The Erikson psychosocial theory explains personality development over the course of a lifetime as shaped by a series of psychosocial conflicts. The psychosocial development theory was first published in 1950 by German-American psychologist and psychoanalyst Erik Erikson in his book, The Eight Ages of Man. Erikson formulated his theory based on observations during psychoanalytic research and while practicing as a psychoanalyst, with the basis of his ideation stemming from Freudian theory.

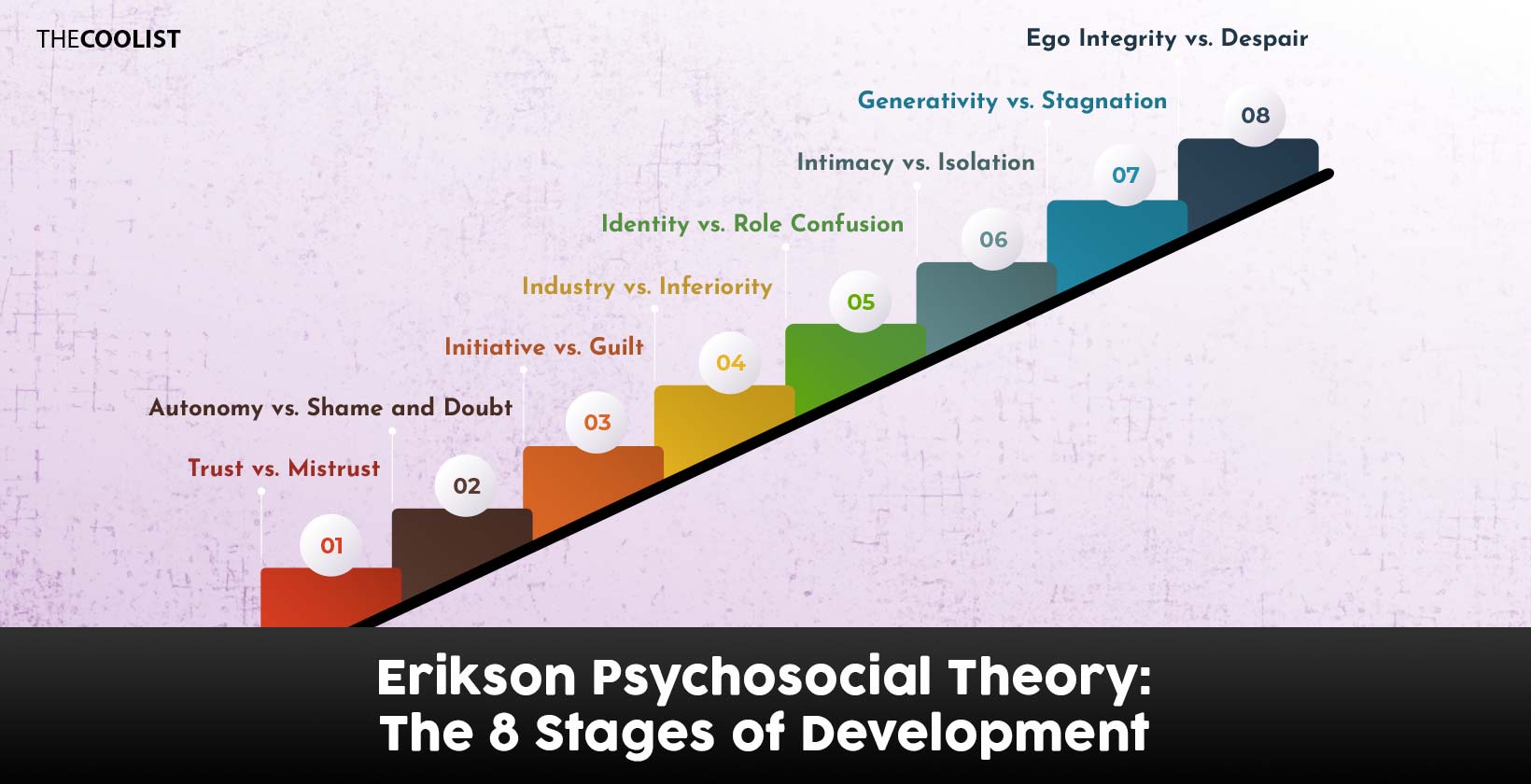

Erikson’s theory of development comprises eight sequential stages, spanning the entire lifetime of an individual from birth until death. Each of the eight developmental stages is characterized by a psychosocial conflict between two extreme attitudes. Negotiating each conflict and learning to balance between the extremes helps the individual attain a specific virtue, which in turn helps form the person’s identity. A person’s ability to resolve the psychosocial conflicts along their developmental path hinges on the influence of their family, friends, and society as a whole. The family helps a child navigate the earliest Eriksonian stages and attain a sense of independence, adequacy, and purpose. The family additionally passes down its set of moral, political, religious, and cultural beliefs to the child, all of which become part of the child’s identity. Friends begin to play a role in one’s conflict resolution and development progression during the school years, and their influence culminates during one’s identity crises, which happen in the teens. Society’s role in the formation of a person’s identity is threefold, as the individual navigates through societal values, gender and occupational roles, and the socially imposed purpose in life.

Erikson’s theory has been mainly criticized for limiting each psychosocial conflict to a very specific period in the life of an individual. However, the Eriksonian development theory continues to be used as a tool in psychological research and in psychiatric clinical settings.

Below is an overview of each of the eight stages of Eriksonian development theory, the associated psychosocial conflicts, and their influence on the formation of an individual’s identity.

What are the stages of Erikson’s Personality Theory?

Below are the eight stages of Erikson’s personality theory.

- Trust vs. mistrust: The trust versus mistrust stage occurs between birth and 1.5 years of age. This critical stage comprises the development of the child’s trust, thus laying the foundation for the future evolution of the personality.

