The Freud personality theory is a collection of principles that purport to explain human behavior. The Freud personality theory was formulated by Sigmund Freud in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and is considered the basis of modern psychology despite being partially disproven by modern scholars.

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the originator of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis is the clinical study of disorders that have no suspected biological cause, but rather stem from a disbalance of the psyche. Freud researched and developed psychoanalysis throughout his adult life, and his most prominent contribution to this field of study is his theory of personality.

Freud began developing his theory of personality while treating patients who were thought to be suffering from hysteria (an outdated term for excessively emotional and erratic behavior). Freud’s experience with his patients led him to believe that many behavioral symptoms had no discernable physiological cause. Conversely, Freud found that inducing catharsis in his patients often helped relieve unwanted behavioral symptoms. These findings galvanized Freud’s efforts to understand the links between one’s psyche, personality, and behavior.

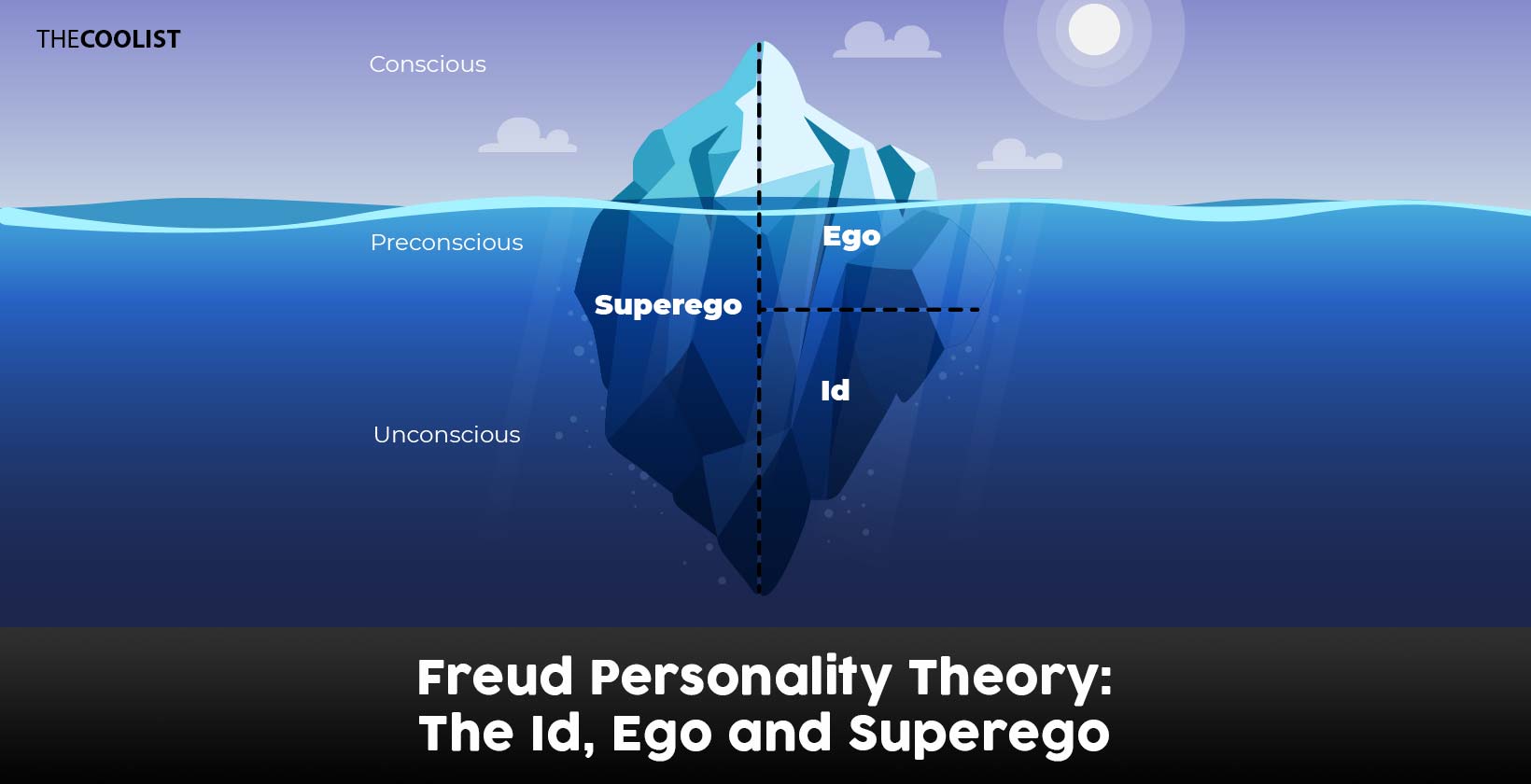

Freud’s first significant assertion was that the human mind is divided into conscious, preconscious, and unconscious parts. Freud believed that many of the pathologies exhibited by psychiatric patients stemmed from the unconscious. This notion led Freud to chart a topography of the mind, which depicted the three parts of the mind as an iceberg partially submerged in water.

Freud later came to believe that there was more to the mind than merely the different levels of consciousness. Thus, Freud came up with the three-part psychic apparatus, which comprised the Id, the Ego, and the Superego. Freud claimed that the interactions between these three components of the psyche shaped human behavior. A disbalance between the three parts led to neurosis or anxiety, to which the affected individual reacted via various defense mechanisms.

One of Freud’s most contentious assertions was that an individual’s personality and sexual behavior were shaped by the psychosexual development stages in their childhood and youth. Freud linked psychosexual development to the three parts of the psyche and claimed that issues during these development stages often manifested as psychological disorders in one’s adulthood.

Below is a thorough explanation of Freud’s theory of personality, including the Id, the Ego, the Superego, the various defense mechanisms, and the stages of psychosexual development.

What is the Id?

Id is the part of the unconscious that contains all the urges and impulses and operates according to the pleasure principle, according to Freud. The pleasure principle is the driving force behind our need for instant gratification. Id is present at birth and functions separately from the conscious mind and the rational thought the consciousness processes. Therefore, the primal impulses and desires contained within the Id are not subject to logic or reason. Often, the basal urges flowing from Id conflict or even cancel each other