundane tasks do not usually constitute an artistic performance. Simply leaving your house and walking to the mailbox does little to convey novel aspects of the human experience. However, mundane tasks may be used as devices within performance art; for example, the drama of a play or movie may start with the main character receiving bad news in a letter retrieved from their mailbox.

Works of plagiarism or forgery are commonly rejected as art, despite the aesthetic intentionality or craftsmanship behind their creation. These fakes lack the originality or authenticity of the works they are meant to mimic and usually exist only to further the financial interest of one party at the expense of another.

What did Marcel Duchamp think about the definition of art?

The early 20th-century French-American artist Marcel Duchamp radically transformed the concept of what could be considered art, challenging traditional notions that emphasized aesthetic beauty and technical skill. Duchamp proposed that the definition of art hinges on the artist’s decision and the context, rather than the object’s inherent qualities. His revolutionary approach is exemplified in his famous work “Fountain” (1917), a standard porcelain urinal that he presented as art. This piece, one of his “readymades,” shifted the focus from visual appeal to the artist’s intent in selecting the object. This perspective shift not only questioned the role of the artist and the observer in creating and interpreting art, but also opened the door to conceptual and modern art, where the idea behind the work takes precedence over traditional aesthetic criteria.

What are the Main Characteristics of Art?

The main characteristics of art as a general term apart from any specific medium are as follows.

- Communication: Art largely exists as an alternative form of communication between human beings. Art differs from mundane speech or writing in how it can convey its message through any of the five senses. The range of potential subjects of this message is endless and often seeks to probe the boundaries of human experience. Artistic communication may be explicit or abstract.

- Authenticity: Art functions as an authentic expression of human emotions, thoughts, and concepts. A work is considered inauthentic when it exists solely to fulfill mundane, utilitarian self-interest such as the accumulation of wealth. Artists strive to form genuine emotional connections with their audiences.

- Aesthetics: Aesthetics are sensorial qualities through which an artwork’s audience perceives its emotional content. Aesthetics may be rooted in a specific style or tradition as readily as they may be defined by their rejection of these norms. An artist considers their work’s aesthetics objectively against the range of possible subjective experiences it may elicit in its audience.

- Interpretability: Works of art primarily exist to be interpreted by an audience. The beauty of interfacing with art is that one’s perception of it is holistically subjective. Even an educated audience will have their objective understandings of the modes, themes, and devices a work portrays tempered by the temporal and sensory experience of observing the art. Forming interpretations of art offers a profound means to reflect upon and challenge one’s own perceptions.

- Originality: Artists strive for originality, even when they operate within a preexisting milieu. Works of art may be iconoclastic in nature (rejecting or transcending their contexts or devices) as readily as they may conform to or elevate traditional elements of their being. This spectrum belies a common root in the originality of an artist’s unique ability to conceive a mode of artistic communication, and then choose to iterate or reject it according to the means of their oeuvre.

What are the stages of art creation?

1. Preparation stage of art

The preparation stage of art entails four main parts: conceptualization, acquisition of materials, development of skills, and design.

- The artist must create a solid concept for their work. This entails defining a message, sentiment, or experience the work must convey, as well as who and where the audience for this concept will be.

- The artist selects and acquires the necessary tools and materials for the creation of the piece of art. For example, these may include paint and brushes for a visual artist, sheet music for a musician, or a venue and props for a thespian.

- The artist identifies skills or techniques required to execute their vision, then hones them to the appropriate level. A vocalist will practice scales, arpeggios, and articulation exercises and study the libretto in preparation for their concert; a sculptor will carefully study the rudiments of shape that underpin the form of their design.

- The artist designs the overall process they’ll use to achieve their final result. An author will outline their story and characters, while a ballerina will set a regime to memorize the choreography and identify its more difficult movements.

2. Creation stage of art

The creation stage of art takes action upon their planning in three phases: execution, revision, and finalization.

- The artist embarks upon their endeavor in earnest, and executes the design laid out in the preparation stage. They have all the materials, skills, and planning required to bring their concept to life. Initial iterations are rough sketches of the final product, and incrementally become more well rendered according to the design process.