- Autonomy vs. shame and doubt: The autonomy vs. shame and doubt stage takes place between 1.5 and 3 years, just as the child learns to be independent. Encouraging independence and the exploration of interests at this stage helps the child develop their power of will.

- Initiative vs. guilt: This stage spans the period between 3 and 5 years of age and is characterized by the child’s evolving decision-making abilities. Allowing children to make decisions helps instill a sense of self-confidence in them as they mature.

- Industry vs. inferiority: The industry vs. inferiority stage of development happens between 6 and 12 years of age. The child begins to judge their competencies in relation to those of their peers, a process that may spur feelings of adequacy and inferiority.

- Identity vs. role confusion: This stage occurs during adolescence, spanning between 12 and 18 years of age. The identity vs. role confusion stage is characterized by the teen’s exploration of their own identity and learning to accept others’.

- Intimacy vs. isolation: The intimacy vs. isolation stage is the primary phase of a person’s adult development. This stage is marked by the expansion of one’s horizons beyond themselves, beginning to care for others, and experimenting with intimate relationships.

- Generativity vs. stagnation: This phase takes place between 40 and 65 years of age. People in this stage are well-advanced in their careers, have established interests, and spend a good portion of their time raising children. This stage brings out either generativity or a sense of uselessness in people.

- Ego integrity vs. despair: Ego integrity vs. despair happens after a person reaches their 65th birthday. The stage is characterized by the need to accept one’s life’s achievements and failures. The ability to take such revelations in stride leads to wisdom, whereas a rejection of one’s course of life results in despair.

Below is a more in-depth overview of the eight stages of development in Erikson’s theory, as well as their associated virtues and psychosocial conflicts.

1. Trust vs. mistrust

The first developmental stage in Erikson’s theory is defined by the trust vs. mistrust psychosocial conflict, and happens during infancy, from birth to the age of 1.5 years. This is the stage in which a child learns to have basic trust in their caregivers, and eventually, other people. The child relies on parents, and notably on the mother during this phase, and learns to trust or mistrust based on the maternal relationship. The mother’s trustworthiness reflects on the baby. Receiving loving care during this stage builds a sense of trust in the child so that the child is able to have faith in authority figures other than their parents.