out, causing confusion and distress to the individual. The Id is additionally not subject to the individual’s value system. The Id does not differentiate between what we perceive as “good” or “bad”, “right” or “wrong”: The hard-wired impulses occur on an instinctual level. One has no means of stopping Id-based urges from manifesting despite comprehending their folly or rejecting them due to conflicts with one’s value system. All a person is able to do is control their actions despite the urges caused by the Id.

Freud’s theory of Id in personality states that the Id is the first part of the psyche to develop in an individual. People are born with intrinsic, instinctual urges that largely focus on the preservation and renewal of life. Over time, part of the Id develops into the Ego, which is one’s perception of self. The Ego operates according to the principle of reality, as the individual has at this point learned to factor the real world into their concept of self. The Id remains in an individual’s unconscious mind even as the Ego develops, so conducting a thorough analysis of one’s Id is a challenge. The only means of assessing one’s Id within the context of their psychic processes (known as the “psychic apparatus” in Freudian theory) is via the analysis of dreams and behavior caused by neurosis. An analysis of one’s Id is additionally only possible in relation to that person’s Ego, as such a comparison allows a psychologist to delineate instinctual urges (caused by the Id) from rationalized desires (caused by the Ego).

What are the examples of Id?

Examples of Id include urges caused by the intrinsic impulse to preserve and renew life, according to Freud. The first example of Id manifesting in a person’s behavior is their sexual drive. One’s sexual drive (also known as the libido) is rooted in the instinct to renew life via procreation, and sexual impulses occur despite any rational or conscientious barriers. Sexual urges may manifest as a direct impulse to engage in intercourse with someone or as a sexual fantasy. Freud believed that a person’s sexual urges are present at birth, along with the rest of the Id portion of the psychic apparatus. The second example of the Id influencing a person’s behavior is in hunger. A person’s biological need for sustenance pushes one to seek immediate satisfaction by indulging in a meal or snack. It takes a conscious effort led by the Ego to resist such urges when the person knows they are unhealthy. The third example of an impulse generated by the Id is aggressive behavior toward others and the self. Freud believed that the Id contained an intrinsic destructive instinct, which Freud called the “Death Drive” (referred to as “Thanatos” by psychoanalysts). According to Freud, the Death Drive stemmed from people’s inherent desire to return to an inorganic state (i.e. to die), which was generally kept in check by the more powerful urge to live. However, the Death Drive would often manifest itself outwardly as aggression toward others, or inwardly as self-harm or suicide. Other examples of Id revolve around individuals’ innate desires to acquire pleasure and material wealth. Such urges exist separately from rational thought or conscientiousness and have to be controlled by the Ego.

