We all think we’re pretty smart. Ask anyone what they want in a mate and they’ll tell you: Brains, beauty, and sense of humor. Most of us don’t realize that someone smart, funny, and pretty isn’t interested in us. Because we are, in fact, spectacularly stupid. It’s not our fault, we’re mere meat. Sadly, meat isn’t good at critical thinking. Start an argument with someone and you’ll quickly start making stupid mistakes. Because we’re wired to win, to protect our ego and outlook. We’re built to fight dirty, and that ain’t pretty. It means we do a lot of dumb things.

The stupidest things we do are what is known as “logical fallacies.” These are all things we do during an argument, discussion, or meeting of the minds. They are each mistakes that look like reason on the surface. But they aren’t logic. These aren’t rational arguments. They’re wrongheaded, manipulative, emotional moves that we all make. Each one is designed to derail a fight, not win a contest based on merits and intellect. When you’re really ready to get smart, and ready to fight with your mind, here’s the 13 logical fallacies you need to avoid.

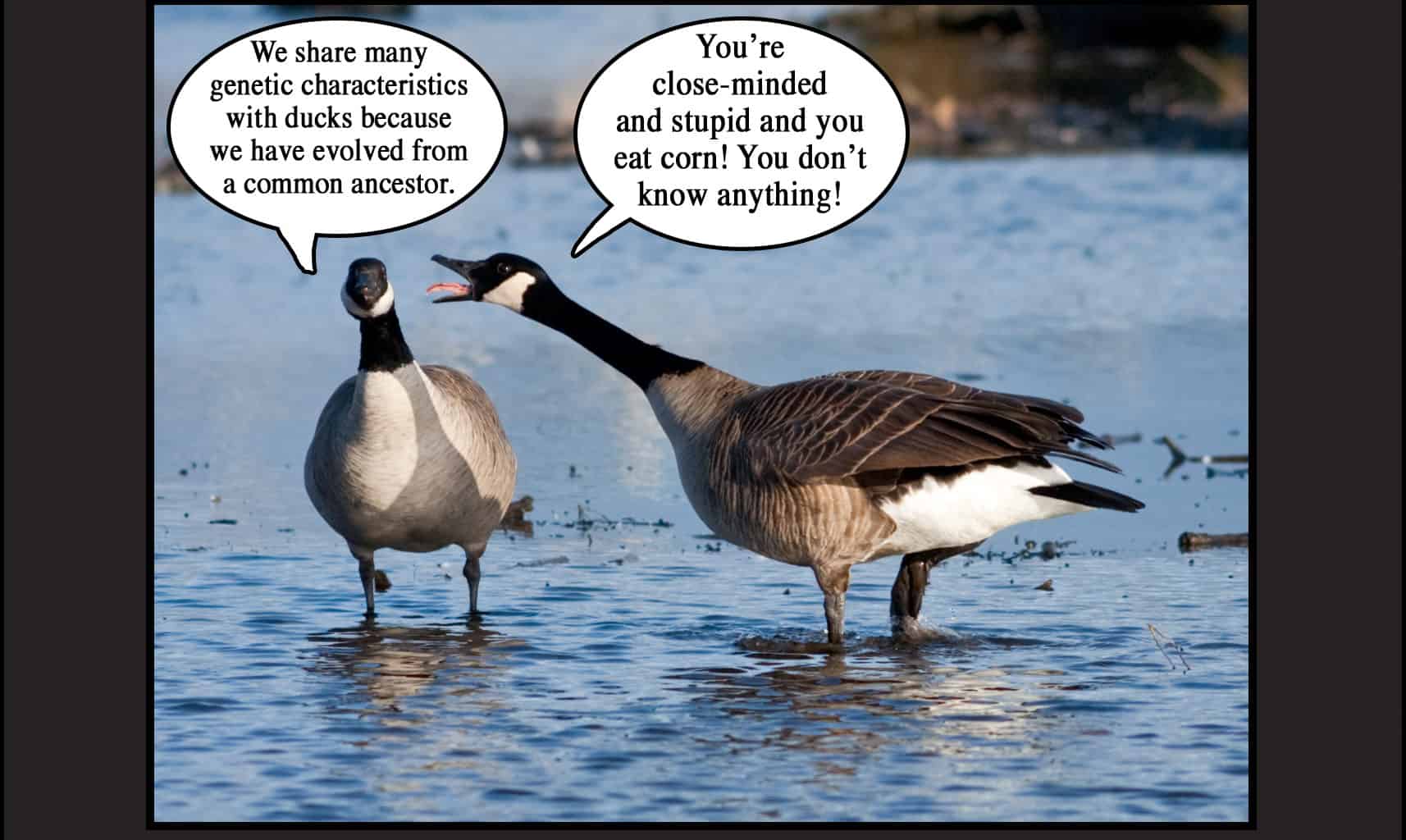

Ad Hominem

This is a common political maneuver where you attack a person, rather than an argument. The assumption is that if you discredit the source, you discredit the point. That’s completely false. Even a completely “wrong” person can make a valid point. Automatically attacking someone, rather than the idea they present, shows you can’t counteract their idea.