The trust vs. mistrust stage is fundamental to the development of a human being, according to Erikson’s theory, as the ability to trust eventually molds a child’s identity. Failure of this developmental stage leads to a fear of unpredictability that in turn shapes subsequent developmental phases. Success at the trust vs. mistrust stage depends largely on the actions of the child’s parents. Affording the child plenty of care, love, and devotion promotes trust, while inattentive and careless parenting breeds mistrust. This progression develops the virtue of hope in children, according to Erikson.

2. Autonomy vs. shame and doubt

The psychosocial conflict of autonomy vs. shame and doubt defines the second developmental stage of Erikson’s theory. The autonomy vs. shame and doubt stage lasts during toddlerhood, between 1.5 and 3 years. The child gains basic independence at this stage, as they learn to self-perform simple tasks. This agency leads the child to crave greater autonomy, which develops a sense of confidence and independence if encouraged by the parents.

Parents have an outsized role in the child’s success at this formative phase. Giving children agency, allowing them to explore interests, and welcoming successes and failures alike helps the child develop a sense of independence, confidence, and self-esteem. On the other hand, discouraging children from doing things on their own and criticizing their blunders impedes the child’s progress through the autonomy vs. shame and doubt stage. An unsuccessful progression through this phase leaves children with a sense of self-doubt and fear of failure. Erikson’s theory claims that successful resolution of the autonomy vs. shame and doubt conflict builds the virtue of will in the individual.

3. Initiative vs. guilt

Initiative vs. guilt is a psychosocial conflict that lasts throughout a child’s preschool years, between the ages of 3 and 5. The initiative vs. guilt phase is characterized by the child’s growing desire to make decisions. Having the ability to decide cements a child’s independence and starts to build their leadership skills.

The initiative vs. guilt phase of development takes its shape in the child’s interactions with their caregivers and their peers. The parents are able to nurture their kids’ critical thinking skills and teach them to take initiative by encouraging them to make autonomous decisions. Successful progression through the initiative vs. guilt stage allows a child to take on a leadership role among their peers, a characteristic that continues to evolve well into adulthood. In contrast, criticizing kids’ decisions or discouraging the independent thought process breeds a sense of guilt in the kids, who are more likely to become followers than leaders. Erikson’s theory states that successfully resolving the initiative vs. guilt conflict results in the emergence of the purpose virtue in the person.

4. Industry vs. inferiority

The industry vs. inferiority psychosocial conflict defines the fourth stage of development in Erikson’s theory. The industry vs. inferiority stage occurs between ages 6 and 12, coinciding with the Freudian latency stage. This phase of an individual’s development involves a self-assessment of one’s capabilities in relation to peers. The child begins to compare their competencies to those of their classmates, and social circles begin to expand and influence behavior.

The industry vs. inferiority stage of development is impacted by the child’s interactions with peers, teachers, and parents. The child may develop feelings of either confidence or inferiority as they measure their abilities and successes against those of their peers. It is up to the teachers and parents to reinforce successful outcomes, welcome failures, and instill a sense of confidence in the child. A successful progression through the industry vs. inferiority phase leads to the child to develop a sense of adequacy. Meanwhile, negative feedback from teachers or parents ignites and reinforces a sense of inferiority in the child. Navigating successfully between the two opposite outcomes of the industry vs. inferiority complex develops the individual’s competency virtue, according to the Erikson theory.

5. Identity vs. role confusion

Identity vs. role confusion is the psychosocial conflict shaping the fifth Eriksonian development stage. This stage lasts throughout one’s adolescence, between the ages of 12 and 18. The psychosocial conflict at the heart of the fifth development is characterized by the teen’s longing to understand their identity. According to Erik Erikson, the two prominent identities a teen is trying to establish during this phase are sexual and occupational. The teen may experiment with different roles in the course of this phase, and become more open to the influence of their peers. At the same time, most adolescents shift away from their parents’ influence at this time. This shift happens as the teen begins to value social interactions and has a strong desire to fit in with their friends. The identity vs. role confusion phase additionally entails the teen learning to accept their peers’ identities and beliefs while still formulating their own.