What is the Ego?

The Ego is the component of the personality that balances reality with the needs of the Superego and the Id, according to the Freudian theory. Freud’s reality principle is the notion that a person’s mind is able to observe and comprehend the world as it really is and base its actions on this understanding. The function of the Ego is to reconcile the untamed urges generated by the Id with reality through rational thought. The Ego is thus the nucleus of one’s perception and interpretation of the world and the control center that mediates between one’s primal urges and actual behavior.

Freud’s theory of Ego in personality describes it as an adjunct of the primal Id that mutates after exposure to the external world and exists both in the conscious and unconscious mind. The Ego is responsible for a person’s rational thought, which it uses constantly to maintain an equilibrium between the demands of reality, the impulses of the Id, and the constraints of the Superego. Maintaining this balance is often distressing to the individual, as the Ego simultaneously attempts to reconcile the dark and often impractical urges of the Id with the cold reality of the moment and the moral limitations imposed by the Superego. The Ego may compel the individual to exercise their willpower to repress an urge put forth by the Id, or to act in defiance of the moral norms dictated by the Superego in the name of practicality.

What are the examples of the Ego?

Examples of the Ego in Freudian theory include actions that balance the impulses produced by the Id, the norms imposed by the Superego, and the limitations of reality. One example of the Ego is the restraint of an Id-induced urge due to the impracticality and immorality its fulfillment entails. For example, an individual harboring a deep sexual attraction for a married person may repress the urge because of their Ego. The individual’s Ego comprehends that an affair with the married person is both impractical and immoral, thus leaning on both reality and the Superego to suppress the Id. However, the person might indulge in sexual fantasies about their object of desire to give Id an outlet, thus maintaining an equilibrium between reality, pleasure, and the three parts of the psychic apparatus. Such an indulgence may produce feelings of guilt stemming from the Superego, but the Ego keeps these misgivings in check because the sexual fantasies keep the Id satisfied without conflicting with reality or morality. Another example of the Ego is an individual’s refusal to obey social norms that clash with the reality of the moment. For example, a person swimming nude in a lake may run after a thief who stole their clothes from the shore, even though being unclothed in public contravenes established societal norms. In this case, the individual’s Ego identifies two realistic outcomes: Being nude in public briefly while pursuing the bandit, or going home without clothes, thus exacerbating the breach of morality. The Ego compels the person to undertake a task that conflicts with the Superego because it has a firm grasp on the reality of the moment. Thus, the nude swimmer gives chase to the thief.

What is the Superego?

The Superego in Freudian psychoanalytic theory is a component of the psychic apparatus that enforces cultural and societal norms, operating in one’s consciousness, preconsciousness, and subconsciousness. The Superego (which Freud initially termed the “ego ideal”) is thus the ethical component of an individual’s personality, or what many refer to as the “conscience.” A person’s Superego develops early in their infancy. Freud claimed that the Superego takes its roots in the ethos a child inherits from their parents’ Superegos, which allows a set of morals to pass down from one generation to another. The Superego absorbs norms from new role models and authority figures an individual encounters as they age.

According to Freud’s theory of superego in personality, the dominance of the Superego is dictated by the strength of the Oedipus complex before it dissipates. The Oedipus complex is a sexual desire experienced unconsciously by a child for the parent of the opposite sex. This desire teaches children to submit to authority, and the stronger the Oedipus complex before it recedes, the more dominant that child’s Superego becomes as they enter adulthood. A dominant Superego causes individuals to experience anxiety and exhibit neuroticism, as their Ego struggles to contain feelings of guilt and self-criticism. However, a well-balanced Superego helps the Ego maintain an equilibrium in response to the Id’s self-gratifying urges, which are often immoral and impractical.

What are the examples of the Superego?