- The artist reaches an initial stopping point, takes a step back, then reassesses the work they’ve done so far. They may seek the feedback of a peer or mentor, or simply sleep on the fruits of their labor up to this point. The artist will then determine what weak points remain, make a plan to address them in an expedient manner, and then execute once again. This phase may be repeated until the desired outcome is achieved.

- The artist achieves a high degree of confidence that the work is satisfactory for its purpose. Most art is never truly completed, but minor imperfections are tolerated as inconsequential to the audience’s perception of the work. The artist then presents the work to their audience, be it through an art gallery, recital, publication, or stage performance.

3. Appreciation (reflection) stage of art

The appreciation stage of art is where the work ceases to belong solely to its creator and is shared with the audience. The audience engages with the art and then reflects on the experience in four phases: engagement, interpretation, analysis, and discussion.

- The audience directly engages with the work of art. The piece makes its impact through all the intended sensory vehicles as well as the context in which it is shown. Prose or poetry is read, paintings are observed, and live performances are heard, seen, and felt.

- The audience forms interpretations of their experiences. This happens in real-time as well as in retrospect. A gallery viewer may marvel at the masterful use of color and values to augment a painting’s composition; a concertgoer may feel consumed by the harmonic tension and release or resonate with a leitmotif; the audience of a play may erupt in laughter or collectively shed tears at the denouement.

- After the sensory interpretation is complete, intellectual analysis begins. The audience reflects on what they have just experienced, what it means to them, and why it matters. They may recall specific techniques used to heighten a theme or speculate as to the details of the artist’s creation process. Audiences will reconcile whether their interpretations align with the artist’s intentions, and ponder whether any gap reflects more on themselves or the artist. The artwork and artist will be compared to similar artists in a natural attempt to categorize and place them among the greater artistic milieu.

- Following a critical mass of analysis, audience members share their thoughts and feelings with their peers. Peers will discuss their agreements and disagreements alike, narratives will form, and criticism will coalesce in forum. Such criticisms ascribe merit to the work, highlighting strengths and weaknesses relative to what has come before. The artist may choose to engage with this feedback, or they may choose to ignore it. Regardless, discussion in both casual and academic fora is a natural, expected outcome of artistic execution that helps enhance understanding and appreciation for the work and its creator.

What are the different forms of art?

There are nine different forms of art that broadly encompass the vast range of artistic modes of expression.

- Visual arts: communicate through visual elements like color, shape, and composition. Visual art includes painting, sculpture, drawing, and photography. Historically significant periods include the Renaissance (14th-17th century) with artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, the Impressionist movement (late 19th century) featuring artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, and Modernism (late 19th and 20th centuries) with Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí. These arts range from two-dimensional paintings and drawings to three-dimensional sculptures and installations, each era marked by distinct styles and techniques that reflect the evolving nature of visual expression.

- Applied arts: blend aesthetics with functionality, as seen in architecture, graphic design, fashion, ceramics, and jewelry design. Key periods include the Art Nouveau movement (late 19th to early 20th century) with architects like Antoni Gaudí, the Bauhaus school (1919-1933) which revolutionized modern design, and the Art Deco era (1920s-1930s) notable in fashion and architecture. These arts demonstrate the human desire to infuse everyday objects with beauty and design, making the functional also visually and aesthetically appealing.

- Performing arts: are dynamic forms that combine movement, sound, and visual elements to tell stories and evoke emotions. Performance art encompasses theater, dance, film, music, and opera. Notable periods include the Elizabethan era (1558-1603) with playwrights like William Shakespeare, the Romantic period in music (19th century) with composers like Ludwig van Beethoven, and the Golden Age of Hollywood (1930s-1950s) in film. These arts are characterized by live performances and the unique ability to engage audiences in shared, experiential moments.