Success and failure at the identity vs. role confusion stage are largely shaped by the teen’s social interactions in three ways. Firstly, belonging to a group of friends helps reinforce the teen’s sense of identity, whereas feeling marginalized causes confusion and complicates identity formation. Secondly, exposure to diverse beliefs, ideas, and identities molds the teen’s system of moral, political, and religious beliefs. Thirdly, support and mentorship from the teen’s parents and teachers are paramount in reinforcing their identity formation. A lack of mentorship, or excessive pressure from authoritative roles in the teen’s life leads to uncertainty in their purpose and identity confusion. Learning to balance between identity formation and role confusion leads to the emergence of the fidelity virtue in the individual, according to Erikson.

6. Intimacy vs. isolation

The intimacy vs. isolation developmental stage is the first phase of adulthood according to Erikson’s theory, and it lasts from 18 to 45 years of age. The stage revolves around the conflict between one’s need to form intimate relationships and their struggle to do so successfully. Young adults entering the intimacy vs. isolation stage have lingering effects from the identity vs. role confusion stage and are thus continually trying to find their place in society. One’s urge to establish deeper relationships becomes a new aspect of this search. These relationships may or may not be romantic, but either way, they require the individual to make certain sacrifices in order to establish a meaningful, intimate connection.

Individuals who enter the intimacy vs. isolation stage with firmly established identities are generally more successful in resolving this psychosocial conflict, as they have a better notion of who they are, what they want, and how they’re willing to compromise for the sake of another human being. Success at the intimacy vs. isolation stage is additionally likelier if the individual is ready to compromise with others and has overcome their fear of intimacy in forming relationships. In contrast, those who fear intimacy may try to self-isolate during this early phase of adulthood in order to protect their egos from what they perceive as the inevitable pain of rejection. Learning to find an equilibrium between the two extremes of intimacy and isolation fosters the virtue of love, according to Erikson.

7. Generativity vs. stagnation

Generativity vs. stagnation is the social conflict at the center of the seventh Eriksonian developmental stage, which spans one’s middle adulthood, between 45 and 64 years. Middle-aged adults in this stage navigate between a desire to help and guide the new generation and a dissatisfaction associated with a self-centered existence. An individual at this stage has the opportunity to assume a mentorship role in their family and professional lives while helping aging parents and finding harmony with their partner.

A successful progression through the generativity vs. stagnation conflict entails finding purpose by committing oneself to the improvement of society. Adults in their middle ages contribute to society by continuing to mentor their children while giving them more autonomy over life choices, accepting their partners, and helping out with raising grandchildren. Additional tasks that allow a middle-aged adult to progress through their psychosocial conflict include taking on civic responsibility, adopting healthy lifestyle choices, and finding productive means of spending their leisure time. Unsuccessful resolution of the generativity vs. stagnation conflict generally stems from one’s aversion to taking an active role in the improvement of society, including the relinquishment of parenting and community duties. Such reclusion from mentorship and leadership roles leads an individual to experience stagnation as they feel their life’s purpose slipping away. Erikson claimed that being able to traverse between the extremes of generativity and stagnation develops the virtue of care in an individual.

8. Ego integrity vs. despair

The ego integrity vs. despair is the psychosocial conflict characterizing the eighth and final stage of development according to Erik Erikson. The ego integrity vs. despair stage spans the later adulthood, from the age of 65 and up. Adults in this stage are retiring and discontinuing many routine tasks. Increasing amounts of leisure time, as well as a desire to maintain autonomy in the face of deteriorating health and abilities, affect individuals in the ego integrity vs. despair stage in two ways. Firstly, these older adults begin to assess and question the meaning of the lives from which they’re slowly stepping away. This intense period of introspection leads to either a sense of contentment stemming from a purposeful, successful life, or despair from the feeling of living one’s life in vain. Secondly, the desire to preserve autonomy coupled with more free time leads older adults to explore new hobbies and interests. This exploration helps the adult maintain a sense of purpose in their lives.