Examples of the Superego include behaviors in which an individual’s moral compass steers them away from the darker urges of the Id or even suppresses rational decision-making. One example of the Superego is the repression of an urge instigated by the Id based on the individual’s adherence to social norms. For example, a person attending a corporate event may feel the urge to indulge in alcoholic beverages that are freely available. However, their Superego would keep this urge in check, as the person anticipates and fears the coworkers’ condemnation for breaching social norms and being inebriated in public. A second example of the Superego is an individual’s desire to perform a charitable deed even if it causes an inconvenience to them. For example, an individual’s Superego might compel them to volunteer for a cause they find worthy, even though they could spend the time performing self-serving tasks. A third example of the Superego is self-sacrificial behavior that stems from adherence to cultural or religious traditions. For example, practicing Christians and Muslims adhere to dietary restrictions during Lent and Ramadan, respectively. Such limitations often conflict with the biological and pleasure-seeking urges driven by the Id, but the individual’s Superego prevails and represses the Id. Allowing the Superego to prevail in this manner often causes the individual to feel gratification.

Which part of the psyche is related to the reality principle?

The Ego is the part of the psyche that’s related to the reality principle, according to Freud. The Ego is the component of the psyche apparatus that allows the individual to perceive and interpret the external world.

The realities of the surrounding world cause an individual’s Ego to adjust behaviors that are driven by impulses of the Id and the limitations of the Superego. The Id is a primal mechanism that generates impulses to satisfy the pleasure principle by providing instant gratification. The Id is disconnected from reality and is unable to adjust the urges it produces based on the constraints of the real world. Thus, it is up to the Ego to manage the impractical impulses produced by the Id and to correct the individual’s behavior accordingly. Allowing the Id to have the upper hand over reality and the Superego leads to psychotic behavior. Meanwhile, the Superego often conflicts with reality as it imposes acquired moral limitations on a person’s behavior. The Ego’s task involves finding a balance between the restrictions forced by the Superego and the real-world conditions. Allowing the Superego to outweigh reality and the Id leads to neurotic behavior. Ideally, the Ego must find an equilibrium between reality and the forces of the Id and Superego. This delicate balancing act manifests as a healthy psyche when successful.

How do these three parts of the psyche interact with each other and shape our personalities?

The three parts of the psyche interact with each other and shape our personalities by exerting their individual influences, which the Ego ultimately has to balance. Each of the three parts of the psychic apparatus serves a different function, and each part’s function determines how it interacts with the other components of the psyche. Below is an explanation of how each of the three components of the psyche interact with each other according to Freudian personality theory.

- Id: The Id is the unconscious part of the psychic apparatus that operates on the pleasure principle and does not directly interact with the two other parts of the psyche. The Id simply produces impulses dictated by the Life Drive (known as “Eros”) and Death Drive (known as “Thanatos”). These impulses are aimed at achieving gratification. Satisfying the Id gives an individual pleasure while repressing the Id makes the individual tense and uncomfortable. The Id does not evolve throughout a person’s lifetime, and, being deeply rooted in the unconscious mind, it has no awareness of reality or the two other parts of the psyche.

- Superego: The Superego operates both in the conscious and unconscious parts of the psyche, where it interacts with both the Ego and the Id. The Superego is the part of the Ego that absorbs cultural and societal norms and eventually manifests as an individual’s moral code. The Superego interacts with the Ego constantly, adding the concepts of “right” and “wrong” to the Ego’s balancing act between reality and intrinsic impulses. The Superego is additionally quick to repress the Id whenever the latter produces an urge that contravenes the individual’s internal code of ethics.

- Ego: The Ego functions within the conscious and subconscious components of a person’s psyche, and has ongoing interactions with both the Id and the Superego. The Ego is focused on gratification and pain avoidance but is grounded in reality, unlike the Id. As the Ego interprets impulses transmitted by the Id, it automatically accounts for the actuality of the moment, thus deciding on the most practical approach to fulfill the Id’s urges. The Ego declines the Id’s whims if it calculates the probability of their execution to be woefully low because of real-world circumstances. The Ego additionally engages with the Superego, as the latter imposes its limitations on the Ego’s balancing act between pleasure and reality. A healthy psyche exhibits a powerful Ego that’s able to juggle the pressures of the Id, the Superego, and the real-life circumstances. In an unhealthy psyche, the Ego is unable to manage the equilibrium between the Id and the Superego, and one of the two latter parts of the psychic apparatus becomes the dominant force in a person’s behavior.