- Literary arts: rely on language to weave narratives, express ideas, and stir emotions. Literary arts include novels, poetry, essays, and letter-writing. Significant eras include the Renaissance, which saw the works of William Shakespeare, the Romantic period (late 18th to mid-19th century) with poets like William Wordsworth, and the Modernist era (early to mid-20th century) with authors like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. These arts use the written word to transport readers to different worlds, challenge their thinking, and reflect on the human condition.

- Conceptual art: focuses on ideas and concepts over traditional aesthetics. Conceptual art emerged in the 1960s as a challenge to the art establishment. Artists like Marcel Duchamp, with his readymades, and Yoko Ono, known for her avant-garde performance pieces, were instrumental in this movement. Conceptual art invites viewers to engage with the artist’s vision, often provoking thought and discussion beyond the visual aspect of the work.

- Folk art: reflects cultural, religious, or ethnic traditions, often created within a community and passed down through generations. It includes various mediums like textiles, pottery, and woodworking. Folk art is not tied to a specific historical period but evolves with the cultural practices and traditions it represents. It serves both utilitarian and expressive purposes, embodying the cultural identity and heritage of its creators.

- Craft art: involves creating objects by hand, often with a focus on material and technique. Craft art spans disciplines like glassblowing, woodworking, knitting, and embroidery. Notable movements influencing craft art include the Arts and Crafts movement (late 19th to early 20th century), which emphasized handcraftmanship as a reaction against industrialization. Craft art is celebrated for its attention to detail, skill, and the personal touch of the artisan.

- Martial arts: a blend of physical skill, philosophy, and combat techniques, vary across cultures, with forms like Karate (Japan), Taekwondo (Korea), and Kung Fu (China). Historically, these arts have roots in ancient civilizations and have evolved over centuries. Figures like Bruce Lee (1940-1973) have popularized martial arts globally, showcasing their blend of physical prowess and philosophical depth. Martial arts are unique in their combination of artistry and combat, offering both a physical discipline and a means of self-expression.

What are the critiques for the characteristics of art?

The characteristics of art are a perennial subject of critique and debate. Art is a fluid and subjective field, so its defining characteristics are open to challenge. Three prominent critiques are illustrated below.

- Subjectivity of aesthetics: Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume (1711–1776) contended that beauty and aesthetic value are subjective, existing in the mind of the beholder rather than as inherent qualities of an object. In his essay “Of the Standard of Taste” (1757), Hume emphasized that personal taste and cultural differences play a crucial role in how art is perceived and valued. This critique challenges the notion of universal aesthetic standards in art, highlighting the role of individual experience and cultural context in shaping one’s perception of art.

- Artist’s intention versus the audience’s interpretation: French literary theorist and philosopher Roland Barthes (1915–1980) argued against prioritizing the author’s intended meaning in interpreting literary works in his influential essay “Death of the Author” (1967), suggesting that the meaning of art emerges from the audience’s interpretation. This perspective posits that the viewer’s or reader’s experiences and interpretations are as valid as, if not more important than, the creator’s intent. This critique has significantly influenced how art and literature are analyzed, shifting the focus from authorial intent to the viewer’s or reader’s engagement with the work.

- Commercialization and institutional influence in art: French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930–2002) examines how cultural tastes and preferences are influenced by social and economic factors in his work “Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste” (1979). He argued that the art world, including institutions like museums and galleries, and the market dynamics significantly shape what is considered valuable or legitimate art. This critique raises concerns about the impact of commercial and institutional forces on artistic expression and recognition, suggesting that these external factors can sometimes overshadow artistic merit and creativity.

What are the laws against plagiarism of art?

Laws against the plagiarism of art are integral to maintaining the integrity and originality that are central to the creation and critique of art. These laws are rooted in the concept of intellectual property, protecting artists’ rights and ensuring they receive recognition and compensation for their work. The connection between these laws and the critiques of the characteristics of art lies in the balance between protecting individual creativity and acknowledging the subjective and culturally influenced nature of art.

Below is an overview of these laws and their historical origins.

