Let’s face it, it just feels good to buy organic coffee. After all, the packaging is always attractive, and they write the nicest blurbs on the back. Instead of subsidizing Coffee Inc. (and slave labor) with your purchase, you can save the planet and enjoy a fresher cup of coffee straight from the hands of artisans living in the deepest jungles or the highest mountains – you need only buy organic!

View in gallery

Well, today we’re putting these virtuous claims to the test. Is organic coffee really organic, or is it mostly just marketing? Find out below whether you’re getting your money’s worth – or if you’re just making somebody rich.

Our critical approach to organic coffee

As with any popular product, there’s a certain vocabulary generally used to sell organic coffee.

Below, we consider three of the most common coffee labels to ascertain whether they really do yield a healthier, tastier, more responsible cup of joe – or whether they’re just feel-good buzzwords.

1. “Organic” coffee

Organic is a venerable label with a lot of baggage. We’re not here to dismiss or promote it, but to educate you on what organic is – and what it isn’t.

Let’s start with something of an eye-opener: Within the letter of US law, “organic” doesn’t actually guarantee the integrity of your coffee. In other words, organic coffee is not, by default, safer or healthier to drink than non-organic brands.

Instead, that coveted organic label narrowly defines a few factors:

- Coffee growers must only use organic fertilizer – no synthetic stuff like potash, rock phosphate, ammonium nitrate, etc.

- No inorganic chemicals must be used in the three years leading up to the harvest of a coffee crop.

- Growers, roasters, and importers must adhere to an “organic plan” overseen by USDA-approved certifying agents, which examines the entire production process and prohibits the use of genetically modified crops.

It seems pretty environmentally responsible on the surface, but there are loopholes to consider.

View in gallery

Exceptions, loopholes, and the question of integrity

First, the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 makes provisions for a “National List”, granting exceptions to certain synthetic chemicals during the growing phase. This isn’t necessarily nefarious, as each chemical must be vetted for human health before inclusion on the list.

But, it does immediately cast doubt on manufacturer claims that their coffee beans are indeed grown in 100% organic soil. To reiterate the point: organic producers are allowed to use certain synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

Yes, these compounds are ostensibly safe. But they certainly fall short of the popular understanding of what organic farming entails – and marketers definitely take advantage of that. Take absolute claims of purity with a grain of salt.

The National Organic Program

To administer and enforce the standards set by the OFPA, the USDA created an agency and regulatory body known as the National Organic Program. The NOP has a three-pronged function:

- Defining and clarifying standards furthering the plain-language, generalized rules of the OFPA to fit real-world applications and scenarios;

- Accrediting agents who will certify whether a company is compliant with NOP standards, both domestically and abroad;

- And, enforcing compliance.

There have been and continue to be a few issues with the NOP in practice, however.

Accreditation loopholes – “Who watches the watchmen?”

You’d probably assume agents accredited by the NOP to hold an advanced degree, extensive experience in the organic agricultural industry, or both. You’d also expect them not to hold any conflicts of interest which could influence their decision on who they’ll give the organic certification to.

Surprisingly, this isn’t always the case. Certifying agents don’t even have to be part of the US government. They can be private individuals or entities, and they don’t even have to be American.

In fact, the USDA has specifically not followed through establishing a peer-review committee to vet applicants, even though the OFPA specifically allows them to do so.

(When attempting to find a source to back this claim, we found that the link to the audit on usda.gov went to a 404. Luckily, it’s hard to remove things entirely from the Internet. Here’s an archived snapshot of the 2010 audit of the USDA by the Inspector General, report 01601-03-HY. Shady.)

We’re not going to delve into speculation as to why this seemingly basic step hasn’t been taken to ensure the integrity of the organic label. But the point is, they haven’t, and the lack of transparency is unsettling.

Also worth thinking about is the fact that food producers – including coffee growers – will often approach multiple certifiers to hedge against the possibility of one denying them that coveted, premium organic label. If the process of vetting was airtight and the standards rigorously upheld, there wouldn’t be the perception that different certifiers would yield different verdicts.