Freud asserted that an inability to balance the interactions between the Id, the Ego, and the Superego harmoniously leads to psychiatric disorders. A disbalance between the three psyche parts causes the individual to feel anxious and harms their self-image and self-esteem. The need to relieve this anxiety and safeguard self-esteem and self-image leads to the deployment of various self-defense mechanisms by the individual. The table below describes eight defense mechanisms identified by Sigmund Freud.

| Defense Mechanism | Definition | Example of behavior |

| Repression | Driving unacceptable thoughts from the conscious into the unconscious mind. | Inability to recall a traumatic event that had occurred in one’s childhood. |

| Regression | Regressing the Ego to an earlier, less advanced stage of development instead of adapting it to handle objectionable urges. | Uncontrollable crying and tantrums in response to anxiety or frustration. |

| Reaction formation | Overcoming an unacceptable impulse by forcefully channeling it into the opposing tendency. | Behaving cold and aloof around someone for whom the individual experiences unwanted sexual urges. |

| Isolation | Separating unwanted thoughts or emotions from the rest of the individual’s thoughts. | Making a mental gap after experiencing an unpleasant emotion before continuing the train of thought. |

| Projection | Defending against unwanted urges, thoughts, or behaviors by attributing them to other people. | Accusing a partner of causing relationship issues that the accuser in fact caused themselves. |

| Introjection | Absorbing the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of another person in situations that cause anxiety. Introjection contributes to the construction of the Superego. | A child adopts the beliefs or behavioral patterns of their parents. |

| Sublimation | Channeling unacceptable or negative impulses into positive, productive behaviors. | A person experiencing unrequited romantic feelings channeling their emotions into art. |

| Displacement | Ego substituting the impulse (or the object of the impulse) deemed unacceptable for a new one. | A worker who’s upset with their supervisor taking out anger on their spouse because doing so does not present a danger to their career. |

How did Sigmund Freud develop his personality theory?

Sigmund Freud developed his personality theory by seeking out links between patients’ symptoms of hysteria and their psyche. In the late 1880s, Freud worked with French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who had been attempting to find a root cause behind hysteria, an outdated umbrella diagnosis describing excessively emotional, erratic behavior. Freud and Charcot interviewed a number of women with symptoms of various physiological and psychological disorders (classified as hysteria at the time), and established that these symptoms had no biological root cause. However, Freud and Charcot had observed that women exhibiting signs of “hysteria” often had repressed childhood trauma, which they would recount under hypnosis. Many of the patients underwent a catharsis during their hypnotic sessions with Freud and Charcot, and this sudden eruption of pent-up emotions and hidden memories caused their symptoms to subside afterward. This link between the latent parts of an individual’s psyche and their behavioral patterns led Sigmund Freud to develop his personality theory.

The first discovery in Sigmund Freud‘s long path to formulating his personality theory was that much of human behavior stems from the unconscious mind. The behavioral influence of the hidden part of the psyche was a revolutionary idea at the time, as Freud’s contemporaries had no rational explanations for the source of human behavior. Freud’s ideation on the topography of the human mind led him to identify the following three parts, which are often referred to as the “Iceberg Theory.”

- Consciousness: The conscious part of the mind is responsible for processing the mental activities of which we are aware. This part of the mind comprises thoughts and perceptions. The consciousness represents the tip of the iceberg in Freud’s topography.

- Preconsciousness: Freud described preconsciousness as the “mental waiting room”: A part of the mind that stores memories and knowledge for easy access by the consciousness. The preconsciousness occupies the portion of the iceberg immediately beneath the water line, according to Freud.

- Unconsciousness: The unconsciousness is the part of the mind of which we’re unaware. Unconsciousness conceals our intrinsic, instinctual urges, dark motivations, and repressed thoughts and memories. We are unable to access this part of the mind, which consequently comprises the lowest, deepest portion of Freud’s iceberg depiction.

Further studies and research led Freud to believe that there was more to the human psyche than the three levels of consciousness. Thus emerged Freud’s psychic apparatus comprising the Id, the Ego, and the Superego. According to Freud, the Id is responsible for a person’s basal impulses, driven by the life and death instincts, and resides in the unconscious mind. The Superego is the learned foundation of an individual ethical code, and it spans the entire height of the iceberg, with parts in the unconscious, preconscious, and conscious minds. Meanwhile, the Ego is the arbiter that reconciles the needs of the Id and the Superego with real-world situations. The Ego exists in the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious portions of the mind.