Success in navigating the ego integrity vs. despair psychosocial conflict hinges on two factors. Firstly, the individual must have had some success in progressing through the previous stages of development. Acquiring virtues throughout the seven preceding stages helps one find greater meaning in their life’s path and accomplishments. Secondly, one must have serenity to take life’s successes and failures in stride, without allowing despair to creep even in the face of regrets or unaccomplished goals. The absence of the two aforementioned factors leaves an individual in despair about a life that went idly by, with nothing to show for it before the curtain falls. The ability to chart a course between the two polar opposites of this psychosocial conflict instills the virtue of wisdom in a person, according to Erik Erikson.

How does each stage help us develop a healthy personality?

Each stage helps us develop a healthy personality by forcing us to experience a psychosocial conflict, progressing through which earns us a new virtue, according to Erikson’s theory. Advancing through the first stage of development lands us in the midst of the trust vs. mistrust conflict, which helps us gain the virtue of hope as we learn to trust our caregiver’s integrity. The second Eriksonian stage of development sees a toddler navigate through the autonomy vs. shame and doubt psychosocial conflict. This conflict pits a child’s burgeoning agency against a sense of self-doubt and shame experienced when caregivers suppress or discourage independence. Moving forward through this conflict instills the virtue of will in a child. In the third stage of development in Erikson’s theory, a preschool child finds their way through the initiative vs. guilt conflict as they learn to make decisions. This conflict teaches the child to make decisions with confidence and fosters the virtue of purpose. The fourth stage of development exposes the child to the industry vs. inferiority conflict, in which they compare their abilities against those of their peers. Successful progression through this stage helps the individual develop the competency virtue. The fifth stage of development forces a teen to go through the identity vs. role confusion conflict, as they attempt to understand their identity while accepting others’. Passing through this stage of development helps the individual acquire the fidelity virtue. The sixth Eriksonian development stage coincides with early adulthood and introduces the individual to the intimacy vs. isolation conflict. One progresses through the sixth stage by learning to compromise with others in the quest to form meaningful relationships. Successful completion of the sixth stage leaves an individual with the virtue of love. The seventh stage of development takes root in the generativity vs. stagnation conflict, during which middle-aged adults begin to transfer their skills to the younger generation. Getting through the seventh stage instills the care virtue in a person. The eighth and final stage in Erikson’s theory spans one’s later years, during which the individual acquires the wisdom virtue as they negotiate the ego integrity vs. despair conflict by coming to terms with their life’s successes and failures.

How can I apply this theory to my life?

You can apply this theory to your life in two ways. Firstly, you can apply the theory behind the adult stages of development (stages 6-8) by focusing on resolving the psychosocial conflict in every stage. In the sixth stage of development, overcoming the fear of rejection and learning to sacrifice yourself in order to form a deep relationship with a friend or partner helps you attain the virtue of love. Completing stage 6 effectively gives you the tools needed for establishing intimate, meaningful bonds with people. In the seventh stage of development, focusing your efforts on bettering society leaves you with a sense of purpose and the virtue of care. Meanwhile, the eight Eriksonian stage of development gives you a chance to face your life’s accomplishments and defeats, as you cultivate wisdom and accept the approaching end. Secondly, you can apply this theory to helping the children in your care overcome the psychosocial conflicts they experience in their developmental stages (1-5). During the first stage of development, you should afford your baby the care and love needed to build their virtue of hope. The second stage of development demands that you encourage your child’s independence and commend their successes as they develop the virtue of will. You should continue to support the child’s decision-making, welcome their failures, and avoid excessive criticism as they progress through the third stage, learning the virtue of purpose. As your child begins the fourth stage, it’s up to you to reaffirm your child’s adequacy and support them as needed while they acquire new skills and knowledge. During the fifth stage of your child’s development, you must allow them to explore their identity while offering subtle guidance: Doing so supports identity formation and prevents the child from rebelling.