The organic status quo challenged – Harvey v. Veneman

Moreover, there’s precedent for the USDA overstepping the authority granted them by Congress. In the 2003 lawsuit, Harvey v. Veneman, the court found the USDA had wrongfully permitted non-organic chemicals in the processing and handling phase of crop production, thereby undermining the integrity and standards of the organic label.

There was a laundry list of other complaints which were upheld by the courts. Yet the ruling was overturned with an amendment to the OFPA by congress in 2005. The grievances about synthetic chemicals and USDA overreach were retroactively legitimized.

Standards weakened by a rushed, reactionary Congress

Critics have pointed out that this action by Congress eroded the standards of the OFPA. Indeed, the National List of exempt non-organic compounds was voted in only with hesitation by the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB). It passed under the assumption that these chemicals would be removed from the list within 5 years, barring new evidence to prove their food safety.

The 2005 OFPA Amendment changed that assumption, allowing existing loopholes to become even looser. It even introduced leeway for the USDA to greenlight non-organic components in food production absent any “commercially available” organic alternative. Problem is, Congress failed to specify the mechanisms by which the NOSB will determine commercial availability, leaving it open to interpretation – and abuse.

USDA budget cuts

It could be easy to call corruption shenanigans at the USDA. But negligence and lax standards can, at least in part, be explained by aggressive budget cuts over the years. And this isn’t something endemic to one side of the political aisle, either; “Big Ag” is a popular bipartisan whipping boy for deficit hawks of all stripes and feathers.

The lack of resources makes it difficult enough to supervise USDA certification agents domestically – and the problem only compounds with NOP agents abroad. Deadlines get stretched as staff is overwhelmed with the sheer gravity of ensuring 350 million+ Americans have access to safe, affordable food, as well as information enough to correctly identify it amidst a crowded marketplace.

And remember, the legislation controlling “organic” is old and feeble in the face of rising globalism. With political deadlock making actionable compromise ever more difficult, governing bodies are understandably slow to respond to rapidly developing challenges.

“A day late and a dollar short” might be a good slogan for the USDA.

Tricky labeling on organic coffee

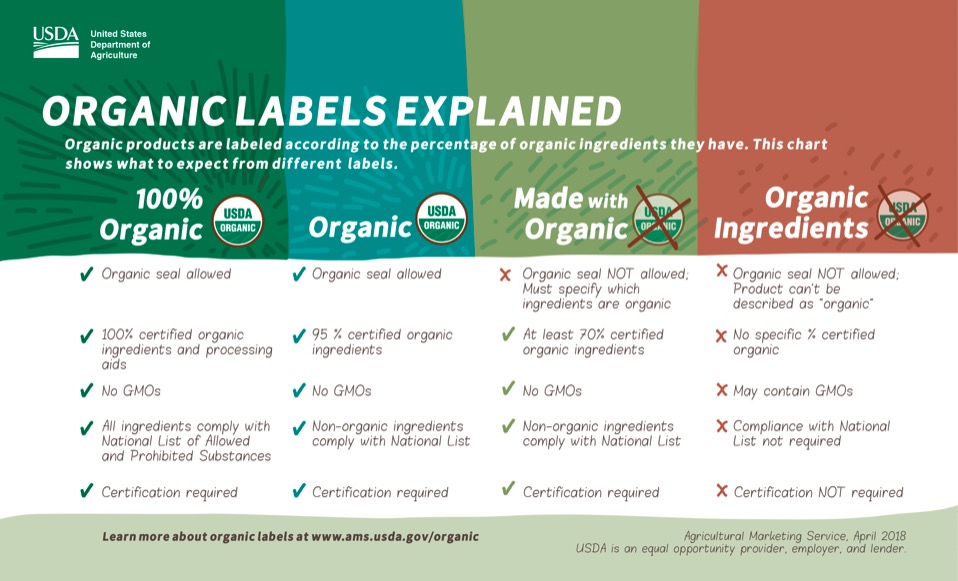

View in gallery

Going beyond politics and possible backdoor dealing, the organic label itself is fraught, leading to confusion in the marketplace. There are actually several tiers of organic-ness:

-

100% Organic

Coffee with this label was grown, processed, and handled with 100% all-organic ingredients. It adheres to the highest standards (such as they are), and justifies the premium price.