Freud expanded his personality theory further by attributing the molding of one’s psyche and sexuality to certain phases of one’s childhood. Below are the five stages of Freudian psychosexual development.

- Oral: The oral stage lasts from birth until approximately 18 months and is characterized by sucking, chewing, and biting. Exploring objects with the mouth gives the child pleasure. Unmet needs during the oral stage lead to oral fixation (behaviors such as nail biting and smoking) according to Freud.

- Anal: The anal stage begins at 18 months and lasts through the child’s third birthday. Children at this age experience pleasure from emptying the bowels. According to Freud, strict potty training causes anal-retentiveness in adulthood, a behavior pattern that exhibits obsession with detail and fussiness. Conversely, Freud believed that adults who underwent excessively passive potty training as children become anal-expulsive, a trait characterized by rebelliousness and disorganization.

- Phallic: The phallic stage occurs in children between 3 and 6 years of age and entails receiving pleasure from the genitals. The phallic stage sees the child develop a sexual fixation on their parent of the opposite sex (known as the “Oedipus complex” for male and “Electra complex” for female children). Freud believed that the more intense this sexual fixation is, the greater the hold of the person’s Superego in adulthood. Toward the end of the phallic stage, the child relinquishes their love for the opposite-sex parent and starts idealizing the parent of the same sex.

- Latency stage: The latency stage begins around the time of the child’s sixth birthday and lasts until they turn twelve. Latency is a calm stage in the child’s psychosexual development, during which sexual impulses are largely repressed.

- Genital stage: The beginning of the genital stage at 12 years ushers in the age of psychosexual maturity and lasts as the individual progresses into adulthood.

Freud continued refining the various aspects of his personality theory until his death. Freud’s understanding of the Id, Ego, and Superego have been partly discredited by modern psychologists. Additionally, the five stages of psychosexual development in Freudian theory have been widely criticized for their perceived sexist attitudes toward women. However, Freud’s contribution to modern psychology has been fundamental, and many of the concepts he developed continue to shape psychology to this day.

Which part of the mind creates selfish impulses?

The part of the mind that creates selfish impulses is the Id, according to Freudian theory. The Id is the unconscious component of one’s psychic apparatus that’s not subject to the constraints of morality or reality. The Id’s sole purpose is to generate impulses that lead to instant gratification for the individual. The basis of the Id’s urges lies in the person’s intrinsic life and death drives. The life drive is a person’s instinctual motivation to maintain and preserve their biological processes and renew life via procreation. The life drive accounts for the person’s libido, as well as their urges to satisfy biological needs such as hunger and thirst. The death drive represents a person’s innate desire to return to an inorganic state, according to Freud. The death drive causes Id to produce destructive impulses, such as aggression against others or acts of self-harm. Both the life and death drives result in impulses that are entirely selfish, as their purpose serves only the individual. People are unable to stop the Id from generating self-serving urges, but they’re able to manage them with their Ego and Superego, the other two parts of the psychic apparatus.

Which part of the mind is responsible for our behaviors?

All three parts of the mind are responsible for our behaviors. The Id, the Superego, and the Ego all play a role in shaping the personality and behavior of an individual. The Id produces urges aimed at providing immediate satisfaction to the individual, and these urges are rooted in the innate motivation for survival and destruction. The Superego serves as the person’s moral compass, making one view their desires, thoughts, and behaviors through an ethical lens. The Ego balances the impulses of the Id and the impositions of the Superego with the realities of the circumstances at hand. The interaction between the Id, the Superego, and the Ego is responsible for our behaviors according to Freudian theory. That said, any one of the three psyche parts could be the dominant force behind one’s behavior. According to Freud, the dominance of the Id or Superego leads to anxiety and neuroticism, respectively. Meanwhile, the dominance of the adjudicating Ego leads to healthy, balanced behavior patterns that exhibit an equilibrium between selfish motivations, morality, and reality.

How does the Superego differ from the Id and the Ego?