What influenced Erik Erikson’s theory?

There are two factors that influenced Erik Erikson’s theory. Firstly, Freudian psychoanalysis theory had an influence on Erikson’s understanding of personality development. Erikson studied Freud’s stages of psychosexual development, which correspond with the Eriksonian stages in the following manner.

- Oral stage: Freud’s oral stage takes place at the same time as Erikson’s first stage of development, and the associated trust vs. mistrust conflict, from birth to 1.5 years of age.

- Anal stage: The anal stage in Freudian theory corresponds with the second stage of development in Erikson’s theory and the autonomy vs. shame and doubt psychosocial conflict.

- Phallic stage: The phallic stage in Freud’s theory coincides with the third Eriksonian stage of development and the initiative vs. guilt conflict.

- Latent period: Freud’s latent period occurs concurrently with Erikson’s fourth development stage and the associated industry vs. inferiority psychosocial conflict.

- Genital stage: The genital stage in Freudian theory happens at the same time as Erikson’s fifth stage, which is characterized by the identity vs. role confusion conflict.

However, the sequential alignment between Freud’s and Erikson’s developmental stages does not mean that the two psychologist’s theories are identical. Freud’s personality theory placed a heavy emphasis on a child’s sexual development, while Erikson paid greater attention to social interactions and other environmental factors, and considered the latter to be more consequential in the formation of personality. Secondly, Erikson’s research and employment as a psychoanalyst influenced his theory of personality development. Erikson worked as a child psychoanalyst in Boston and San Francisco in the 1930s and the 1940s. Additionally, Erikson participated in numerous psychological studies, including studies of children of the Sioux and Yurok tribes and a child development study conducted by the University of California. Erikson leaned on the knowledge he acquired in the course of research and psychoanalytic practice to refine and further the developmental stages conceived by Sigmund Freud.

What is the importance of Erikson’s theory?

The importance of Erikson’s theory is twofold. Firstly, Erikson’s theory is useful in clinical psychiatry. The premise of the Eriksonian development theory helps psychiatric professionals formulate a course of treatment for mental health patients, particularly those at a turning point in their lives. Understanding the environmental forces that surround them in the context of Erikson’s stages helps patients understand themselves, and the external factors behind their illness. Such insights aid the recovery process. Secondly, Erikson’s theory has proven to be reliable and valid in a number of psychological studies. The Eriksonian development stages became the basis of the Modified Erikson Psychosocial Stage Inventory (MEPSI), a tool for measuring an individual’s psychosocial attributes. MEPSI aims to quantify an individual’s level of resolution of each psychosocial conflict associated with the eight Eriksonian stages. A 2004 review of MEPSI use as a study tool in topics such as youth health, parenting, and criminal justice found reliability scores of 0.92-0.96 (with 1.00 meaning “no error”). Meanwhile, separate studies on the adaptation to parenthood and the likelihood of symptomatic experience in individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) have proven the construct validity of MEPSI. Having high scores in both reliability and validity means that MEPSI is an effective tool for gathering empirical data in those contexts in which its reliability and validity were assessed.

What is identity?

Identity is an individual’s sense of self that’s defined by three characteristics. Firstly, identity is defined by one’s physical and physiological attributes. The appearance of one’s body, as well as the unique manner in which one’s body functions, contribute to a person’s sense of self and comprise a portion of their identity. Secondly, identity is defined by a person’s cultural, ethnic, and religious affiliations. A person’s cultural, ethnic, and religious backgrounds often make up a sizable component of a person’s sense of self. Thirdly, one’s identity is defined by their psychological traits. Psychological traits are wide-ranging in their definition, and an individual’s perception of their own traits may differ from that of others’. The formation of a person’s psychological characteristics takes place over the eight stages of development, according to Eriksonian theory. Each of the eight development stages presents an individual with a psychosocial conflict to resolve, and negotiating these conflicts leaves the individual with virtues, maladaptations, and acquired personality traits. A person’s interactions with family, friends, and society as a whole during their resolution of a given psychosocial conflict shape their psychological traits and reflect in their identity.