-

Organic

No, this isn’t just a catch-all; it’s a specific designation for coffee which contains at least 95% organic ingredients. The remainder of non-organic ingredients must appear on the National List of exemptions. Usually, the beans themselves will still be what we commonly understand as organic, but that 5% falls out somewhere between fertilizing, pest control, and processing.

You’ve gotta be careful here though if you’re searching exclusively for the highest quality coffee. Brands can still proudly display the same “USDA Organic” badge as 100% organic coffee. And you better believe advertisers are going to minimize that missing 5%! It’s probably still going to be tasty, healthy coffee, but that National List might make some think twice.

-

Made with Organic

This is where any doubts about the USDA and its myriad loopholes, oversights, and exemptions will start to compound. Made with Organic coffee won’t have the “USDA Organic” badge, but still contains ≥70% of ingredients which are up to NOP standard.

Made with Organic packaging will really hammer home the feel-good verbiage. You’ll read about how the company is socially just and supports Fair Trade, artisanal practices, and family heritage.

This tier does still require certification from an NOP agent. And while it probably won’t command absolute top-shelf prices, coffee producers still have to offset the often considerable costs of the certification process. It may or may not be worth it to you.

-

Organic Ingredients

This lowest tier makes no solid promises of being legally organic. It may or may not contain GMOs, use synthetic compounds, or be handled and processed in non USDA-approved way.

Nevertheless, you may still find these brands advertise what virtues they can with some creative writing. You should expect not to pay organic prices for this stuff.

That said, it might not be fair to write this tier off altogether. Here’s why…

Non-organic growers may still follow organic practices

As we illustrated above, the US government has been proactive in (more or less) rigidly defining “organic”. However, the certification process itself is often a barrier to small coffee growers in poorer countries.

In many cases, these growers lack the funds to buy into chemical pesticides and fertilizers. They’ll operate at a smaller scale by default, often employing family and members of the community. For all intents and purposes, these “passive organic” sources embody what we commonly understand as the organic, clean, natural ideal.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that is or isn’t the case; it’s just evidence that the situation is complex. And yes, despite the lack of USDA Organic certification, these products still make it to market in the US.

When covering the various tiers of organic in the previous section, we were careful to illustrate how branding plays into perception. A lot of it is marketing hype, but sometimes you really are getting coffee from a small family that’s been producing the same delicious roast for generations.

How smallholders get screwed doing the right thing

View in gallery

The unfortunate reality is that “USDA Organic” is something of a double-edged sword. We want the people who are following natural, healthy farming practices to make it to market; to reap rewards for their environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and dedication to a damn-fine cup of coffee. We also want to encourage people to do the right thing and switch over from harmful practices.

But again, the certification process itself is expensive. Small farms will typically pay north of $700, while processors are asked to pony up over $1200. This might not seem like that much, but when you reckon your accounts in quetzals, pesos, or birr, those American dollars quickly become prohibitively costly.

And even if you can get over that hump, you still have to go through the process of conversion. Remember that bit about needing to prove your soil hasn’t seen a drop of (non-approved) synthetic fertilizer or pesticide for at least three years? That’s a long time to dramatically change your production process without having a market handy to compensate for the added cost and lowered production.

One of the higher-profile examples of this phenomenon is Oscar Omar Alonzo, a Honduran coffee farmer who suffered a 90% drop in productivity switching over to organic. He managed to survive the long three years, and found a suitable substitute for chemical fertilizers in the form of moisture-retaining coconut husks. His is a success story, though it’s exceptional in every sense of the word.

Other considerations for non-organic farming

Coffee is a unique crop in many ways. For one, it is grown most harmoniously under shady forest canopies. Yes, it grows slower than it would in direct sunlight, but this allows the beans to mature more slowly and develop a higher density of delicious sugars.

A shade-grown coffee farm exists in greater ecological balance with its surrounding environment. But that biodiversity comes with certain challenges as well. Pests are a natural feature of the forest, and will enjoy “coexisting” amidst coffee crops to the detriment of yields.