Arguing from Authority

This is often the opposite of an Ad Hominem attack. Rather than going after the person making a claim, you claim to know better because you have greater “authority.” This is often what happens when someone points to their job as evidence. “I think I would know. After all, I am an attorney.” doesn’t actually mean anything. A person might be correct, and they might have additional information thanks to their job, habits, or hobbies. That doesn’t add validity to their argument. A bad idea is a bad idea no matter who it comes from.

Ad Baculum

This is similar to an argument from authority, as it is an argument backed by fear. “Agree with me or I’ll hurt you” is how this argument is phrased. Sometimes it isn’t that direct, such as “Love god or you’ll go to hell.” The threat might not be caused by the person making it, but it changes perspective through vague fear, rather than reasoning.

Speaking in Totality

This is a simple mistake to spot. Anytime someone starts saying “always” or “never” or speaking about “all people” or “most people” they’re making huge, HUGE assumptions that are automatically untrue. Nothing “always” or “never” happens, and claiming that “most people” or “a lot of people” think a certain way is inaccurate for a few reasons. The most obvious being: This person is making a point with grandiose language.

Bandwagoning

As with speaking in totality, where you only pay attention to extremes, there’s bandwagon appeals. This is essentially peer pressure to join with everyone else. It doesn’t make an argument better to say more people do it. In fact, it’s right up there with “if all your friends jumped off a bridge…” but it still works. No one wants to be left out, and this claims that by not joining up you’re not on the team. It dovetails with speaking in totality by notions like “if you’re not with us, you’re against us.” As if there are only two sides.

False Dichotomy

Saying things ‘must’ be one way or they ‘must’ be another is a huge failure in arguments. Nature vs. Nurture is a good example of a fake dichotomy. It’s not one or the other, but a combination of both that plays into the totality of the world. Plus, there’s many factors outside of the two diametrically opposed forces. “Love vs. Fear” is another that comes up frequently. These assume zero sum games where you must be subtracting from one side to feed the other. The world is bigger than that.

Arguing from Confusion

This is a great one, as it posits you’re right because no one knows the answer. “Why not believe in the Dharma? No one knows it doesn’t work.” Common in religion, this wrongheaded approach says that no one knows the answer, which makes any answer as good as any other. Not knowing about God or Hell or aliens doesn’t mean any of the above are or are not true. Pointing at nothing and saying it means something is nothing short of insane. Yet, we do it all the time.

Circular Reasoning

Most arguments between couples fall into this category. Here, you’re using your own logic to support your argument in an endless cycle. It works well with arguing from confusion. “If you wouldn’t do X I wouldn’t do Y. And you wouldn’t do X if I didn’t do Y.” is one of the most common arguments. It absolves the person of responsibility, constantly referring back to another idea. “Allah is real because the Koran says so, and the Koran says so because it is true.” is another example. One thing points forever to another, creating a loop.

Confusing Correlation with Causation

Many things happen all at the same time. Sometimes one thing causes another. It snows, and the ground gets wet. That’s one thing causing another. However, assuming that one thing leads to another isn’t always correct, which is where superstition comes from. Think of sports fanatics who believe they must wear a jersey, must eat out of a bowl, must perform a ritual or their team will lose. It’s controlled madness to say that the Seahawks’ terrible performance was the fault of Jimmy who didn’t drink out of the right side of the glass.

Straw Man

A straw man argument is when you create a false analogy, and then destroy that analogy. “Meat is not murder” is an example of a straw man argument. Eating meat is still killing another creature for food. Merely because it isn’t killing one of your own kind doesn’t make it less of a slaughter. It merely means most of the human race is on board with ignoring the bloodshed. To say one thing is like another when that isn’t entirely true – comparing people to Hitler or groups to the Nazis are prime examples of this – is the Straw Man at work.

Observational Selection

A pretty simple mistake, this is when we pretend the bad things that don’t support our argument don’t exist. “The drug saves lives!” might be true, but if it’s only saving a single person while making hundreds of others extremely sick, it’s still not good. You’re speaking partial truths with this one, which is another name for it.

Non-Sequitur

AKA a Red Herring, this is when you throw a spanner into the works to derail an argument. The goal is to distract or change the narrative, since you’re unable to make your point. Quick subject changes such as “Forget about our issues. Look at Dave and Shelia! Those people are really a mess!” stops a fight and redirects it. Hoping no one will notice.

Slippery Slope

An extremely common one where we assume correlation between events, “Legalizing marijuana will lead to legalization of all drugs. And prostitution. And then all the laws will disappear.” Like a Straw Man where correlation and causation have been mixed up, the slippery slope assumes that Q must eventually follow A, B, and C. Only true causation can force one thing to follow another. A, B, and C might lead up to Q, but only if you want the sequence to go that way.