According to Erikson, identity is the fundamental organizing principle that develops throughout the lifespan of an individual. However, identity is continuous, meaning that an individual believes they remain the same person despite changes in their physical, physiological, and psychological attributes or affiliations.

What is the role of the family in the development of identity?

There are five roles of the family in the development of identity, which takes place throughout the eight Eriksonian stages but is particularly active during the identity vs. role confusion stage. Firstly, the family plays a role in shaping a child’s self-esteem, which comprises a major portion of their identity. The second, third, and fourth stages of development expose children to psychosocial conflicts that test their ability to accomplish tasks. The family’s support is paramount in the child’s developing sense of self-perception as they face their first successes and failures in these tasks. Parents and siblings who greet successes and failures with love and support help their children build self-confidence, which in turn molds their burgeoning sense of self. In contrast, family members who criticize young children’s failures inhibit their kids’ self-esteem development. Secondly, the family has a significant role in their child’s self-perception of being autonomous. Parents who allow children to explore their interests, make decisions, and complete tasks on their own during the first five stages of development promote the kids’ sense of independence. On the other hand, overbearing parents who reign in their children excessively encourage feelings of dependence and subservience in their kids. The child’s sense of self absorbs and builds upon these feelings of autonomy and dependence, and they become a cornerstone component of their identity. Thirdly, the family plays a role in developing the child’s religious, cultural, and political identity. A child is continuously exposed to the culture, religious practices, and political beliefs of their family members throughout the first five Eriksonian development stages. Upon reaching adolescence, a child begins to reconcile family influences in these aspects with the identities of their peers. The teen begins to wonder whether or not they align with the beliefs and traditions in which their family has brought them up and those of their peers. Ultimately, these influences may or may not become a part of the child’s identity. Fourthly, the family influences an individual’s professional identity, a process that begins in the earlier stages of development and culminates in the identity vs. role confusion stage. Children who view their parents as role models may take an interest in their careers, an interest that becomes more serious as childhood turns to adolescence and the individual approaches the working age. Conversely, a child may feel repulsed by their parents’ career choices, particularly if the mother and father show displeasure with their jobs at home. In some instances, parents may pressure their children to pursue specific careers, and the children may bow to these pressures or rebel. Fifthly, the family plays a role in shaping one’s sexual identity. Biological gender, gender role, gender identity, and sexual orientation are innate, but a person may or may not accept these parts of their sexual identity in an attempt to conform with, or rebel against, familial expectations.

What is the role of friends in the development of identity?

The role of friends in the development of identity revolves around self-discovery. The fourth Eriksonian development stage (industry versus inferiority) forms the basis for a child’s exploration of the self. The pre-adolescent child begins to measure their competencies against those of their peers. This quantification process allows the child to self-identify as being able or unable to perform various tasks. The development progresses, setting the stage for further introspection based on interactions with friends. The fifth stage of development exposes the adolescent individual to the identity vs. role confusion psychosocial conflict, during which their friends continue to propel the self-discovery process. The teen attempts to gain social acceptance among their friends, and in the process, starts comparing friends’ physical and psychological attributes against their own. The adolescent individual additionally attempts to reconcile the cultural, religious, and political values with which they’ve been brought up with those of their peers. The subsequent development stage (intimacy vs. isolation) compels the young adult to seek deeper connections with friends and romantic partners, and the influence of friends continues to affect their identity formation. The young adult may pivot in some of their core beliefs due to influence from a new group of friends. Morals, ethics, and beliefs continue to evolve throughout one’s lifetime, as the individual experiences different interactions with their friends.

What is the role of society in the development of identity?