Without chemical pesticides, farmers resort to far more labor-intensive measures of pest control. And sometimes, Mother Nature still gets the upper hand, forcing farmers to choose between losing their entire crop, or spraying pesticides or herbicides to salvage their precious lifeline. Complicating the situation further is that NOP certifiers will poo-poo this last-ditch effort, and revoke the farmer’s access to the valuable organic market.

On the other hand, there may be a competing organic coffee farm growing crops in isolated fields under direct sun. Their coffee plants grow fast and yield prodigiously, and it’s a lot easier to keep them alive without risking the farm’s organic certification battling pests.

And yet, the rapidly grown coffee just isn’t as tasty. Moreover, this certified farm doesn’t exist within its natural context. Absent the dense, carbon-sucking foliage, this organic farm is a net emitter of greenhouse gasses. And as the hot sun bakes the soil, farmers must increase irrigation to the detriment of local freshwater sources. There’s also erosion and runoff to consider, as well.

…It almost makes the non-certified shade-grown farm that occasionally sprays fertilizers and pesticides the more ecologically responsible and more consumer-friendly option. The point is, the USDA’s one-size-fits-all certification approach often rewards the more destructive model.

2. “Fair Trade”

Much like “organic”, “Fair Trade” is an ambitiously progressive concept that hasn’t quite kept pace with globalism. While Fair Trade offers another badge of desirability to a given coffee product, it doesn’t enjoy quite the same level of market demand as its “USDA Organic” counterpart.

View in gallery

This is an important distinction, because lower demand creates perverse incentives for democratically run cooperatives of small growers operating on thinner margins than corporate behemoths like Nestlé. It’s a complicated issue, but we’ll try to break it down.

Here’s some perspective: Coffee is the second most valuable trade commodity after oil. It primarily flows from poor countries to rich countries, and the resulting power imbalance has long proven ripe for abuse.

In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, corrupt cartel control of coffee lead to highly volatile price swings. This pretty much ensured no one walked away from the markets a winner. Eventually, several activist organizations formed across Europe to seek more mutually equitable trade solutions between rich consumer and poor producer countries. In 1997, these merged into the Fairtrade Labelling Organization.

This now-massive organization had the power and influence to set standards which sought not only to stabilize the commodities markets, but to ensure producers got their fair shake. Yes, beyond mere self-interest, social justice was and is indeed the driving goal of FLO.

The mechanics of Fair Trade

There are two main ways by which the FLO – via its subsidiary regional arms like Fair Trade USA – enforces fairer trading conditions for smaller coffee producers in poor countries. These are:

- Price floors

- Consumer premiums

Price floors ensure that Fair Trade certified growers and producers always have access to a predictable minimum selling price for their goods. In order to qualify, you must be a part of a democratic cooperative of growers and/or roasters.

This model is important not just for Western ideological reasons; it also ensures that the revenue generated by the consumer premiums (currently $0.20 per pound) levied on coffee sales go towards enriching the people and infrastructure that make sustainable production possible in poor countries. It’s power directly to the people, as the coops make the decisions for themselves where to allocate funds.

And you know what? It has done quite a lot to alleviate or even eliminate poverty in producer communities around the world.

In the past 20 years, overall demand for coffee has reached historic highs. This should be a boon for Fair Trade coffee, but unfortunately it hasn’t quite kept pace with other types of commodity coffee. Here’s how price floors factor into that deflating demand:

The pitfalls of price floors

First, understand that there are several distinct quality grades of coffee, each commanding different prices on the open market. Certified Fair Trade farms can (and usually do) produce multiple grades of coffee, yet they will only find limited buyers at Fair Trade prices due to limited demand.

Now, say the Fair Trade price floor of a bag of organic washed Arabica beans is $1.70. (And it currently is at the time of writing.) Your farm has produced two bags of this coffee, though of different quality. (Maybe you watered or fertilized one crop more than the other, or one side of your field is shadier than the other.)

The lesser bag fetches $1.50 on the open market, while the tastier beans garner $2.00. Of course, both bags – regardless of quality grade – qualify to be sold at the $1.70 price floor. You are a certified Fair Trade farm, after all.