The Superego differs from the Id and the Ego in two ways. Firstly, the Superego differs from the Id and the Ego as it operates on a different principle than the two other psyche parts. The Id functions according to the pleasure principle, pushing the individual to seek immediate satisfaction. The Ego operates based on the reality principle, as it factors in the present circumstances into the individual’s behavior. Meanwhile, neither pleasure nor reality are relevant to the Superego, which instead functions according to the morality principle. According to Freud, the Superego contains and enforces the ethical standards that the individual has internalized during their psychological development. The Superego thus acts as one’s moral compass regardless of all real-life circumstances and notwithstanding one’s innate urges. Secondly, the Superego differs from the Id and the Ego as its nature is internalized and largely dependent on external factors, which is not the case for the Id and the Ego. The Id is present at birth, according to Freudian theory, while the Ego develops quickly as a child develops agency but before they absorb influences from their surrounding environment. In contrast, the Superego develops in response to the child’s external circumstances and is largely influenced by the authority figures in one’s childhood and youth. This importance of external influence in molding one’s Superego means that this part of the psyche varies greatly between all persons, whereas the Id and the Ego are more universal.

What is the difference between the Id and the Ego?

There are four differences between the Id and the Ego. Firstly, the Id exists entirely in an individual’s unconscious mind, whereas the Ego operates in the unconscious, preconscious, and conscious minds. This distinction means that a person is unaware of their Id and is unable to influence which urges it generates. The Id is completely unaffected by the thoughts or feelings of a person, which may well conflict with the impulses it generates. Conversely, a person is aware of their Ego and its attempts to balance reality with pleasure, as this balancing act happens on a conscious level. Secondly, the Id differs from the Ego in the principle upon which it operates. The Id functions on the pleasure principle, sending impulses that would lead to instant gratification for the individual. On the other hand, the Ego works according to the reality principle, taking its cues from the actuality of the moment and understanding the consequences of behavior. The Ego still strives to achieve pleasure, but reconciles this drive for satisfaction with real-world conditions. Thirdly, the Id differs from the Ego in the stage of development at which it emerges. The Id is present at birth while the Ego emerges as the child learns to comport themselves. Finally, the Id differs from the Ego because it does not change throughout a person’s lifetime, while the Ego does. The Id remains a primal motivational force responsible for various impulses from one’s birth until their death. An individual is able to control these impulses with their Ego. This ability to interpret, counteract, and otherwise manage Id’s urges may change throughout a person’s lifetime as the Ego evolves.

Is the Id the same as the subconscious?

No, the Id is not the same as the subconscious. The Id is a part of the psychic apparatus that produces basic, instinctual urges and exists in a person’s unconscious mind. The term “subconscious” describes the part of the human mind that operates outside the focal point of awareness. Both the Id and the subconscious mind influence an individual’s behavior, but they do so differently. Below is a breakdown of how the Id and the subconscious mind affect behavior.

- The Id: The Id generates impulses that are rooted in a person’s drive to live or die, and are aimed at affording the individual immediate satisfaction. For example, the Id fuels a person’s sexual desire when they find someone else attractive.

- The subconscious mind: The subconscious mind stores skills and knowledge for easy retrieval when needed. Thus, the subconscious is able to help direct a number of bodily functions and behaviors without requiring the individual’s attention. For example, the subconscious mind controls one’s breathing and the blinking of one’s eyelids and helps a person steer the wheel as they drive.

Can we see the effects of these three parts of the mind in our everyday lives?

Yes, we can see the effects of these three parts of the mind in our everyday lives, according to the Freudian personality theory. Freud believed that the interactions between the Id, the Ego, and the Superego were ultimately responsible for all observable and latent human behavior. Any interaction between the three parts of the psyche could result in a person’s perceivable actions. For example, a desire to satisfy one’s appetite by consuming food is attributable to the Id, whereas the subsequent action of either proceeding to eat or not is decided by the Ego, with or without the input of the Superego. Thus, a person buying and eating a hot dog on the street exhibits an interaction of the three parts of the psyche in Freudian theory.

However, the validity and credibility of Freud’s personality theory have been partially disproven by modern psychology, as the theory lacks empirical evidence. Whether the Id, the Ego, and the Superego cause observable effects in our everyday lives (and whether they exist at all) remains a question as psychology continues to evolve.