The role of society in the development of identity is threefold. Firstly, society transfers its collective beliefs, values, and customs to an individual. This process continues along with socialization throughout the person’s lifetime. How the individual’s identity absorbs these shared societal principles varies depending on their interactions with other members of society and their willingness to self-identify with certain beliefs. For example, an individual who is raised among Christians and ultimately accepts the religion as a formative piece of their self would identify as a Christian. The same principle extrapolates in the context of politics and broader societal attitudes. Secondly, society bestows upon an individual a set of gender and associated occupational roles. Absorbing these roles into one’s identity begins during the second Eriksonian stage when the child begins to identify with (and often mimic) their parents’ manifestations of gender and profession. This progression continues throughout the adolescent and adulthood stages, as the individual accepts and rejects societal norms that surround gender behaviors and career choices. For example, a cisgender female may be brought up in a social circle where traditional gender roles are accepted, and wonder why these roles conflict with her desire to pursue a traditionally masculine profession. She may become more comfortable with her career choices upon being introduced to more progressive societal norms while attending educational institutions or entering the workplace. Thirdly, society plays a role in forming one’s sense of value and importance in a process that spans the childhood and adulthood Eriksonian stages. Children begin to form their perception of what is important in life by observing their caregivers and peers. Adolescents and young adults continue to develop their sense of value as they are exposed to the influence of society, including via media, friends, coworkers, romantic partners, and government messaging. For example, a young adult reaching maturity in a consumerist society may place great value on owning material goods and associate their identity with their possessions. Later in adulthood, overall dissatisfaction with life and societal trends such as the minimalist lifestyle may spur the individual to adjust their values, get rid of unnecessary possessions, and begin self-identifying as a minimalist. As the same adult reaches the generativity vs. stagnation stage, the realities of caring for children and ensuring their future success may force the person to return to an accumulation of wealth. The older adult may now identify as a provider and a caring parent.

Which personality type has an identity crisis?

There is no specific personality type that has an identity crisis in Eriksonian theory because the theory does not categorize people into personality types. Instead, Erikson’s theory aims to explain how various psychosocial conflicts shape a person’s identity throughout their lifespan. Erikson’s approach provides a more objective contrast to popular notions of personality types as having intrinsic properties of identity, such as the INFP Idealist being prone to identity crises in challenging times. An identity crisis is a developmental period that affects everyone progressing through the identity vs. role confusion conflict in the fifth Eriksonian development stage. An identity crisis is a period during which a teen experiments with different identities to find the one with which they’re most comfortable. The adolescent weighs the norms with which they were raised against those of their friends and the broader society. Childhood interests begin to fade as new ones take hold, while the desire to fit into a social circle may lead the youth to experiment with various aspects of their identity. The experimentation may manifest in physical and behavioral changes. The end of the identity crisis is marked by the youth’s acceptance of their newly found sense of self, or with confusion about who they are. These two opposing results of the identity crisis do not hinge on a personality type because the personality is undergoing development at this time. Instead, the outcome of an identity crisis depends on one’s interactions with family, friends, and society as a whole.

Is Erikson’s theory criticized?

Yes, Erikson’s theory is criticized, although the premise behind it is widely accepted in modern psychology and even clinical settings. Erikson’s theory has received the following two criticisms. Firstly, Erikson’s theory is criticized for asserting that development and psychosocial conflicts occur in a sequential order rather than at any point (or on multiple occasions) throughout the lifetime of an individual. Critics claim that the psychosocial conflicts described by Erik Erikson, and the development they cause, should not be limited to a specific time period of a person’s life. Erikson himself acknowledged this criticism, stating that he had arranged the conflicts in sequential order because that’s when they are most prominent. Secondly, Erikson’s theory has received criticism for not offering substantive guidance on how to navigate through and achieve successful outcomes in each of the psychosocial conflicts. Erikson formulated his theory of ego development largely on his observations as a psychoanalyst and researcher. Thus, the theory explains Erikson’s understanding of the innate mechanisms behind the development of a person. However, it does not go deep into explaining the experiences that shape each stage, or steps for resolving their associated psychosocial conflicts.