- Copyright law: The concept of copyright law is crucial in protecting artists’ intellectual property. It was formally established with the Statute of Anne in the U.K. in 1710, aimed at regulating the burgeoning printing industry and safeguarding authors’ rights. The function of copyright law is to grant artists exclusive rights over their creations, allowing them to control the use, reproduction, and distribution of their works. This legal framework recognizes artistic originality and effort, providing a means to protect against unauthorized copying or plagiarism. It ensures that artists retain control over their work, thereby encouraging continued creative activity and the proliferation of new art.

- Fair use and fair dealing: Fair use and fair dealing doctrines emerged in the 20th century, evolving as a necessary counterbalance to copyright law. These doctrines were developed to allow some use of copyrighted material without explicit permission for specific, typically non-commercial, purposes. Their function is to permit limited use of copyrighted material for important societal functions like criticism, education, news reporting, and research. This legal allowance acknowledges the vital role of art in culture and discourse, facilitating its analysis, teaching, and broader public engagement. These doctrines connect to critiques about the interpretability and cultural context of art, highlighting the dynamic interaction between art and its audience within various cultural settings.

- Moral rights: Moral rights focus on the personal and reputational connection between an artist and their work. They have their roots in French law, specifically the concept of “droit moral.” These rights have been recognized and incorporated into international law, notably in the Berne Convention. Moral rights include the right of attribution, ensuring artists are recognized as the creators of their work, and the right of integrity, which protects artworks from derogatory treatment that might harm the artist’s reputation. These rights are especially pertinent in relation to critiques of art concerning the artist’s intention and the authenticity of the artwork, emphasizing the deep connection between creators and their creations.

What are the laws against plagiarism of replicas?

Laws against the plagiarism of replicas are designed to address the complex issue of copying or replicating original artworks. These laws are intertwined with the broader legal framework protecting intellectual property and artistic creations. Here’s an overview of these laws and their historical origins.

- Copyright law and replicas: Modern copyright laws typically safeguard original works of art, but protection for replicas is variable, contingent on factors like the degree of originality and the artistic creativity involved in their creation. This nuanced approach mirrors ongoing debates about originality in art, highlighting the complex relationship between an artist’s unique creation and the broader cultural and historical practices of art reproduction. These laws serve to balance the recognition of individual artistic contributions with the traditions of replicating and reinterpreting existing art.

- Trademark law and artistic replicas: Trademark law (evolving in the late 19th century) focuses on protecting symbols, names, and slogans that identify goods and services, and its application has extended to the realm of art to guard against the unauthorized reproduction of replicas. This aspect of law comes into play particularly when replicas are commercially produced and sold, ensuring that such reproductions do not infringe upon trademarks associated with the original artist or institution. This legal framework relates to broader discussions about the impact of commercialization on art, delving into how market dynamics can influence the perception of artistic value and authenticity. Trademark law’s role in the art world underscores the tension between protecting the artist’s intellectual property and navigating the commercial aspects of art distribution and consumption.

- Moral rights and replicas: Moral rights safeguard the personal and reputational relationship between artists and their works, a concept now globally recognized through agreements like the Berne Convention. These rights become particularly pertinent in instances where replicas may negatively impact the original artist’s reputation or distort their intended artistic message. The emphasis on moral rights reflects concerns about maintaining the integrity of an artist’s vision and reputation, aligning with critiques that stress the importance of the artist’s intention and the authenticity of the artwork. This legal perspective underscores the significance of respecting the personal connection between creators and their creations, even as their works are replicated or reinterpreted.

- Laws on reproduction and public domain: Artworks may eventually enter the public domain (typically a set number of years after the artist’s death), at which point copyright protections cease, legally permitting the reproduction of replicas without infringement. This transition of artworks into the public domain touches upon how art is influenced by cultural and historical contexts. Once in the public domain, reproductions can facilitate broader public access to art and contribute to cultural heritage. However, this also raises questions about artistic originality and the potential for commercial exploitation. The movement of art into the public domain reflects the evolving nature of art’s role in society, balancing the preservation of artistic legacy with the opportunity for cultural dissemination and reinterpretation.