Because Fair Trade coffee is a specialty product with limited demand, however, there’s a buyer for just one of your bags at the Fair Trade price floor of $1.70, leaving you to sell the remaining bag on the open market as an ordinary commodity coffee at a price befitting its grade.

Thus, you are strongly incentivized to sell your lesser-quality bag under the Fair Trade label. Meanwhile, your premium organic washed Arabica commands full price, netting you a nice profit!

So, you plan your next harvest, and decide to cut costs even further on the bag that will get sold as Fair Trade – the price is guaranteed by Fair Trade USA, so what do you care if it doesn’t taste as good? You’re going to reallocate funds to make your premium bean even better.

This perverse incentive is self-reinforcing, unsustainable, and taints the Fair Trade brand.

The problem with premiums

We’ll restate something said earlier: Each bag of Fair Trade coffee effectively has a $0.20 tax on it, which goes directly to the coffee cooperatives that produced it. Of course, individual farmers who are members of those coops actually produced the individual bags, and yet they must all vote on where to allocate those funds.

And it usually isn’t to remunerate the individual growers. In the best case scenario, local medical or educational centers get funded, thereby raising the overall prosperity of the community. Or, crumbling infrastructure is restored, making it more efficient for everyone in the coop to conduct business.

But, it is also ripe for abuse, and the FLO has limited power of oversight. Critics are increasingly pointing out how unfair this practice can be, while proponents of premiums stand by the core ideology behind them. So who’s right?

Well, it’s complicated. Any good solution will require nuance, but there’s a startling lack of data to illustrate the true nature of the problem. Time will tell how effective we are at bringing this model into the 21st century.

So, is Fair Trade a bust?

It doesn’t have to be, and it isn’t always. After all, a lot of people truly believe in what the label stands for, and are willing to resist the temptation of perverse incentives and corruption. This also means that it is perfectly possible to find a delicious bag of Fair Trade coffee. Just beware that it will require trial and error, and always at a premium.

3. “Single Origin”

The latest craze in coffee is Single Origin, which is defined as coffee grown, produced, and imported from a single source. It might all come from one country, or it could be as granular as single coop or farm.

View in gallery

Typically, Single Origin branding will feature the smiling faces of actual human beings. You’ll learn their names, family histories, and hear stories of inspiration, artisanship, and perseverance. You might even learn about the exact microlot your brew came from, complete with pictures, soil facts, and educational reports on other relevant environmental and production factors.

Given the controversy and confusion surrounding the “Organic” and “Fair Trade” labels, it’s not hard to understand why Single Origin is in vogue. It allows the coffee to really speak for itself, and empowers low-information consumers (i.e. not deeply versed in the complexities of international coffee markets) to identify, connect emotionally with, and buy into quality coffee.

How it all comes together for coffee lovers

Single Origin, Organic, and Fair Trade are also by no means mutually exclusive. There’s a ton of room for overlap, and building awareness of these points of intersection can help you reap greater enjoyment and satisfaction of coffee, without overspending.

And despite the controversies and misinformation, people are more passionate about coffee than ever – whether they’re producers, promoters, or consumers of this magical black liquid. There’s no lack of deep-dive reviews, grower profiles, thought pieces, and even hard socio-economic analyses to guide your discovery.

We recommend you start your search for the perfect you-brew by going broad first, then deep later. BrewSmartly wrote a great piece concisely reviewing a smorgasbord of 10 modern organic coffee brands. Give it a quick look, keeping in mind what you’ve learned in this article to help you discern helpful information from hype.

Just How Organic Is Organic Coffee? CONCLUSION

If you’ve ever wondered “just how organic is organic?”, we hope today’s article has helped provide some clarity on the matter. In order to get a holistic understanding of the humble coffee bean and its impact on humanity, we’ve taken a critical look into the three most common labels used to differentiate and sell coffee: Organic, Fair Trade, and Single Origin.

Our purpose is to neither endorse nor damn the industries surrounding these keywords, but to educate you that they’re more than just empty buzzwords.

Did you learn something new today? What factors into which coffee you buy and drink at home, the office, or out and about? Do you have a favorite brew we’ve absolutely got to try? Sound off in a comment below!